Android Programming: Pushing the Limits (2014)

Part III. Pushing the Limits

Chapter 15. The Hidden Android APIs

Android developers know that tons of features in the platform aren’t accessible through the official and public

APIs. For instance, although Android has classes for sending SMS (SmsManager and SmsMessage), there is no

official API for receiving them. Nevertheless, you can find several applications on the Google Play Store site that

provide full-featured SMS clients, and many apps are built around incoming SMS. Although a simple Google

search will give the necessary information for how to receive SMS in an Android application, you’ll come upon

many other cases where the hidden platform APIs in Android could be useful in applications.

In this chapter, I explain how and where to find hidden APIs. I also describe different methods for accessing

them and how to do so in a safe and secure way.

Most of the hidden Android APIs are also protected by permissions that have a protectionLevel of

signature or system (refer to Chapter 12). Although you can’t use these APIs in regular applications you

publish on the Google Play Store, you can still use them in applications you write for a custom firmware. Doing

so allows you to access these APIs without changing the Android platform. (See Chapter 16 for more on how to

build a custom firmware.)

Official and Hidden APIs

The official APIs are all the classes, interfaces, methods, and constants found in the SDK documentation.

Although these APIs are usually enough for most applications, at times you’ll want to access something more,

but don’t know how to find them in the official APIs.

When Google publishes the Android SDK, it contains a JAR file (android.jar) that you use as a reference

when compiling your code. You can find this file via <sdk root>/platforms/android-<API level>/.

The file contains only empty classes, meaning that it includes only the public and protected declarations and all

code within the methods has been scrubbed away. This JAR file is generated as part of the SDK when you build

the platform.

The scrubbed android.jar file is generated when the SDK is built by inspecting each source file and

excluding every field (such as constants), method, and class with the JavaDoc annotation @hide (see Figure 15-1).

This means that these symbols are still accessible to the implementation running on the device but they aren’t

visible at compile time.

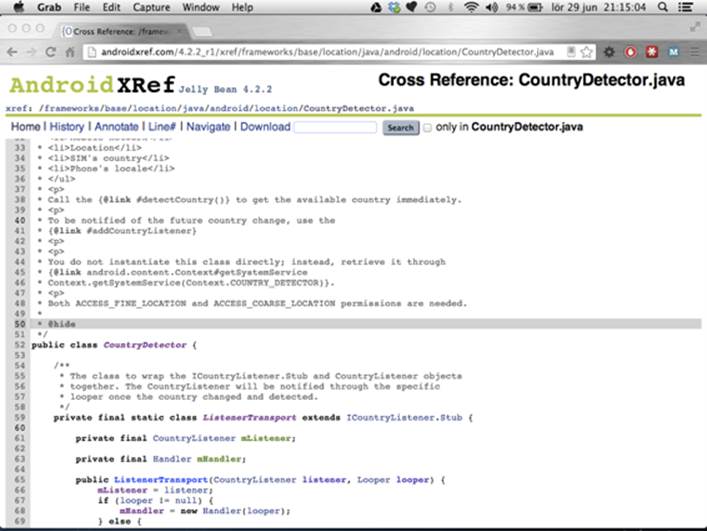

Figure 15-1 The source code for the hidden class CountryDetector . Note the @hide annotation for the JavaDoc .

Some APIs in Android are hidden automatically, without the @hide annotation. You can usually find these APIs

in the package com.android.internal, which is never part of the android.jar but does contain lots of

code for internal use in Android. You can find some of the other hidden APIs in the system applications. These APIs

usually have ContentProvider information for the system providers that isn’t included in the official SDK.

Discovering Hidden APIs

The easiest way to find the hidden APIs is to search for them in the Android source code. The source code for the

Android platform is vast, but fortunately several online sites have indexed the code and made it searchable. One

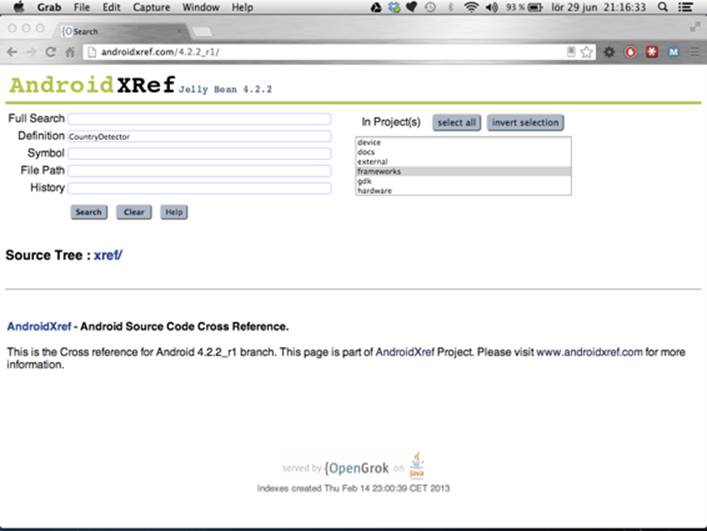

such site is AndroidXRef (http://androidxref.com), which allows you to search all the open source code

for all officially released Android versions (see Figure 15-2).

Figure 15-2 The Search dialog box at AndroidXRef

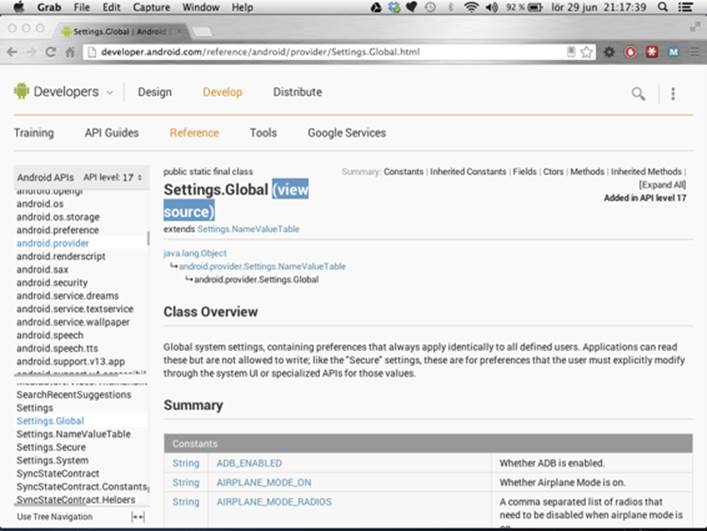

Another way to look for hidden APIs is through the View Source link on the Android API reference site (see

Figure 15-3). This site doesn’t provide a search method like AndroidXRef does, but it’s easier to access directly

from the official API documentation.

Although searching is good if you know where and what to look for, finding the code that does what you need

can be difficult. You can find most of the hidden APIs in the frameworks project. All of the APIs in the android

package can be found here as well as most of the APIs in com.android.internal.

Often the hidden API you’re looking for is part of a class that is public. For instance, the WifiManager has

several public, unhidden, methods but also a number of useful hidden methods and fields. In other cases, the

class is hidden from the public API, such as the CountryDetector class shown earlier in Figure 15-1.

Figure 15-3 The View Source link for Settings .Global on the API reference site

Safely Calling Hidden APIs

Constant fields, such as broadcast actions or provider Uri, are major parts of the useful hidden APIs. You can

copy these fields into your own code and use them just as they are. The easiest way to do so is to copy the

entire class (for instance, directly from AndroidXRef) and place it in your project. If these hidden APIs have been

changed in the different Android API levels, you can keep a copy of each version in its own package. This way,

you can use a hidden API and still target multiple Android versions.

For most situations in which you need to use a hidden API that consists of constants (such as

broadcast actions), I recommend copying the hidden constants from the Android source code.

For APIs that require compile-time linking—that is, interfaces, classes, and methods—you have two choices. You

can compile your application with a modified SDK that contains a JAR file with all the classes and interfaces you

need. The other solution is to use the Reflection API in Java to dynamically look up the classes and methods you

want to call. Each method has its pros and cons, and your choice will depend on the situation.

Modifying the SDK will effectively bind your code to the device you use when generating the modified

android.jar (see the section “Extracting Hidden APIs from Device”) and could result in your code crashing

on other devices if you’re not careful. However, there’s no performance penalty with this solution. Using the

Reflections API allows you to target multiple Android versions but can penalize performance because it requires

a runtime lookup of classes and methods. I discuss both these approaches in the following sections.

Extracting Hidden APIs from a Device

To do compile-time linking to the hidden APIs, you first need to extract and process the libraries from a device.

You can extract these libraries either from an emulator instance or from a device because they’ll be used only

for compiling your code. Because this work requires a number of files from a device, I recommend that you

create an empty working directory. Since you may want to perform this task for multiple API versions, you can

create one working directory per API level.

$ adb pull /system/framework .

pull: building file list...

pull: <files pulled from device>

63 files pulled. 0 files skipped.

4084 KB/s (35028810 bytes in 8.374s)

Run the preceding command from your working directory, and you’ll see that it pulls all the files from the

directory /system/framework on the device. Once the extraction is completed, you can list the files, and the

output should look somewhat like the following (it may vary depending on the device’s manufacturer and the

version of Android you’re using):

$ ls

am.jar ext.jar

am.odex ext.odex

android.policy.jar framework-res.apk

android.policy.odex framework.jar

android.test.runner.jar framework.odex

android.test.runner.odex ime.jar

apache-xml.jar ime.odex

apache-xml.odex input.jar

bmgr.jar input.odex

bmgr.odex javax.obex.jar

bouncycastle.jar javax.obex.odex

bouncycastle.odex mms-common.jar

bu.jar mms-common.odex

bu.odex monkey.jar

com.android.future.usb.accessory.jar monkey.odex

com.android.future.usb.accessory.odex pm.jar

com.android.location.provider.jar pm.odex

com.android.location.provider.odex requestsync.jar

com.android.nfc_extras.jar requestsync.odex

com.android.nfc_extras.odex send_bug.jar

com.google.android.maps.jar send_bug.odex

com.google.android.maps.odex services.jar

com.google.android.media.effects.jar services.odex

com.google.android.media.effects.odex settings.jar

com.google.widevine.software.drm.jar settings.odex

com.google.widevine.software.drm.odex svc.jar

content.jar svc.odex

content.odex telephony-common.jar

core-junit.jar telephony-common.odex

core-junit.odex uiautomator.jar

core.jar uiautomator.odex

core.odex

These files are all the Java-based system libraries on your Android device. They are the optimized DEX files that

are loaded by the Dalvik VM. The next step is to decide which file contains the hidden APIs you want to convert

back to Java class files that you can use when compiling your application. Most of the hidden APIs are placed in

framework.odex, whereas the crypto-libraries are in the bouncycastle.odex file.

Starting with Android 4.2, several hidden APIs that used to be in framework.odex are now placed

in other files. For instance, the hidden Telephony class is now optional (because not all Android

devices have telephony support) and can now be found in telephony-common.odex.

Once you know which file you need to convert, you download a tool named Smali that can convert the

optimized DEX files (.odex) to an intermediate format (.smali). You can then convert this intermediate

format back to Java class files using another tool named dex2Jar. You can download Smali at https://

code.google.com/p/smali, and you can find dex2Jar at https://code.google.com/p/dex2jar.

Download both and extract them to an appropriate location (for instance, next to your working directory). Start

by converting the ODEX file to the intermediate format as shown here:

$ mkdir android-apis-17

$ java -jar ~/Downloads/baksmali-2.0b5.jar -a 17 -x framework.odex -d . -o

android-apis-17

When you run this command from the same directory where you pulled the files from the device, the file

framework.odex is converted to a number of SMALI files placed in the correct package structure in the

directory android-apis-17. Next, you need to convert these files into a single DEX file.

$ java -jar ~/Downloads/smali-2.0b5.jar -a 17 -o android-apis-17.dex

android-apis-17

You can repeat the two preceding steps for each file you need to convert. For instance, on Android 4.2, the

hidden Telephony class is placed in telephony-common.odex. This way, you can create a single JAR file in

the end with all the hidden classes you need, even if they’re contained in different ODEX files from the start.

Finally, you need to use the dex2Jar tool to convert the DEX file into a JAR file containing all the Java class files.

$ ~/Downloads/dex2jar-0.0.9.15/d2j-dex2jar.sh android-apis-17.dex

dex2jar android-apis-17.dex -> android-apis-17-dex2jar.jar

The resulting JAR file contains all the classes, both hidden and public, from the original ODEX file (or files). To

use this file instead of the default android.jar in your SDK, simply rename it to android.jar and replace

it with the one in your SDK (for instance, <sdk root>/platforms/android-17/android.jar).

Remember to back up the original file in case you want to revert to the original SDK without the hidden APIs.

This approach provides you with a set of platform APIs that are guaranteed to work only on the device

you extracted the files from. Because this is the baseline for all other Android devices, I recommend

doing this only from a Nexus device with an official factory image. Perform this only on a non-Nexus

device if you need to use the hidden, proprietary APIs implemented by the device’s manufacturer (for

instance, a hidden camera extension API or something similar).

Error Handling for Modified SDK

When utilizing the approach for using the hidden APIs described previously, it’s difficult to know whether the

method signatures from your extracted classes match the ones that users have on their devices. Although

modifying the SDK may work on the device you use for development, a user who installs your application may

have a device where the hidden APIs are modified by the vendor. When that happens, your application will

throw a NoSuchMethodException or ClassNotFoundException.

You can deal with this situation a couple of ways. You can combine this approach with the use of reflections

(described in the next section) to detect the presence of your hidden APIs. In this way, you have the benefit of

both solutions, which I recommend. Another way is to simply catch the exception so that you can perform some

graceful degradation of the functionality.

Whatever you do, be sure to perform some error handling when calling hidden APIs. At the very least, you can

limit the availability of your application to the devices you’ve tested on. You always want to avoid having your

application crashing on a user’s device.

Calling Hidden APIs Using Reflections

The Reflections API in Java (found in the java.lang.reflect package) gives you a safer approach than

modifying the SDK does because you can use it to detect the presence of an API (or lack thereof) before calling

it. However, because all binding and invocation of hidden APIs occur in runtime, this method is also slower than

the alternative method described in the previous section.

Calling a hidden API using Reflections is a two-step process. First, you need to look up the class and methods

you want to call and store a reference to the Method object. After you have this reference, you can invoke

the method on an object. The two steps are shown in the following code, where you look up the method for

checking the state of Wi-Fi tethering:

public Method getWifiAPMethod(WifiManager wifiManager) {

try {

Class clazz = wifiManager.getClass();

return clazz.getMethod(“isWifiApEnabled”);

} catch (NoSuchMethodException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}

public boolean invokeIsWifiAPEnabled(WifiManager wifiManager,

Method isWifiApEnabledMethod) {

try {

return (Boolean) isWifiApEnabledMethod.invoke(wifiManager);

} catch (IllegalAccessException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

} catch (InvocationTargetException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}

The preceding example shows a fairly simple invocation using the Reflections API. If the hidden method

takes parameters, you need to provide the classes for those in the call to Class.getMethod(). Also, in this

example, the only error handling is to throw a RuntimeException. In your own application, you should

handle errors properly and do a graceful degradation of your application’s feature set.

Never assume that methods you retrieve using Reflections are available on all devices. If they’re hidden, the

manufacturer may have modified them and changed their signature (number of parameters, for instance).

In the early days of Android, this situation was quite common because many features were missing in the

platforms added by manufacturers. However, now you can usually expect the API to be there, just take care to

do proper error handing and feature fallback when using the hidden APIs.

Examples of Hidden APIs

In this section, I show a few examples of how hidden APIs are used. These are some of the typical scenarios I’ve

discovered that developers are asking for.

Receiving and Reading SMS

The most commonly requested hidden API in Android is related to receiving and reading SMS. Although the

public API contains two permissions, RECEIVE_SMS and READ_SMS, the actual API for performing these

actions is hidden.

An application that must be able to receive an SMS must declare the use of the RECEIVE_SMS permission and

implement a BroadcastReceiver that is triggered for incoming SMS.

public class MySmsReceiver extends BroadcastReceiver {

// Hidden constant from Telephony.java

public static final String SMS_RECEIVED_ACTION

= “android.provider.Telephony.SMS_RECEIVED”;

public static final String MESSAGE_SERVICE_NUMBER = “+461234567890”;

private static final String MESSAGE_SERVICE_PREFIX = “MYSERVICE”;

public void onReceive(Context context, Intent intent) {

String action = intent.getAction();

if (SMS_RECEIVED_ACTION.equals(action)) {

// “pdus” is the hidden key for the SMS data

Object[] messages =

(Object[]) intent.getSerializableExtra(“pdus”);

for (Object message : messages) {

byte[] messageData = (byte[]) message;

SmsMessage smsMessage =

SmsMessage.createFromPdu(messageData);

processSms(smsMessage);

}

}

}

private void processSms(SmsMessage smsMessage) {

String from = smsMessage.getOriginatingAddress();

if (MESSAGE_SERVICE_NUMBER.equals(from)) {

String messageBody = smsMessage.getMessageBody();

if (messageBody.startsWith(MESSAGE_SERVICE_PREFIX)) {

// TODO: Message verified - start processing...

}

}

}

}

The preceding code shows a BroadcastReceiver that listens for the Intent action android.provider.

Telephony.SMS_RECEIVED (remember to add this to the intent-filter in the manifest as well). The

only “hidden” parts in this example are this Intent action and the String to retrieve SMS data from the

Intent (“pdus”).

For reading already received SMS, you need to query a hidden ContentProvider and declare the use of the

permission READ_SMS. The hidden class Telephony, found in the android.provider package, provides

all of the information needed. The best way to use this class is to simply copy it to your own projects and refactor

it to suit your package structure. Because it also contains calls to other hidden classes and methods, you must

either remove or refactor these calls to make your code compile. Depending on how much of this hidden API

you’ll need to use, sometimes it’s enough to simply copy a number of constant declarations instead of the

entire class.

@Override

public void onActivityCreated(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onActivityCreated(savedInstanceState);

mAdapter = new SimpleCursorAdapter(this,

R.layout.sms_list_item, null,

new String[] {Telephony.Sms.ADDRESS, Telephony.Sms.BODY,

Telephony.Sms.DATE},

new int[] {R.id.sms_from, R.id.sms_body, R.id.sms_received},

CursorAdapter.FLAG_REGISTER_CONTENT_OBSERVER);

setListAdapter(mAdapter);

getLoaderManager().initLoader(0, null, this);

}

public Loader<Cursor> onCreateLoader(int id, Bundle args) {

Uri smsUri = Telephony.Sms.CONTENT_URI;

return new CursorLoader(getActivity(), smsUri, new String[] {

Telephony.Sms._ID,

Telephony.Sms.ADDRESS,

Telephony.Sms.BODY,

Telephony.Sms.DATE},

null, null, Telephony.Sms.DEFAULT_SORT_ORDER);

}

Here are two methods shown from a custom ListFragment, which loads a Cursor from the Content

Provider for SMS and loads that into a SimpleCursorAdapter. The Uri for the provider and the name

of the columns are all the content used from the Telephony class.

Wi-Fi Tethering

Android smartphones can enable Wi-Fi tethering, which makes it possible to create a mobile Wi-Fi hotspot that

allows other devices (usually your laptop) to connect to the Internet when you’re traveling. This feature is a very

popular one on Android, but it has caused some problems for application developers.

When the user enables Wi-Fi tethering, the state of the Wi-Fi is neither on nor off, but “unknown” if you query it

through the public API. In a previous example (see the “Calling Hidden APIs Using Reflections” section), I showed

how to detect whether Wi-Fi tethering is enabled using hidden method isWifiApEnabled(). A number of

other hidden methods in the WifiManager class provide you with more information about Wi-Fi tethering.

private WifiConfiguration getWifiApConfig() {

WifiConfiguration wifiConfiguration = null;

try {

WifiManager wifiManager =

(WifiManager) getSystemService(WIFI_SERVICE);

Class clazz = WifiManager.class;

Method getWifiApConfigurationMethod =

clazz.getMethod(“getWifiApConfiguration”);

return (WifiConfiguration)

getWifiApConfigurationMethod.invoke(wifiManager);

} catch (NoSuchMethodException e) {

Log.e(TAG, “Cannot find method”, e);

} catch (IllegalAccessException e) {

Log.e(TAG, “Cannot call method”, e);

} catch (InvocationTargetException e) {

Log.e(TAG, “Cannot call method”, e);

}

return wifiConfiguration;

}

The preceding code shows how you can retrieve the WifiConfiguration for the Wi-Fi tethering settings

on a device. Note that calling these methods requires that your application have the permission android.

permission.ACCESS_WIFI_STATE. All Wi-Fi networks that an Android device has configured (that is,

connected to) can be enumerated as a list of WifiConfiguration objects through the WifiManager.

getConfiguredNetworks(). In each of the WifiConfiguration objects retrieved through this

method, the preSharedKey is set to null for obvious security reasons. However, when retrieving the

WifiConfiguration object for the Wi-Fi tethering settings as shown in the preceding code, you’ll find the

clear-text password present in the preSharedKey variable. In this way, your application can retrieve both the

name for the access point that is created when you activate Wi-Fi tethering and the password.

Although this feature can be considered a security flaw, it’s good to know that the permission needed to

activate Wi-Fi tethering requires your application to be signed with the system certificate. Thus, even if an

application can read the password, there’s no way for it to activate Wi-Fi tethering without the user’s consent.

Hidden Settings

An Android device has hundreds of different settings that are available through the class Settings. Besides

providing access to the value for each setting, it publishes a number of Intent actions that you can use

to launch a specific part of the settings UI. For instance, to launch the settings for airplane mode, you use

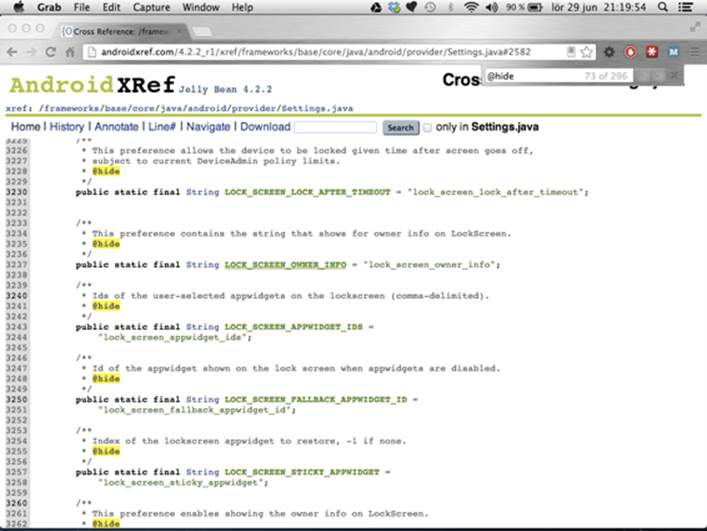

Settings.ACTION_AIRPLANE_MODE_SETTINGS when creating the Intent. Figure 15-4 shows how the

file Settings.java looks like when viewed through AndroidXRef.

Figure 15-4 Some of the hidden constants in the source file Settings.java

A number of hidden setting keys and Intent actions are in the Settings class, some of which can be very

useful when your application needs to figure out details about the device or when you want to present a

shortcut within your application to a certain system setting.

Summary

This chapter introduced how you can discover and use the hidden APIs in the Android platform. Although only

a few examples are shown, the number of available hidden APIs is quite large. Most of these APIs are not only

hidden but also protected with permissions with the signature or system protection level, which makes

them unusable for most Android developers. However, as you will see in the next chapter, they can be an

efficient method for building advanced applications with access to system APIs if you build them for a device

with a custom firmware.

Some of the APIs are simple constants used to access ContentProviders, Intent actions for launching

Activities or settings keys for reading hidden system settings, whereas others are methods that you need

to invoke.

Although most applications will never require these APIs, in some situations, you’ll benefit by using an API that

is officially unavailable. Using the hidden APIs in a smart way will allow you to further enhance your apps.

Further Resources Websites

An index of all the Android source code sorted according to specific versions: http://androidxref.com

The Java tutorials on the Reflection API: http://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/reflect

The utility for converting ODEX files to DEX format: https://code.google.com/p/smali

The utility for converting DEX files to JAR files with Java classes: https://code.google.com/p/dex2jar

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2026 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.