Learning Python (2013)

Part VI. Classes and OOP

Chapter 26. OOP: The Big Picture

So far in this book, we’ve been using the term “object” generically. Really, the code written up to this point has been object-based—we’ve passed objects around our scripts, used them in expressions, called their methods, and so on. For our code to qualify as being truly object-oriented (OO), though, our objects will generally need to also participate in something called an inheritance hierarchy.

This chapter begins our exploration of the Python class—a coding structure and device used to implement new kinds of objects in Python that support inheritance. Classes are Python’s main object-oriented programming (OOP) tool, so we’ll also look at OOP basics along the way in this part of the book. OOP offers a different and often more effective way of programming, in which we factor code to minimize redundancy, and write new programs by customizing existing code instead of changing it in place.

In Python, classes are created with a new statement: the class. As you’ll see, the objects defined with classes can look a lot like the built-in types we studied earlier in the book. In fact, classes really just apply and extend the ideas we’ve already covered; roughly, they are packages of functions that use and process built-in object types. Classes, though, are designed to create and manage new objects, and support inheritance—a mechanism of code customization and reuse above and beyond anything we’ve seen so far.

One note up front: in Python, OOP is entirely optional, and you don’t need to use classes just to get started. You can get plenty of work done with simpler constructs such as functions, or even simple top-level script code. Because using classes well requires some up-front planning, they tend to be of more interest to people who work in strategic mode (doing long-term product development) than to people who work in tactical mode (where time is in very short supply).

Still, as you’ll see in this part of the book, classes turn out to be one of the most useful tools Python provides. When used well, classes can actually cut development time radically. They’re also employed in popular Python tools like the tkinter GUI API, so most Python programmers will usually find at least a working knowledge of class basics helpful.

Why Use Classes?

Remember when I told you that programs “do things with stuff” in Chapter 4 and Chapter 10? In simple terms, classes are just a way to define new sorts of stuff, reflecting real objects in a program’s domain. For instance, suppose we decide to implement that hypothetical pizza-making robot we used as an example in Chapter 16. If we implement it using classes, we can model more of its real-world structure and relationships. Two aspects of OOP prove useful here:

Inheritance

Pizza-making robots are kinds of robots, so they possess the usual robot-y properties. In OOP terms, we say they “inherit” properties from the general category of all robots. These common properties need to be implemented only once for the general case and can be reused in part or in full by all types of robots we may build in the future.

Composition

Pizza-making robots are really collections of components that work together as a team. For instance, for our robot to be successful, it might need arms to roll dough, motors to maneuver to the oven, and so on. In OOP parlance, our robot is an example of composition; it contains other objects that it activates to do its bidding. Each component might be coded as a class, which defines its own behavior and relationships.

General OOP ideas like inheritance and composition apply to any application that can be decomposed into a set of objects. For example, in typical GUI systems, interfaces are written as collections of widgets—buttons, labels, and so on—which are all drawn when their container is drawn (composition). Moreover, we may be able to write our own custom widgets—buttons with unique fonts, labels with new color schemes, and the like—which are specialized versions of more general interface devices (inheritance).

From a more concrete programming perspective, classes are Python program units, just like functions and modules: they are another compartment for packaging logic and data. In fact, classes also define new namespaces, much like modules. But, compared to other program units we’ve already seen, classes have three critical distinctions that make them more useful when it comes to building new objects:

Multiple instances

Classes are essentially factories for generating one or more objects. Every time we call a class, we generate a new object with a distinct namespace. Each object generated from a class has access to the class’s attributes and gets a namespace of its own for data that varies per object. This is similar to the per-call state retention of Chapter 17’s closure functions, but is explicit and natural in classes, and is just one of the things that classes do. Classes offer a complete programming solution.

Customization via inheritance

Classes also support the OOP notion of inheritance; we can extend a class by redefining its attributes outside the class itself in new software components coded as subclasses. More generally, classes can build up namespace hierarchies, which define names to be used by objects created from classes in the hierarchy. This supports multiple customizable behaviors more directly than other tools.

Operator overloading

By providing special protocol methods, classes can define objects that respond to the sorts of operations we saw at work on built-in types. For instance, objects made with classes can be sliced, concatenated, indexed, and so on. Python provides hooks that classes can use to intercept and implement any built-in type operation.

At its base, the mechanism of OOP in Python is largely just two bits of magic: a special first argument in functions (to receive the subject of a call) and inheritance attribute search (to support programming by customization). Other than this, the model is largely just functions that ultimately process built-in types. While not radically new, though, OOP adds an extra layer of structure that supports better programming than flat procedural models. Along with the functional tools we met earlier, it represents a major abstraction step above computer hardware that helps us build more sophisticated programs.

OOP from 30,000 Feet

Before we see what this all means in terms of code, I’d like to say a few words about the general ideas behind OOP. If you’ve never done anything object-oriented in your life before now, some of the terminology in this chapter may seem a bit perplexing on the first pass. Moreover, the motivation for these terms may be elusive until you’ve had a chance to study the ways that programmers apply them in larger systems. OOP is as much an experience as a technology.

Attribute Inheritance Search

The good news is that OOP is much simpler to understand and use in Python than in other languages, such as C++ or Java. As a dynamically typed scripting language, Python removes much of the syntactic clutter and complexity that clouds OOP in other tools. In fact, much of the OOP story in Python boils down to this expression:

object.attribute

We’ve been using this expression throughout the book to access module attributes, call methods of objects, and so on. When we say this to an object that is derived from a class statement, however, the expression kicks off a search in Python—it searches a tree of linked objects, looking for the first appearance of attribute that it can find. When classes are involved, the preceding Python expression effectively translates to the following in natural language:

Find the first occurrence of attribute by looking in object, then in all classes above it, from bottom to top and left to right.

In other words, attribute fetches are simply tree searches. The term inheritance is applied because objects lower in a tree inherit attributes attached to objects higher in that tree. As the search proceeds from the bottom up, in a sense, the objects linked into a tree are the union of all the attributes defined in all their tree parents, all the way up the tree.

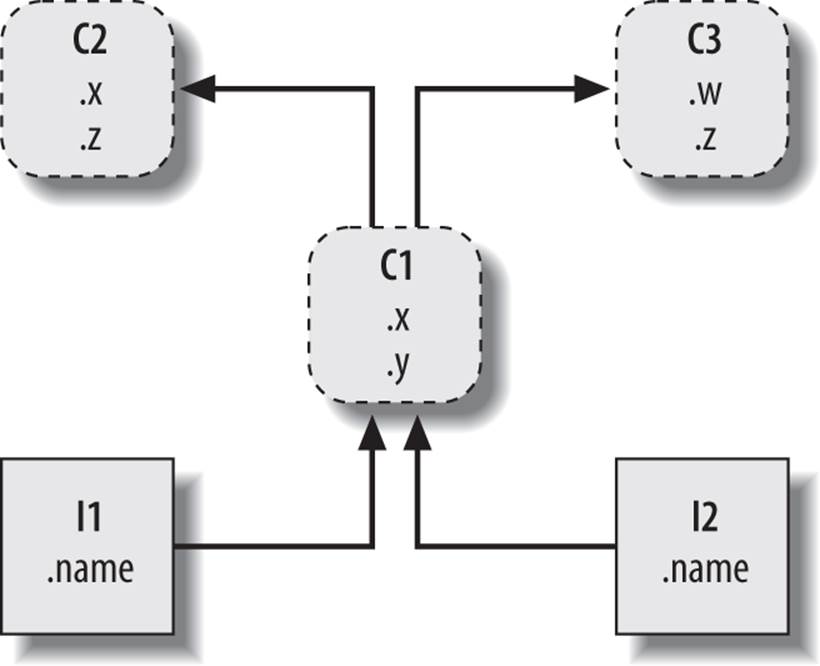

In Python, this is all very literal: we really do build up trees of linked objects with code, and Python really does climb this tree at runtime searching for attributes every time we use the object.attribute expression. To make this more concrete, Figure 26-1 sketches an example of one of these trees.

Figure 26-1. A class tree, with two instances at the bottom (I1 and I2), a class above them (C1), and two superclasses at the top (C2 and C3). All of these objects are namespaces (packages of variables), and the inheritance search is simply a search of the tree from bottom to top looking for the lowest occurrence of an attribute name. Code implies the shape of such trees.

In this figure, there is a tree of five objects labeled with variables, all of which have attached attributes, ready to be searched. More specifically, this tree links together three class objects (the ovals C1, C2, and C3) and two instance objects (the rectangles I1 and I2) into an inheritance search tree. Notice that in the Python object model, classes and the instances you generate from them are two distinct object types:

Classes

Serve as instance factories. Their attributes provide behavior—data and functions—that is inherited by all the instances generated from them (e.g., a function to compute an employee’s salary from pay and hours).

Instances

Represent the concrete items in a program’s domain. Their attributes record data that varies per specific object (e.g., an employee’s Social Security number).

In terms of search trees, an instance inherits attributes from its class, and a class inherits attributes from all classes above it in the tree.

In Figure 26-1, we can further categorize the ovals by their relative positions in the tree. We usually call classes higher in the tree (like C2 and C3) superclasses; classes lower in the tree (like C1) are known as subclasses. These terms refer to both relative tree positions and roles. Superclasses provide behavior shared by all their subclasses, but because the search proceeds from the bottom up, subclasses may override behavior defined in their superclasses by redefining superclass names lower in the tree.[50]

As these last few words are really the crux of the matter of software customization in OOP, let’s expand on this concept. Suppose we build up the tree in Figure 26-1, and then say this:

I2.w

Right away, this code invokes inheritance. Because this is an object.attribute expression, it triggers a search of the tree in Figure 26-1—Python will search for the attribute w by looking in I2 and above. Specifically, it will search the linked objects in this order:

I2, C1, C2, C3

and stop at the first attached w it finds (or raise an error if w isn’t found at all). In this case, w won’t be found until C3 is searched because it appears only in that object. In other words, I2.w resolves to C3.w by virtue of the automatic search. In OOP terminology, I2 “inherits” the attribute wfrom C3.

Ultimately, the two instances inherit four attributes from their classes: w, x, y, and z. Other attribute references will wind up following different paths in the tree. For example:

§ I1.x and I2.x both find x in C1 and stop because C1 is lower than C2.

§ I1.y and I2.y both find y in C1 because that’s the only place y appears.

§ I1.z and I2.z both find z in C2 because C2 is further to the left than C3.

§ I2.name finds name in I2 without climbing the tree at all.

Trace these searches through the tree in Figure 26-1 to get a feel for how inheritance searches work in Python.

The first item in the preceding list is perhaps the most important to notice—because C1 redefines the attribute x lower in the tree, it effectively replaces the version above it in C2. As you’ll see in a moment, such redefinitions are at the heart of software customization in OOP—by redefining and replacing the attribute, C1 effectively customizes what it inherits from its superclasses.

Classes and Instances

Although they are technically two separate object types in the Python model, the classes and instances we put in these trees are almost identical—each type’s main purpose is to serve as another kind of namespace—a package of variables, and a place where we can attach attributes. If classes and instances therefore sound like modules, they should; however, the objects in class trees also have automatically searched links to other namespace objects, and classes correspond to statements, not entire files.

The primary difference between classes and instances is that classes are a kind of factory for generating instances. For example, in a realistic application, we might have an Employee class that defines what it means to be an employee; from that class, we generate actual Employee instances. This is another difference between classes and modules—we only ever have one instance of a given module in memory (that’s why we have to reload a module to get its new code), but with classes, we can make as many instances as we need.

Operationally, classes will usually have functions attached to them (e.g., computeSalary), and the instances will have more basic data items used by the class’s functions (e.g., hoursWorked). In fact, the object-oriented model is not that different from the classic data-processing model ofprograms plus records—in OOP, instances are like records with “data,” and classes are the “programs” for processing those records. In OOP, though, we also have the notion of an inheritance hierarchy, which supports software customization better than earlier models.

Method Calls

In the prior section, we saw how the attribute reference I2.w in our example class tree was translated to C3.w by the inheritance search procedure in Python. Perhaps just as important to understand as the inheritance of attributes, though, is what happens when we try to call methods—functions attached to classes as attributes.

If this I2.w reference is a function call, what it really means is “call the C3.w function to process I2.” That is, Python will automatically map the call I2.w() into the call C3.w(I2), passing in the instance as the first argument to the inherited function.

In fact, whenever we call a function attached to a class in this fashion, an instance of the class is always implied. This implied subject or context is part of the reason we refer to this as an object-oriented model—there is always a subject object when an operation is run. In a more realistic example, we might invoke a method called giveRaise attached as an attribute to an Employee class; such a call has no meaning unless qualified with the employee to whom the raise should be given.

As we’ll see later, Python passes in the implied instance to a special first argument in the method, called self by convention. Methods go through this argument to process the subject of the call. As we’ll also learn, methods can be called through either an instance—bob.giveRaise()—or a class—Employee.giveRaise(bob)—and both forms serve purposes in our scripts. These calls also illustrate both of the key ideas in OOP: to run a bob.giveRaise() method call, Python:

1. Looks up giveRaise from bob, by inheritance search

2. Passes bob to the located giveRaise function, in the special self argument

When you call Employee.giveRaise(bob), you’re just performing both steps yourself. This description is technically the default case (Python has additional method types we’ll meet later), but it applies to the vast majority of the OOP code written in the language. To see how methods receive their subjects, though, we need to move on to some code.

Coding Class Trees

Although we are speaking in the abstract here, there is tangible code behind all these ideas, of course. We construct trees and their objects with class statements and class calls, which we’ll meet in more detail later. In short:

§ Each class statement generates a new class object.

§ Each time a class is called, it generates a new instance object.

§ Instances are automatically linked to the classes from which they are created.

§ Classes are automatically linked to their superclasses according to the way we list them in parentheses in a class header line; the left-to-right order there gives the order in the tree.

To build the tree in Figure 26-1, for example, we would run Python code of the following form. Like function definition, classes are normally coded in module files and are run during an import (I’ve omitted the guts of the class statements here for brevity):

class C2: ... # Make class objects (ovals)

class C3: ...

class C1(C2, C3): ... # Linked to superclasses (in this order)

I1 = C1() # Make instance objects (rectangles)

I2 = C1() # Linked to their classes

Here, we build the three class objects by running three class statements, and make the two instance objects by calling the class C1 twice, as though it were a function. The instances remember the class they were made from, and the class C1 remembers its listed superclasses.

Technically, this example is using something called multiple inheritance, which simply means that a class has more than one superclass above it in the class tree—a useful technique when you wish to combine multiple tools. In Python, if there is more than one superclass listed in parentheses in a class statement (like C1’s here), their left-to-right order gives the order in which those superclasses will be searched for attributes by inheritance. The leftmost version of a name is used by default, though you can always choose a name by asking for it from the class it lives in (e.g.,C3.z).

Because of the way inheritance searches proceed, the object to which you attach an attribute turns out to be crucial—it determines the name’s scope. Attributes attached to instances pertain only to those single instances, but attributes attached to classes are shared by all their subclasses and instances. Later, we’ll study the code that hangs attributes on these objects in depth. As we’ll find:

§ Attributes are usually attached to classes by assignments made at the top level in class statement blocks, and not nested inside function def statements there.

§ Attributes are usually attached to instances by assignments to the special argument passed to functions coded inside classes, called self.

For example, classes provide behavior for their instances with method functions we create by coding def statements inside class statements. Because such nested defs assign names within the class, they wind up attaching attributes to the class object that will be inherited by all instances and subclasses:

class C2: ... # Make superclass objects

class C3: ...

class C1(C2, C3): # Make and link class C1

def setname(self, who): # Assign name: C1.setname

self.name = who # Self is either I1 or I2

I1 = C1() # Make two instances

I2 = C1()

I1.setname('bob') # Sets I1.name to 'bob'

I2.setname('sue') # Sets I2.name to 'sue'

print(I1.name) # Prints 'bob'

There’s nothing syntactically unique about def in this context. Operationally, though, when a def appears inside a class like this, it is usually known as a method, and it automatically receives a special first argument—called self by convention—that provides a handle back to the instance to be processed. Any values you pass to the method yourself go to arguments after self (here, to who).[51]

Because classes are factories for multiple instances, their methods usually go through this automatically passed-in self argument whenever they need to fetch or set attributes of the particular instance being processed by a method call. In the preceding code, self is used to store a name in one of two instances.

Like simple variables, attributes of classes and instances are not declared ahead of time, but spring into existence the first time they are assigned values. When a method assigns to a self attribute, it creates or changes an attribute in an instance at the bottom of the class tree (i.e., one of the rectangles in Figure 26-1) because self automatically refers to the instance being processed—the subject of the call.

In fact, because all the objects in class trees are just namespace objects, we can fetch or set any of their attributes by going through the appropriate names. Saying C1.setname is as valid as saying I1.setname, as long as the names C1 and I1 are in your code’s scopes.

Operator Overloading

As currently coded, our C1 class doesn’t attach a name attribute to an instance until the setname method is called. Indeed, referencing I1.name before calling I1.setname would produce an undefined name error. If a class wants to guarantee that an attribute like name is always set in its instances, it more typically will fill out the attribute at construction time, like this:

class C2: ... # Make superclass objects

class C3: ...

class C1(C2, C3):

def __init__(self, who): # Set name when constructed

self.name = who # Self is either I1 or I2

I1 = C1('bob') # Sets I1.name to 'bob'

I2 = C1('sue') # Sets I2.name to 'sue'

print(I1.name) # Prints 'bob'

If it’s coded or inherited, Python automatically calls a method named __init__ each time an instance is generated from a class. The new instance is passed in to the self argument of __init__ as usual, and any values listed in parentheses in the class call go to arguments two and beyond. The effect here is to initialize instances when they are made, without requiring extra method calls.

The __init__ method is known as the constructor because of when it is run. It’s the most commonly used representative of a larger class of methods called operator overloading methods, which we’ll discuss in more detail in the chapters that follow. Such methods are inherited in class trees as usual and have double underscores at the start and end of their names to make them distinct. Python runs them automatically when instances that support them appear in the corresponding operations, and they are mostly an alternative to using simple method calls. They’re also optional: if omitted, the operations are not supported. If no __init__ is present, class calls return an empty instance, without initializing it.

For example, to implement set intersection, a class might either provide a method named intersect, or overload the & expression operator to dispatch to the required logic by coding a method named __and__. Because the operator scheme makes instances look and feel more like built-in types, it allows some classes to provide a consistent and natural interface, and be compatible with code that expects a built-in type. Still, apart from the __init__ constructor—which appears in most realistic classes—many programs may be better off with simpler named methods unless their objects are similar to built-ins. A giveRaise may make sense for an Employee, but a & might not.

OOP Is About Code Reuse

And that, along with a few syntax details, is most of the OOP story in Python. Of course, there’s a bit more to it than just inheritance. For example, operator overloading is much more general than I’ve described so far—classes may also provide their own implementations of operations such as indexing, fetching attributes, printing, and more. By and large, though, OOP is about looking up attributes in trees with a special first argument in functions.

So why would we be interested in building and searching trees of objects? Although it takes some experience to see how, when used well, classes support code reuse in ways that other Python program components cannot. In fact, this is their highest purpose. With classes, we code by customizing existing software, instead of either changing existing code in place or starting from scratch for each new project. This turns out to be a powerful paradigm in realistic programming.

At a fundamental level, classes are really just packages of functions and other names, much like modules. However, the automatic attribute inheritance search that we get with classes supports customization of software above and beyond what we can do with modules and functions. Moreover, classes provide a natural structure for code that packages and localizes logic and names, and so aids in debugging.

For instance, because methods are simply functions with a special first argument, we can mimic some of their behavior by manually passing objects to be processed to simple functions. The participation of methods in class inheritance, though, allows us to naturally customize existing software by coding subclasses with new method definitions, rather than changing existing code in place. There is really no such concept with modules and functions.

Polymorphism and classes

As an example, suppose you’re assigned the task of implementing an employee database application. As a Python OOP programmer, you might begin by coding a general superclass that defines default behaviors common to all the kinds of employees in your organization:

class Employee: # General superclass

def computeSalary(self): ... # Common or default behaviors

def giveRaise(self): ...

def promote(self): ...

def retire(self): ...

Once you’ve coded this general behavior, you can specialize it for each specific kind of employee to reflect how the various types differ from the norm. That is, you can code subclasses that customize just the bits of behavior that differ per employee type; the rest of the employee types’ behavior will be inherited from the more general class. For example, if engineers have a unique salary computation rule (perhaps it’s not hours times rate), you can replace just that one method in a subclass:

class Engineer(Employee): # Specialized subclass

def computeSalary(self): ... # Something custom here

Because the computeSalary version here appears lower in the class tree, it will replace (override) the general version in Employee. You then create instances of the kinds of employee classes that the real employees belong to, to get the correct 'margin-top:0cm;margin-right:0cm;margin-bottom:0cm; margin-left:20.0pt;margin-bottom:.0001pt;line-height:normal;vertical-align: baseline'>bob = Employee() # Default behavior

sue = Employee() # Default behavior

tom = Engineer() # Custom salary calculator

Notice that you can make instances of any class in a tree, not just the ones at the bottom—the class you make an instance from determines the level at which the attribute search will begin, and thus which versions of the methods it will employ.

Ultimately, these three instance objects might wind up embedded in a larger container object—for instance, a list, or an instance of another class—that represents a department or company using the composition idea mentioned at the start of this chapter. When you later ask for these employees’ salaries, they will be computed according to the classes from which the objects were made, due to the principles of the inheritance search:

company = [bob, sue, tom] # A composite object

for emp in company:

print(emp.computeSalary()) # Run this object's version: default or custom

This is yet another instance of the idea of polymorphism introduced in Chapter 4 and expanded in Chapter 16. Recall that polymorphism means that the meaning of an operation depends on the object being operated on. That is, code shouldn’t care about what an object is, only about what itdoes. Here, the method computeSalary is located by inheritance search in each object before it is called. The net effect is that we automatically run the correct version for the object being processed. Trace the code to see why.[52]

In other applications, polymorphism might also be used to hide (i.e., encapsulate) interface differences. For example, a program that processes data streams might be coded to expect objects with input and output methods, without caring what those methods actually do:

def processor(reader, converter, writer):

while True:

data = reader.read()

if not data: break

data = converter(data)

writer.write(data)

By passing in instances of subclasses that specialize the required read and write method interfaces for various data sources, we can reuse the processor function for any data source we need to use, both now and in the future:

class Reader:

def read(self): ... # Default behavior and tools

def other(self): ...

class FileReader(Reader):

def read(self): ... # Read from a local file

class SocketReader(Reader):

def read(self): ... # Read from a network socket

...

processor(FileReader(...), Converter, FileWriter(...))

processor(SocketReader(...), Converter, TapeWriter(...))

processor(FtpReader(...), Converter, XmlWriter(...))

Moreover, because the internal implementations of those read and write methods have been factored into single locations, they can be changed without impacting code such as this that uses them. The processor function might even be a class itself to allow the conversion logic ofconverter to be filled in by inheritance, and to allow readers and writers to be embedded by composition (we’ll see how this works later in this part of the book).

Programming by customization

Once you get used to programming this way (by software customization), you’ll find that when it’s time to write a new program, much of your work may already be done—your task largely becomes one of mixing together existing superclasses that already implement the behavior required by your program. For example, someone else might have written the Employee, Reader, and Writer classes in this section’s examples for use in completely different programs. If so, you get all of that person’s code “for free.”

In fact, in many application domains, you can fetch or purchase collections of superclasses, known as frameworks, that implement common programming tasks as classes, ready to be mixed into your applications. These frameworks might provide database interfaces, testing protocols, GUI toolkits, and so on. With frameworks, you often simply code a subclass that fills in an expected method or two; the framework classes higher in the tree do most of the work for you. Programming in such an OOP world is just a matter of combining and specializing already debugged code by writing subclasses of your own.

Of course, it takes a while to learn how to leverage classes to achieve such OOP utopia. In practice, object-oriented work also entails substantial design work to fully realize the code reuse benefits of classes—to this end, programmers have begun cataloging common OOP structures, known as design patterns, to help with design issues. The actual code you write to do OOP in Python, though, is so simple that it will not in itself pose an additional obstacle to your OOP quest. To see why, you’ll have to move on to Chapter 27.

[50] In other literature and circles, you may also occasionally see the terms base classes and derived classes used to describe superclasses and subclasses, respectively. Python people and this book tend to use the latter terms.

[51] If you’ve ever used C++ or Java, you’ll recognize that Python’s self is the same as the this pointer, but self is always explicit in both headers and bodies of Python methods to make attribute accesses more obvious: a name has fewer possible meanings.

[52] The company list in this example could be a database if stored in a file with Python object pickling, introduced in Chapter 9, to make the employees persistent. Python also comes with a module named shelve, which allows the pickled representation of class instances to be stored in an access-by-key filesystem; we’ll deploy it in Chapter 28.

Chapter Summary

We took an abstract look at classes and OOP in this chapter, taking in the big picture before we dive into syntax details. As we’ve seen, OOP is mostly about an argument named self, and a search for attributes in trees of linked objects called inheritance. Objects at the bottom of the tree inherit attributes from objects higher up in the tree—a feature that enables us to program by customizing code, rather than changing it or starting from scratch. When used well, this model of programming can cut development time radically.

The next chapter will begin to fill in the coding details behind the picture painted here. As we get deeper into Python classes, though, keep in mind that the OOP model in Python is very simple; as we’ve seen here, it’s really just about looking up attributes in object trees and a special function argument. Before we move on, here’s a quick quiz to review what we’ve covered here.

Test Your Knowledge: Quiz

1. What is the main point of OOP in Python?

2. Where does an inheritance search look for an attribute?

3. What is the difference between a class object and an instance object?

4. Why is the first argument in a class’s method function special?

5. What is the __init__ method used for?

6. How do you create a class instance?

7. How do you create a class?

8. How do you specify a class’s superclasses?

Test Your Knowledge: Answers

1. OOP is about code reuse—you factor code to minimize redundancy and program by customizing what already exists instead of changing code in place or starting from scratch.

2. An inheritance search looks for an attribute first in the instance object, then in the class the instance was created from, then in all higher superclasses, progressing from the bottom to the top of the object tree, and from left to right (by default). The search stops at the first place the attribute is found. Because the lowest version of a name found along the way wins, class hierarchies naturally support customization by extension in new subclasses.

3. Both class and instance objects are namespaces (packages of variables that appear as attributes). The main difference between them is that classes are a kind of factory for creating multiple instances. Classes also support operator overloading methods, which instances inherit, and treat any functions nested in the class as methods for processing instances.

4. The first argument in a class’s method function is special because it always receives the instance object that is the implied subject of the method call. It’s usually called self by convention. Because method functions always have this implied subject and object context by default, we say they are “object-oriented” (i.e., designed to process or change objects).

5. If the __init__ method is coded or inherited in a class, Python calls it automatically each time an instance of that class is created. It’s known as the constructor method; it is passed the new instance implicitly, as well as any arguments passed explicitly to the class name. It’s also the most commonly used operator overloading method. If no __init__ method is present, instances simply begin life as empty namespaces.

6. You create a class instance by calling the class name as though it were a function; any arguments passed into the class name show up as arguments two and beyond in the __init__ constructor method. The new instance remembers the class it was created from for inheritance purposes.

7. You create a class by running a class statement; like function definitions, these statements normally run when the enclosing module file is imported (more on this in the next chapter).

8. You specify a class’s superclasses by listing them in parentheses in the class statement, after the new class’s name. The left-to-right order in which the classes are listed in the parentheses gives the left-to-right inheritance search order in the class tree.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.