Total Information Risk Management (2014)

PART 1 Total Information Risk Management Background

CHAPTER 4 Introduction to Enterprise Risk Management

Abstract

This chapter introduces the most important elements of risk management. We explain risk and risk management, what a risk management process does, and how risk can be assessed and treated in general. Moreover, it is shown how the risk appetite and risk criteria can be determined, and the role of the chief risk officer is discussed.

Keywords

Risk; Risk Management; Risk Management Process; Risk Appetite; Risk Assessment; Risk Treatment; Chief Risk Officer

What you will learn in this chapter

![]() What is risk and risk management

What is risk and risk management

![]() What is a risk management process

What is a risk management process

![]() How to determine risk appetite and risk criteria

How to determine risk appetite and risk criteria

![]() How risk can be assessed and treated

How risk can be assessed and treated

![]() What is the role of chief risk officer

What is the role of chief risk officer

Introduction

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first books that shows, comprehensively, how well-established risk management methods can be applied to the relatively new discipline of information management to assess and understand the business impact of information and its quality. Additionally, we will demonstrate how the benefits of information risk treatment options can be systematically and rigorously evaluated based on a thorough information risk analysis. We will commence this journey by providing you with a brief introduction to the essentials of risk management.

What is risk?

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in the ISO Guide 73 defines risk as the “effect of uncertainty on objectives” (ISO, 2009a).

Let’s digest this definition a little more by considering its individual elements and how they are defined in the Oxford Dictionary (http://oxforddictionaries.com/). First of all, risk is an effect, which the Oxford Dictionary defines as “a change, which is a result or consequence of an action or other cause.” So, a risk has to have a cause and it results in a change. If, for example, an individual smoke cigarettes, it increases the risk of lung cancer, which would certainly change his or her life if he or she were unfortunate enough to contract lung cancer.

The reason for a risk is uncertainty. Uncertainty is “the state of being uncertain.” Uncertain means “not able to be relied on; not known or definite.” Imagine that you would like to purchase a property in San Francisco, which is known for its susceptibility to earthquakes. You know that there is a risk of an earthquake occurring at any time, but you simply cannot say if there will be an earthquake during the next three years or not. It is uncertain.

And finally, this effect causes a change that has an impact on an objective. An objective is “a thing aimed at or sought; a goal.” In private life, that same individual may have an objective “to live a happy and healthy life.” Both an earthquake and contracting lung cancer would negatively impact the objective.

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

Risk is the effect of uncertainty on objectives (ISO, 2009a).

Risk can be negative or positive. Earthquakes and diseases are classic examples of negative risk. In contrast, when somebody plays roulette in a casino, he or she hopes for a positive risk. In a way, this is counterintuitive to the manner in which we use the wordrisk in our everyday language. We often talk about risk as something inherently bad, for example, health risks (e.g., smoking increases the risk of cancer), natural disasters like earthquakes and floods, and sudden economic downturns. But, in fact, the basis of our market economy is actually taking risks. A merger or takeover of a company is often pursued because the acquiring party expects that it is worth the price of acquisition because it anticipates that future financial returns will be favorable—this is positive risk taking.

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

An effect is a deviation from the expected—positive and/or negative (ISO, 2009a).

Risk can be measured, depending on its nature, using either a statistical approach that uses historical data or a subjective probability approach in an informed decision. Both approaches are frequently used in practice. When assessing risk, one has to keep in mind that risk is context-dependent since it reshapes when the system changes.

What is Enterprise Risk Management?

Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) is a relatively new discipline that requires “that an organization looks at all the risks that it faces across all of the operations that it undertakes” (Hopkin, 2010).

The ISO Guide 73 defines risk management as “coordinated activities to direct and control an organization with regard to risk” (ISO, 2009a). Risk management in an organization often has multiple objectives (e.g., high safety and low costs), which requires adequate modeling and optimization techniques that can take multiple objectives into account.

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

Risk management is a series of coordinated activities to direct and control an organization with regard to risk (ISO, 2009a).

Haimes introduced the concept of total risk management, which he defines as “a systematic, statistically based, holistic view that builds on a formal risk assessment and management” (Haimes, 2009). Total risk management addresses four sources of failure:

1. Hardware failure

2. Software failure

3. Organizational failure

4. Human failure

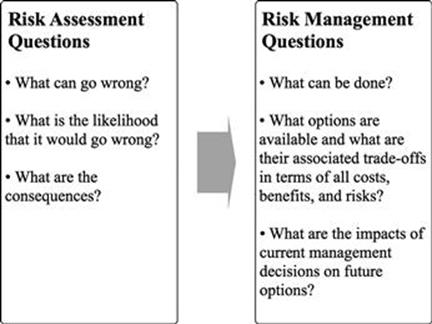

Risk assessment and management questions that need to be addressed are shown in Figure 4.1.

![]() THEORETICAL EXCURSION: AN OVERVIEW OF RISK MANAGEMENT STANDARDS

THEORETICAL EXCURSION: AN OVERVIEW OF RISK MANAGEMENT STANDARDS

There have been several risk management standards proposed in the literature, which are shown in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1

Risk Management Standards

|

Standard |

Description |

|

CoCo(Criteria of Control) |

Framework produced by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (1995) |

|

Institute of Risk Management (IRM) |

Standard produced jointly by AIRMIC, ALARM, and the IRM (2002) |

|

Orange Book |

Standard produced by HM Treasury of the U.K. government (2004) |

|

COSO ERM |

Framework produced by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Committee (2004) |

|

Turnbull Report |

Framework produced by the Financial Reporting Council (2005) |

|

ISO 31000 |

Standard published by the International Standards Organization (2009) |

|

British Standard BS 31100 |

Standard published by the British Standards Institution (2011) |

Source: Hopkin, 2010.

A risk management standard consists of a risk management process together with a complementary risk management framework. Regarding the question as to which standard an organization should adopt, Hopkin gives the following advice: “Although some standards are better recognized than others, organizations should select the approach that is most relevant to their particular circumstances” (Hopkin, 2010). The key components of risk management standards are the risk management framework and process. Each standard is described in the following.

The CoCo (Criteria of Control) framework is a risk management standard that has been developed by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants, 1995). This framework follows a culture of risk awareness approach, in contrast to the risk management approach by ISO 31000, BS 31100, and IRM, and in contrast to the internal control approach developed by the COSO framework and Turnbull Report (1999).

The standard published by the IRM is a joint effort of the major risk management organizations in the United Kingdom: IRM, The Association of Insurance and Risk Managers (AIRMIC), The National Forum for Risk Management in the Public Sector (ALARM) (IRM, 2002). This framework provides a risk management terminology, process, and organizational structure and objective. As in the ISO 31000 standard, risk can be both upside and downside.

The Orange Book is a risk management standard for government organizations and has been developed by the HM Treasury of the U.K. government (HM Treasury, 2004). The standard comprises definitions, a comprehensive risk management model, and a clearly explained risk management process. It is emphasized that risk management has to often go beyond the boundaries of an organization, since there are in any organization, a number of interdependencies with other organizational entities.

COSO ERM is an internal control framework for companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange; it is recognized by the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX), and as a result is the most used risk framework in the United States (Moeller, 2011). Key components of enterprise risk management are identified: internal environment, objective setting, event identification, risk assessment, risk response, control activities, information, communication, and monitoring. The components do not form a serial process, but rather a multidirectional process.

The Turnbull Report, the official name of which is “Internal Control: Guidance for Directors on the Combined Code,” was created in 1999 with the London Stock Exchange for listed companies (Turnbull, 1999). It is an accepted alternative to the COSO ERM framework regarding Sarbanes–Oxley compliance.

ISO 31000 is a family of standards published by the International Standards Organization, which currently consists of the ISO Guide 73 “Risk Management—Vocabulary” (ISO, 2009a) that contains definitions for risk management terms; ISO 31000 “Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines” (ISO, 2009b) that contains guidelines for risk management and includes a risk management framework and process; and ISO 31010 “Risk Management—Risk Assessment Techniques” (ISO, 2009c) that summarizes established techniques for risk assessment.

Similar to ISO 31000, the standard BS 31100 published by the British Standards Institution proposes a risk management framework and process (British Standards Institution, 2011).

FIGURE 4.1 Risk assessment and management questions. (Source: Haimes, 2009.)

What is the generic risk management process?

A risk management process is the “systematic application of management policies, procedures, and practices to the activities of communicating, consulting, establishing the context, and identifying, analyzing, evaluating, treating, monitoring, … and reviewing risk” (ISO, 2009a).

Many different risk management processes have been proposed in the literature, which typically contain steps like: (1) identification of risks, (2) assessment/measurement of risks, (3) evaluation, choice, and implementation of risk mitigation options, and (4) monitoring of risk mitigation. Risk management processes are often divided into the two main stages of assessing risk and treating risk.

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

A risk management process is a systematic process to assess and treat risks.

Assessment of risk

Risk management is concerned with ensuring that an organization recognizes and understands where weaknesses exist and/or where they might arise, and is proactive in addressing those to ensure that there is no adverse interruption to business continuity and/or damage to its reputation. An integral part is therefore the assessment of risk (ISO, 2009a):

![]() Risk assessment is the “overall process of risk identification, … risk analysis, … and risk evaluation.”

Risk assessment is the “overall process of risk identification, … risk analysis, … and risk evaluation.”

![]() Risk identification is the “process of finding, recognizing, and describing risks.”

Risk identification is the “process of finding, recognizing, and describing risks.”

![]() Risk analysis is the “process to comprehend the nature of risk … and to determine the level of risk.”

Risk analysis is the “process to comprehend the nature of risk … and to determine the level of risk.”

![]() Risk evaluation is the “process of comparing the results of risk analysis … with risk criteria … to determine whether the risk … and/or its magnitude is acceptable or tolerable.”

Risk evaluation is the “process of comparing the results of risk analysis … with risk criteria … to determine whether the risk … and/or its magnitude is acceptable or tolerable.”

The starting place for organizations is to first identify the risks it faces, then monitor for risk, and develop policies and strategies for minimizing risk and planning for contingencies. Risk is managed through information and knowledge; knowing the inherent risks enables appropriate minimization policies and strategies, as well as early warning systems, to be designed.

There are different ways in which risk identification might take place. Typically, it will involve an internal assessment, ideally organization wide although some might wish to start in a specific (key) department where the risks are perceived to be the greatest. Some organizations might involve their auditors in such an exercise and others may call in external consultants to assist.

An organization that already has a good information and knowledge management strategy, where sharing information and knowledge is commonplace, will probably be more ready to identify risks than one where the concept of “information is power” prevails.

Involving employees at this early stage in the identification of risks will undoubtedly reap rewards. It is the people involved in the day-to-day operations who understand all the nuances of their operations who are normally best able to judge what is or is not a risk. That said, an external perspective is also good business practice as sometimes there is a danger that when an employee is working very closely with matters, he or she may not always have a clear appreciation of the risks involved in the day-to-day activities.

![]() ACTION TIP

ACTION TIP

One of the key concepts in knowledge management is the custom of setting up communities of interest/practice to share knowledge, and these can be a very useful initiative to employ when thinking about ways in which to identify risk. Bringing together people who share a common interest to discuss and debate issues can produce invaluable insights and consider options upon which to move forward.

Once risks have been identified, they should be analyzed in terms of their likelihood of occurrence and their impact. To some extent, the impact might be a quite subjective exercise. Perhaps one of the easiest ways in terms of thinking about impact is to think about it in association with the organization’s primary objectives; for example, in a commercial organization, what would the financial impact be? Another organization might focus on the cost of losing brand share or buyer/supplier relationships. Whatever method of evaluation is used, it should be consistent and clearly understood by all involved.

Consequently, risk has two important aspects:

1. Occurrence: think about the frequency—when will it occur? Daily, weekly, monthly, or annually?

2. Impact: will it be high, medium, or low?

Once these aspects have been calculated, we suggest that it might be a useful exercise to plot them on a matrix. After having plotted, the risks can be classified according to their impact into high, medium, or low categories. Table 4.2 (using a simple matrix) shows how risks are allocated: the high risk is the top right, low risk is the bottom left, and the two medium-level risks are top left and bottom right.

Table 4.2

Risk Allocation Matrix

|

High impact/low occurrence |

High impact/high occurrence |

|

Low impact/low occurrence |

High occurrence/low impact |

The risks have to be evaluated by comparing them to defined risk criteria. These criteria will differ from one organization to another and are closely linked to the risk appetite of the organization.

With the constantly changing environment, organizations should also be scanning the horizon on a regular basis to identify new risks.

There are many techniques available for risk assessment; a good overview is given in the ISO 31010 document (ISO, 2009c). They range from simple techniques like brainstorming and structured or semi-structured interviews to more sophisticated tools like fault tree analysis, Bayesian statistics, and Monte Carlo simulations. A thorough introduction to the more complex statistically based risk assessment tools is given by Haimes (2009). Chapter 11 of this book discusses how some of these risk assessment techniques can be used for managing information risks.

Risk appetite and risk criteria

An important facet in managing risk effectively is to determine what your organization’s risk appetite is. Risk appetite is the amount of risk exposure, or potential adverse impact from an event/situation, that the organization is willing to accept/retain. Once an organization has established their risk appetite threshold, also called the risk criteria, if it is breached, risk management initiatives are prompted to bring the risk exposure back to an acceptable level.

In some instances, the risk levels will be high and in others a much more cautious stance will be taken. There will always be some risks that are unavoidable; in such cases you need to ensure that you have good contingency plans in place.

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

Only you can determine what level of risk you are willing to tolerate in a particular scenario. You should set the risk criteria based on your risk appetite.

There are no standard benchmarks for identifying what level of risk an organization should take; however, we hope that providing you with some guidelines in terms of questions that should be asked will help you to formulate your own risk appetite to the specific situations that might occur in your organization.

To help your organization determine its risk appetite and risk criteria, consider first the mapping that has already been done to determine occurrence and impact of risk and the assessment you have completed establishing whether it is a high, medium, or low risk, then consider the following questions:

![]() In which areas of risk should you prioritize your risk appetite? (Typically, this would be the areas you have already identified as high risk.)

In which areas of risk should you prioritize your risk appetite? (Typically, this would be the areas you have already identified as high risk.)

![]() Where should you allocate your finite time and resources to minimize risk exposures? (Suggest that the high-risk areas are the ones to focus resources on.)

Where should you allocate your finite time and resources to minimize risk exposures? (Suggest that the high-risk areas are the ones to focus resources on.)

![]() Which risks do you consider need early attention to reduce the level of current exposure?

Which risks do you consider need early attention to reduce the level of current exposure?

![]() What level of risk requires a formal response strategy to mitigate the potentially adverse impact?

What level of risk requires a formal response strategy to mitigate the potentially adverse impact?

![]() What level of risk requires escalation to a higher authority?

What level of risk requires escalation to a higher authority?

![]() How have you managed past events?

How have you managed past events?

![]() What did you learn from earlier experiences?

What did you learn from earlier experiences?

Treatment of risk

Having identified and assessed the risks, the next stage is to decide how to treat those risks. Risk treatment (equivalent to risk response) is defined by ISO Guide 73 as the “process to modify risk” (ISO, 2009a). There are different ways described in the ISO Guide 73 as to how risk can be treated:

![]() Avoiding the risk by deciding not to start or continue with the activity that gives rise to the risk.

Avoiding the risk by deciding not to start or continue with the activity that gives rise to the risk.

![]() Taking or increasing risk to pursue an opportunity.

Taking or increasing risk to pursue an opportunity.

![]() Removing the risk source.

Removing the risk source.

![]() Changing the likelihood.

Changing the likelihood.

![]() Changing the consequences.

Changing the consequences.

![]() Sharing the risk with another party or parties.

Sharing the risk with another party or parties.

![]() Retaining the risk by informed decision.

Retaining the risk by informed decision.

Another popular easily recallable framework is the four T’s of hazard risk management: tolerate, treat, transfer, and terminate (Hopkin, 2010).

![]() Tolerate (detective) is basically the decision to do nothing, because no further action needs or can be taken—the risk is accepted and is further monitored.

Tolerate (detective) is basically the decision to do nothing, because no further action needs or can be taken—the risk is accepted and is further monitored.

![]() Treat (corrective) is acting upon the risk to control or reduce the risk (partially) and the frequent ways risks are addressed in an organization.

Treat (corrective) is acting upon the risk to control or reduce the risk (partially) and the frequent ways risks are addressed in an organization.

![]() Transfer (directive) means that the risk is shared or transferred completely to a third party (e.g., an insurance company) or by signing other types of contracts that transfer the risk.

Transfer (directive) means that the risk is shared or transferred completely to a third party (e.g., an insurance company) or by signing other types of contracts that transfer the risk.

![]() Terminate (preventive) is the option to stop the activities that lead to the risk.

Terminate (preventive) is the option to stop the activities that lead to the risk.

![]() EXAMPLE

EXAMPLE

Accept the Risk (Tolerate)

![]() Risk-taking is something that organizations often have to do to remain competitive, therefore, in some cases, decisions will be taken to accept these and absorb any losses. The same will apply in those situations where risks have not been identified and consequent loss occurs. In these types of circumstances there should be a contingency plan in place to address any adverse impact in the event that the risk becomes real.

Risk-taking is something that organizations often have to do to remain competitive, therefore, in some cases, decisions will be taken to accept these and absorb any losses. The same will apply in those situations where risks have not been identified and consequent loss occurs. In these types of circumstances there should be a contingency plan in place to address any adverse impact in the event that the risk becomes real.

Transfer the Risk (Transfer)

![]() Insuring against risk usually is the same as transferring the risk. Another method would be to share the risk with a third party (e.g., customers, suppliers, or subcontractors). Some insurance companies will lower premiums if they can see that there is a thorough risk management strategy in place. Organizations are legally obliged to seek cover for certain situations (e.g., employers’ liability insurance, vehicles, etc.).

Insuring against risk usually is the same as transferring the risk. Another method would be to share the risk with a third party (e.g., customers, suppliers, or subcontractors). Some insurance companies will lower premiums if they can see that there is a thorough risk management strategy in place. Organizations are legally obliged to seek cover for certain situations (e.g., employers’ liability insurance, vehicles, etc.).

Reduce the Risk (Treat)

![]() The greatest number of risks will be treated in this way. This is where effective risk management comes into its own. Actions to reduce the risks to an acceptable level are set in motion. Examples include having backup staffing arrangements in the event of absence, maintaining equipment in good working order, installing automatic sprinkler systems, adhering to health and safety guidelines, keeping backup copies of computer software, building evacuation procedures, having contingency plans, working with pressure groups, etc.

The greatest number of risks will be treated in this way. This is where effective risk management comes into its own. Actions to reduce the risks to an acceptable level are set in motion. Examples include having backup staffing arrangements in the event of absence, maintaining equipment in good working order, installing automatic sprinkler systems, adhering to health and safety guidelines, keeping backup copies of computer software, building evacuation procedures, having contingency plans, working with pressure groups, etc.

Eliminate the Risk (Terminate)

![]() Some risks will only be managed effectively by eliminating them completely. This may not always be possible or indeed desirable; however, some risks in business operations may be so high that it is not judicious to proceed with them. Another way of eliminating some types of risks is to seek payments upfront.

Some risks will only be managed effectively by eliminating them completely. This may not always be possible or indeed desirable; however, some risks in business operations may be so high that it is not judicious to proceed with them. Another way of eliminating some types of risks is to seek payments upfront.

Chief risk officer

With systematically high-profile corporate failures occurring with what seems like an alarming regularity, it is not at all unusual to see organizations in a wide range of industries appointing a chief risk officer (CRO). Traditionally, this position has been seen in sectors such as financial services and energy companies, however, recent years have witnessed the emergence of the CRO role in a growing range of industries. The CRO is responsible for formulating the information policies and information strategies associated with organization-wide risk management including information risk. The CRO is responsible for coordinating all risk management initiatives across the entire organization, guiding the organization’s response to the increasingly regulated and legal environment, keeping the board of directors apprised of risk issues, ensuring that risks taken do not compromise business continuity, and guiding staff.

The CRO needs to be alert to what is happening in the wider environment and must monitor emergent risks that might impact on the organization and be proactive in developing appropriate responses to such. It is not the CRO’s responsibility to manage every risk in every part of the organization—accountability for management of risk lies collectively within the organization.

CROs come from a wide variety of organizational disciplines, for example, internal audit, finance, strategic planning, or legal. It is useful if the CRO has cross-functional expertise and an understanding of how the different parts of the organization fit together to form the whole. Having an overview of the risks facing the organization, having the authority to make change happen, being able to think strategically, having good analytical skills, and be able to influence activity across the organization are all key aspects of the role.

At first glance, the CRO role might seem to contradict the principle that risk management should be a collective responsibility; however, it is very helpful to have someone who steers matters, focuses on relevant activities, and coordinates initiatives that might otherwise be inefficient or even contradictory.

Summary

Risk management is a well-established discipline that offers a number of publicly available and internationally recognized standards that are widely used in many organizations. Risk management standards usually consist of two main components. Risk management processes offer a structured, comprehensive, and standardized approach to manage risks, while risk management frameworks show how the risk management process can be integrated and used within an organization. Risk management processes can be divided into two main phases: risk assessment, in which risks are identified, analyzed, and evaluated, and risk treatment, which is about responding to the identified risks. There are many different tools that can be used for risk assessment; these range from simple tools to very sophisticated mathematical models. For example, risk management has been applied in the information systems discipline in two ways: (1) management of risks that result from IT malfunction, and (2) management of risks that arise from information security problems. A need to use risk management techniques for managing risks that arise from poor information quality has been identified, however, to our knowledge, there is currently no research available that shows how to apply risk management principles and tools to the information quality discipline.

Risk management, as a discipline in its own right, is moving higher up the business agenda. Tolerance for error in managing risk, from all organizational stakeholders as well as the general public, is lower than hitherto and senior management is now being held personally accountable for failure to manage risk effectively. Failing to manage risk effectively can quite easily become a critical issue, sometimes even fatal, so having policies and frameworks within which to manage risk is vital to continuity and success. The regulatory environment is becoming stricter with government and authorities placing ever-more stringent requirements on organizations to comply with legal and regulatory frameworks.

Organizations that have adopted risk management methodologies are better placed to ensure that operations are successful and the potential damage from risk is reduced.

Risk management should be integrated in day-to-day operations and become part of the culture, with everyone in the organization being responsible for managing risk in their sphere of work. This can be facilitated by a CRO who has overall responsibility for ensuring that risk throughout the organization is being managed effectively by developing and establishing appropriate policies, frameworks, and methodologies.

Risk management can no longer be taken lightly; it needs to be given due attention and it needs to be an achievable goal. With the right amount of effort, proper preparation, and planning, as well as resourcing, organizations should be able to formulate risk management strategies and policies, thus ensuring their readiness and ability to deal with adverse situations should they arise.

Remember too that managing risk is not a one-off exercise but rather something that should be done and, importantly, reviewed on a regular basis. Risks change and complacency is not an option. Organizations that implement risk management procedures mitigate the consequences of the worst disasters that might befall them.

References

1. British Standards Institution. BS 31100:2011—Risk Management. Code of Practice and Guidance for the Implementation of BS ISO 31000. BSi 2011.

2. Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants. Guidance on Control. 1995; Canada. Available at http://www.rogb.ca/publications/item12613.aspx; 1995.

3. Carnegie Mellon University. Continuous Risk Management Overview. 2004; Available at http://www.sei.cmu.edu/risk/overview.html; 2004.

4. Institute of Risk Management. A Risk Management Standard IRM, AIRMIC, and ALARM. 2002; Available at http://www.theirm.org/publications/documents/ARMS_2002_IRM.pdf; 2002.

5. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO Guide 73:2009—Risk Management—Vocabulary. 2009a; Available at http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=44651; 2009a.

6. ISO. ISO 31000:2009—Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines on Implementation. 2009b; Available at http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail?csnumber=43170; 2009b.

7. ISO. ISO/IEC 31010:2009—Risk Management—Risk Assessment Techniques. 2009c; Available at http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail?csnumber=43170; 2009c.

8. Haimes YY. Risk Modeling, Assessment, and Management. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2009.

9. Treasury HM. The Orange Book: Management of Risk—Principles and Concepts. 2004; Available at http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/orange_book.htm; 2004.

10. Hopkin P. Fundamentals of Risk Management: Understanding Evaluating and Implementing Effective Risk Management. 2010.

11. Moeller RR. COSO Enterprise Risk Management: Establishing Effective Governance, Risk, and Compliance (GRC) Processes. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2011.

12. Turnbull N, Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales. Internal Control: Guidance for Directors on the Combined Code. London, United Kingdom: Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales; 1999.