Total Information Risk Management (2014)

PART 2 Total Information Risk Management Process

CHAPTER 6 TIRM Process Stage A

Establish the Context

Abstract

This chapter is a step-by-step guide for implementing Stage A, establishing the context, of the TIRM process.

Keywords

Motivation; Goals and Scope of TIRM; External Environment; Organizational Context; Business Objectives; Measurement Units; Risk Criteria; Information Environment

What you will learn in this chapter

![]() How to set the motivation, goals, initial scope, responsibilities, and context of the TIRM process

How to set the motivation, goals, initial scope, responsibilities, and context of the TIRM process

![]() How to establish the external environment

How to establish the external environment

![]() How to analyze the organization

How to analyze the organization

![]() How to identify business objectives, measurement units, and risk criteria

How to identify business objectives, measurement units, and risk criteria

![]() How to get a thorough understanding of the information environment

How to get a thorough understanding of the information environment

Introduction

Motivation and goals for stage A

The goal of this stage is to establish the context for Total Information Risk Management (TIRM). Imagine you want to build a new house. You probably would initially need to make a number of preparations before the actual building of the house commences. You need to purchase a plot of land to build the property on and hire an architect to design the house. The assessment and treatment of information risks also requires some preparation. As in the analogy of the construction of a house, some of the key decisions in the TIRM process are made at the very beginning, when establishing the context. For instance, you need to decide early on what the motivation and goals are of applying the TIRM process in your organization. You need also to set a scope and define the responsibilities and context of the process. But, this is not enough. If you want to successfully facilitate the process, you have to develop a good understanding of the environment your organization is in, both internally and externally.

It should not be too surprising that you also require a good understanding of the important IT systems and information management processes in your organization. As risk is the effect of uncertainty on business objectives, you need to understand the information aspects of the core business objectives in your organization and you also need to determine how these should be measured. The benefit of this stage is that you can execute the succeeding stages more effectively. Please take this stage seriously. If the architect has done a poor job at the start, it will be very difficult to compensate for that initial poor job at a later stage. Once the building of the house has commenced and is in progress, you could lose a lot of time and waste resources if things have not been done properly from the start.

Overview of stage A

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

A lot of the information that needs to be collected as part of stage A will be already documented in your organization, so you just need to find the right documents, extract the essentials from these, and refer to the documents so that the details can be easily accessed if needed.

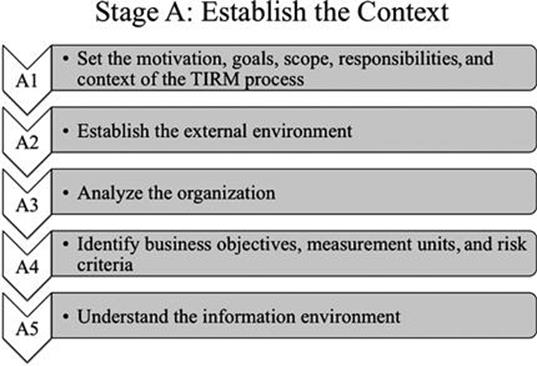

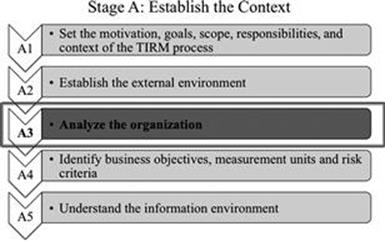

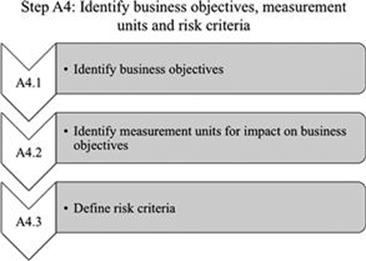

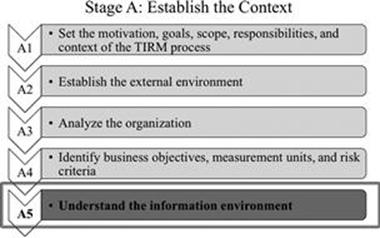

Stage A consists of five steps as shown in Figure 6.1. First, the motivation, goals, scope, responsibilities, and context of the TIRM process are set in step A1. The external environment needs to be established in step A2, followed by an analysis of the organization in step A3. Moreover, business objectives, measurement units, and risk criteria need to be identified in step A4. The final step, A5, establishes the information environment.

FIGURE 6.1 Five steps to establishing the context.

Some of the information to establish the context can be collected by interviewing managers from different functions, those who have a good overview of the organization. A lot of the information will already be documented in most organizations, so you just need to find the right documents, extract the essentials from these, and refer to the documents so you or somebody else can look up the details if needed.

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

The time and resources you spend establishing the context in stage A should be proportional to the scope of the TIRM process. Make sure that the majority of the time and resource allocation is reserved for stages B and C.

Output of this stage

![]() The motivation and goals for implementing the TIRM process.

The motivation and goals for implementing the TIRM process.

![]() A defined scope, responsibilities, and context for applying the TIRM process.

A defined scope, responsibilities, and context for applying the TIRM process.

![]() An understanding of the organization’s external, internal, and information environments.

An understanding of the organization’s external, internal, and information environments.

![]() Identified key business objectives in your organization and measurement scales to quantify the objectives.

Identified key business objectives in your organization and measurement scales to quantify the objectives.

![]() Risk criteria for each business objective.

Risk criteria for each business objective.

![]() General information management issues.

General information management issues.

TIRM project kickoff

To implement the TIRM process in your organization, you need first to convince and educate other people about the usefulness of the TIRM process and explain at a basic level how it works. In particular, you need to establish senior management support. Therefore, a sensible tactic is to invite people who have expressed an interest in being involved to a presentation about the TIRM process (e.g., the one that you can find in the online book companion website). Then, organize, a two- to three-hour workshop with the interested parties during which you convince them to participate in step A1.

WHAT IF YOU DO NOT HAVE SENIOR LEADERSHIP COMMITMENT FOR TIRM?

Often, it is hard to convince senior leadership to engage, as they are preoccupied with too many things. It is usually easier to gain the support of the leadership of a smaller business unit rather than the support of top executives. Choose leaders of business units who show the most enthusiasm for data and information improvement projects. Restricting the scope of the TIRM process application to a particular, smaller business unit or segment can be a useful strategy; this is particularly appropriate if you have not been able to get the support of the executive leadership to the implementation of the TIRM process. If the implementation of the TIRM process in the small initial scope is successful, this might give you the opportunity to convince other business units to participate in the future, as you will have a success story to tell.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

We will illustrate all the steps in the following commentary, using a fictitious case study of a call center, which is under constant pressure to fully satisfy customers but suffers from decreasing profit margins. A data quality manager believes that higher customer satisfaction at a lower cost can be achieved if data and information is of higher quality and is used more effectively. He convinces the managing director of the call center to implement the TIRM process to identify optimal data and information quality improvement investments that promise the best benefit-to-cost ratio.

Step A1: Set the motivation, goals, initial scope, responsibilities, and context of the TIRM process

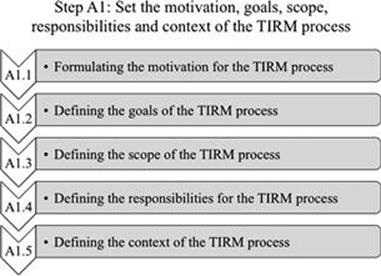

The first step (Figure 6.2) contains a number of activities to kick off the TIRM process, shown in Figure 6.3.

FIGURE 6.2 Step A1 in context.

FIGURE 6.3 Activities in step A1.

A.1.1 Formulating the motivation for the TIRM process

The TIRM process can be started by asking the question “What is our motivation for implementing the process?”

There is a reason why you want to implement the TIRM process in your organization. Other people who you have convinced to participate in and support the implementation will also have a reason why they support you. In this step, it is all about agreeing on a common motivation that serves as a mission for the entire process implementation. In practice, the senior executive who will sponsor the implementation has a major say in what the motivation for the process will be. The motivation is typically grounded in one or more problems that the organization faces, such as:

![]() The executive board does not see the value of having high-quality information.

The executive board does not see the value of having high-quality information.

![]() The organization thinks that it is doing a bad job in managing information quality and would like to know where and how to improve to help the business.

The organization thinks that it is doing a bad job in managing information quality and would like to know where and how to improve to help the business.

![]() The organization is worried that poor data is creating risks in a particular business unit and wants to know what to do to control or mitigate the risk.

The organization is worried that poor data is creating risks in a particular business unit and wants to know what to do to control or mitigate the risk.

![]() The organization recognizes that there are significant risks arising from poor information and aims to control them.

The organization recognizes that there are significant risks arising from poor information and aims to control them.

Once you have agreed on a common motivation, the next step is to formulate a brief mission statement that captures this motivation. An example could be:

Recognizing that information is a critical asset for our organization, we aim to achieve a full understanding of what information is, and how to control the risks that arise through poor information in our core business processes.

The mission statement can be used as an “elevator pitch,” the first sentence that is communicated to somebody who asks what the program is about. By embracing the mission statement, the senior executive shows his or her support for the TIRM program. It can also be helpful to set a common vision that you aim to achieve in the very long term.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

In a kickoff meeting, the call center management decides to formulate the following motivation for the application of the TIRM process in the organization:

Our vision is to provide every business process that has relevance for our client relationships with the optimal level of data and information quality.

A.1.2 Defining the goals of the TIRM process

Next, the goals for the process have to be determined. The goals should be derived from the motivation and in their way operationalize the mission statement and make it really actionable. A few examples of goals for the TIRM process are:

![]() “The goal of our TIRM program is to quantify the impact of poor data and information in our organization.”

“The goal of our TIRM program is to quantify the impact of poor data and information in our organization.”

![]() “The goal of our TIRM program is to improve information where it most impacts the time to delivery of our products.”

“The goal of our TIRM program is to improve information where it most impacts the time to delivery of our products.”

![]() “The goal of our TIRM program is to align IT investments with information needs in business processes.”

“The goal of our TIRM program is to align IT investments with information needs in business processes.”

![]() “The goal of our TIRM program is to optimize business process performance through focused information quality improvement.”

“The goal of our TIRM program is to optimize business process performance through focused information quality improvement.”

![]() “The goal of our TIRM program is to establish a risk register of all major risks that arise from information.”

“The goal of our TIRM program is to establish a risk register of all major risks that arise from information.”

![]() “The goal of our TIRM program is to remove redundant information processes.”

“The goal of our TIRM program is to remove redundant information processes.”

Note that there can be more than one goal for the application of the TIRM process. It really depends on what your organization aims to achieve. Of course, these goals should be realistic, achievable, and specific, and furthermore reflect the overall goals and values of the organization. They should also be prioritized to provide clarity where any conflicts arise.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The call center decides to focus on optimizing customer satisfaction and operational efficiency:

The goal of our TIRM program is to improve data and information where it impacts customer satisfaction and operational efficiency. We want to understand which data and information are critical for our key business processes and which data and information quality problems hurt the business most.

A.1.3 Defining the scope of the TIRM process

A clear scope should be defined for the TIRM initiative. The scope is dependent on the motivation and goals set for the TIRM process and on the resources that you are willing to invest.

At the outset it is important to define which parts of the business should be included in the scope. You might decide to permanently include only a particular business unit, product line, geographical site, etc., or you might implement the TIRM process in the entire organization. It really depends on the goals and the resources you have available for implementing the TIRM process. It also depends on how important information is regarded in your organization by senior leadership and how severe the known information quality issues are. If you have the resources and necessary support of your senior leaders, then the best strategy is to try the TIRM process in a small, but important part of the business, and then expand it gradually to the rest of the business. Bear in mind that the selection of business processes based on the scope that should be included in the analysis is made in step A3, when business processes are examined in more detail.

If the goal of the TIRM process application is to identify all information risks related to a particular part of your business, you might want to include all data and information assets that are used for the business processes in this business unit. This has the advantage that you do not miss out on data and information assets that are important for a business process but you have not thought about before.

If the goals of your process application are more tightly linked to particular IT systems, you can choose to focus on data and information assets in these IT systems. You can also decide to limit your analysis to, for instance, master data, transactional data, or other data types. So, it really depends on what your mission and goals are when you choose the scope regarding data and information assets.

Particularly, however, when the TIRM process is implemented with the goal of improving the effectiveness of IT systems and is, for instance, sponsored by the CIO or the business intelligence unit, it is easy to forget about data and information assets that are not stored and processed by IT systems. This is often not the best way to proceed, as omitting less structured information (e.g., that is shared via email and hardcopy documents or through personal communication) limits your view about which information is actually used in key business processes.

One example that we encountered in our work is that of an industrial engineer who telephones the planning department instead of looking directly at the planning data in the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system, because the planning information stored in the ERP system is hard to find and interpret. The planning department then looks up the information for the industrial engineer in the system, which is a waste of time and resources, and sometimes leads even to greater problems. The IT department would not be aware of these significant information quality problems if the role of unstructured information for the effectiveness of IT systems is downplayed and the actual usage of all types of data and information assets is not considered.

An important decision needs to be made regarding the information quality dimensions that you would like to focus on in the information risk assessment. We recommend you choose from the set of dimensions shown in Table 6.1. However, you can also define your own additional dimensions or use other information quality frameworks (e.g., Wang and Strong, 1996) that are relevant to the context in which the TIRM process is being applied.

Table 6.1

Standard Set of Information Quality Dimensions for TIRM

|

Information Quality Dimension |

Description |

|

Accuracy |

Is the data and information asset correct? Does it correspond to the real value that it represents? |

|

Completeness |

Is the data and information asset complete? Does it contain all the information it should contain? |

|

Consistency |

Is the information stored in a consistent format? |

|

Up to date |

Has information changed since the last time it was been updated in a way that it is incorrect now? |

|

Interpretability |

Is the content of the data and information asset easily interpretable by the users? Is it represented in a way that is easy to understand? |

|

Accessibility |

Can I access the data and information asset in a timely manner? |

|

Availability |

Is the information that I need available in my organization? |

|

Security |

Can somebody else access the information who should not be able to access it? How likely is it that the information gets lost? |

Choosing information quality dimensions at this stage can be a bit tricky. How do you know beforehand which problems are the greatest? It is easy if the goal of your TIRM initiative specifies particular information quality dimensions explicitly or implicitly. But even then, you probably need to clearly state which information quality dimensions are included or excluded from the analysis. For example, if the goal of the TIRM process is to identify the risks that arise from incorrect information, you have to decide if this includes just the accuracy dimension, or should it also include the completeness and up-to-date dimensions. If you are not sure, the safest option is to go with the standard set of information quality dimensions for the TIRM process shown in Table 6.1. You could also decide to exclude the security dimension from this list, if you only want to focus on risks that arise through information usage. Please bear in mind that the selection of information quality dimensions is only preliminary at this stage, and will be potentially refined in step A5 and during information risk assessment in stage B.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The call center decides to focus on the part of the business that has direct contact with end customers. It is also decided to include all types of data and information assets that are important for the business processes in the scope. The information quality dimensions to be included are accuracy, completeness, consistency, up to date, interpretability, accessibility, and availability. The security dimension is put out of scope since information security is satisfyingly managed within the organization.

A.1.4 Defining the responsibilities for the TIRM process

Once you have defined a scope for the TIRM process application, it is time to identify the roles and responsibilities involved in the execution/performance of the process. The detailed organizational setting is discussed in Chapter 9. The following roles and responsibilities have to be undertaken by adequately capable representatives who should be suitable with regards to the chosen scope and goals of the TIRM process initiative.

ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

TIRM Process Sponsor

The TIRM process sponsor is in charge and is responsible for making available the necessary resources to implement the process and is interested in the results. This should be an executive or a very senior manager who has budget responsibility.

TIRM Process Manager

The TIRM process manager manages the resources and is responsible for the implementation of the process. A senior- or middle-level manager should undertake this role.

TIRM Process Facilitator(s)

The TIRM process facilitator organizes and facilitates the workshops. This can be a middle- or lower-level manager or consultant. If the scope is large, several process facilitators might be necessary.

Business Process Representatives (chosen in step A3)

For each business process in the scope, one to two subject-matter experts should be chosen who have a good knowledge of the business process they represent.

IT System and Database Representatives (chosen in step A5)

For each IT system and database in the scope, a representative should be chosen who has good knowledge of the IT system and/or database and of the data and information assets that are related to the IT system and/or database.

As a rule of thumb, the larger the scope of the application, the more human resources are required and the higher up the TIRM process sponsor should be (in the organizational hierarchy). This is appropriate because the sponsor needs to have the seniority and authority to provide both the budget and support needed. The process manager has the task of overseeing and coordinating the application of the TIRM process, but does not need to do this full time. In some cases, the TIRM process sponsor might also act as the process manager. The process facilitators support the operationalization of the TIRM process “on the ground.” They help to run the workshops, undertake analysis and evaluation, and produce reports for the TIRM process manager, the TIRM sponsor, and the rest of the organization. They need to read this book and should also be experienced in the discipline of information management in general. They are also responsible for coordinating the business process representatives and IT representatives.

Business process representatives are subject-matter experts in a particular business process in the scope. If you have many smaller business processes, it might be sufficient to have just one business process representative for each business process. For larger business processes (with many parties involved and many different activities), more business process representatives could be selected, since one business process representative might not have the full oversight over the business process. Bear in mind that if there are different departments involved in one business process, it would make sense to choose one business process representative from each of the departments.

The IT representatives should jointly have a good oversight of the IT landscape and all important applications and databases in the scope of the process. They should be experienced in IT project management. None of these roles and responsibilities necessarily requires a full-time commitment (the TIRM team is likely to be full time while the business stakeholders are not) but this, again, depends on the scope of the application. In medium-size businesses or if the scope is limited to a handful of business processes, it can be done as a side activity in addition to the normal day-to-day job. But, of course, it will always require a significant time commitment by the actors who fill out the roles for the TIRM process. The structure of different committees who are ultimately responsible for the TIRM process is introduced and debated in Chapter 9.

![]() ACTION TIP

ACTION TIP

When you try to find suitable people to fulfill the different roles required for the TIRM process, excitement and interest of the employees about data and information assets is as important as their expertise.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

At the call center, the data quality manager convinces the managing director of the call center to become the sponsor of the TIRM program and offers himself as the TIRM manager and facilitator. Two data enthusiasts from the IT department volunteer to become the IT and data representatives, and together they cover all major IT systems. Finally, the managing director chooses two business process representatives for each business process.

A.1.5 Defining the context of the TIRM process

Finally, the context of the process itself needs to be defined—that is, how the TIRM process should be integrated within the organization. In particular, the relationships to other programs or projects that are interrelated have to be defined. This is covered in more detail in Chapter 9.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The TIRM initiative at the call center is run as an executive-sponsored business performance improvement program and reports directly to the management board. The recommendations should be presented to an information governance council, which is headed by the corporate operation officer.

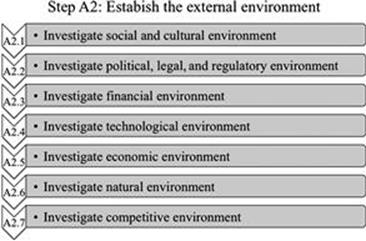

Step A2: Establish the external environment

In this step, the external environment of the organization needs to be established (Figure 6.4). This can include aspects ranging from social and cultural, political, legal, regulatory, financial, technological, economic, natural, and the competitive environment, whether international, national, regional, or local (International Organization for Standardization, 2009, p. 31000).

FIGURE 6.4 Step A2 in context.

Risk management, in general, requires a good understanding of the context of the organization, both internal and external. The external environment has a significant influence on the success of every organization. Therefore, organizational behavior is often geared toward the external environment. It sets requirements and necessities for the organization. Information is often essential to comply with these requirements and necessities. For example, financial information often needs to be submitted to regulators, which is a requirement that comes from the external environment of your organization. If the customers in your specific market require customized support and a high level of service, this sets higher demands for your customer information management. There are many other examples to demonstrate the interplay between the external environment and information management. This step will, therefore, help to assess and treat information risk in the succeeding stages. The external environment of an organization can have a major influence on how information risks are evaluated.

![]() EXAMPLE

EXAMPLE

A publicly listed company A has to comply with different financial requirements and rules than the privately owned family business B. Accounting information that is 10% inaccurate can lead directly to huge penalties by financial regulators in the case of company A, but might pose only minor risks in the case of company B.

![]() EXAMPLE

EXAMPLE

The U.K. utility industry is a sector that is heavily regulated with regard to price and service quality. Information about the age and reliability of physical assets plays a crucial role as evidence that investments to modernize the assets are really necessary, which is important to justify the increase in prices.

The focus should be on aspects of the external environment that are relevant and significant for the scope set in step A1—that is, the business processes and data and information assets. Every organization will have other external factors that are important. The art is to identify the most relevant drivers in the external environment. Brainstorming can be used as a creative technique (see Chapter 11). As shown in Figure 6.5, the external environment can cover a very wide range of aspects, including social and cultural, political, legal, regulatory, financial, technological, economic, natural, and the competitive environment, whether international, national, regional, or local.

![]() ACTION TIP

ACTION TIP

Every organization will have other external factors that are important. The art is to identify the most relevant drivers in the external environment. Brainstorming can be used as a creative technique (see Chapter 11).

FIGURE 6.5 Activities in step A2.

A.2.1 Investigate social and cultural environment

The social and cultural environment can play an important role for your organization. For example, if you are selling products to consumers or other companies, it depends on the social and cultural background of the customers as to how the behavior of your organization is perceived. For example, in some countries, corruption and unethical behavior is more tolerated than in others (Rose-Ackerman, 1999). Customers (either consumers or business customers) might stop buying your products if they perceive your organization as unethical. This does not necessarily mean being involved in corrupt activity. For some, it might be enough that your company harms the environment and ecological systems in some way. Or, that your organization obtains its supplies from suppliers that are not perceived to respect human rights. For instance, the consumer products giant Apple has been heavily criticized for the working conditions at Foxconn; Samsung has also been criticized for excessive overtime and fines for employees in China. Sometimes, you can get penalized by the society (consumers and/or the government) when you move parts of your production away from the country (France would be a typical example; see Trumbull, 2006). Thus, the way you market your products will be heavily dependent on the cultural and social background of your customers.

A.2.2 Investigate political, legal, and regulatory environment

The political, legal, and regulatory environment can be very influential insofar as the way you carry out business activities. Organizations need to comply with each country’s laws and regulations in which they do business. Rules and regulations can change frequently and are often ambiguous; they also depend on the political culture in a country. Many industries are heavily regulated around the world, such as banking and finance, utility, transportation, oil and gas, and mining. The regulations will have a major influence on your business model. Moreover, the legal system can differ from one country to the other (e.g., civil law, common law, religious law) and often requires very specialized expertise. The introduction of new taxation laws can change the basis of your investment decisions. Furthermore, in some countries, it might be more difficult for you to protect your organization’s intellectual property. A more extreme example is if the countries in which you undertake business get involved in conflicts, such as war, civil war, and revolutions—these can completely invalidate what initially were very sound business decisions.

A.2.3 Investigate financial environment

The financial environment affects how an organization can raise finance, transfer risk, trade financial securities, allow international trading in different currencies, and share profits with its investors. It can include many different markets, such as commodities, real estate, bonds, cash, and many others. In many ways, the success of an organization is dependent on the financial environment. For example, if it is easier and cheaper to access money, a company is more flexible in undertaking investments. Lower borrowing rates can offer a substantial competitive advantage. For many organizations, the ability to get access to money is crucial for their survival.

A.2.4 Investigate technological environment

Technology is a key driver for innovation in many markets. Disruptions in technology can often be game-changers. Kodak, a company founded in 1889 that popularized modern photography, had to file for bankruptcy in 2012 because of its tardiness in transitioning to digital photography (ironically, it invented digital photography). Technology is important not only in engineering industries. For instance, computers revolutionized investment banking as they allowed traders to automatically and almost instantaneously react to changes in the market. Whatever technologies drive your particular market, it is important to remain cognizant of new developments, as technologies can change very quickly.

A.2.5 Investigate economic environment

Businessdictionary.com defines the economic environment as “the totality of economic factors, such as employment, income, inflation, interest rates, productivity, and wealth that influence the buying behavior of consumers and institutions.” The economic environment is, of course, important for commercial corporations, however, the economic environment is also important for nonprofit organizations because they are dependent on the financial health of the population (private individuals and institutions) to attract donations and income.

A.2.6 Investigate natural environment

Natural disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions can disrupt the functioning of many organizations, for instance, by interrupting the supply chain of a company. Sectors such as insurance and banking can be directly affected by large-scale natural disasters. Moreover, natural resources are important in many industries.

A.2.7 Investigate competitive environment

Not every industry is equally competitive. Every industry and market will have its particular demands and challenges. Acting as a monopoly can be a blessing for profit margins, but it can also mean that the regulatory control is likely to be tighter. In highly competitive fast-moving markets, price competitiveness and large research and development costs can lead to very low margins. The manner in which your organization conducts business will be heavily dependent on the competitive environment it is exposed to.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The call center has to respect the cultural and social norms of the country from which the end customers are calling. Also, rules about data protection differ from country to country. With many players penetrating the market, business is becoming increasingly competitive.

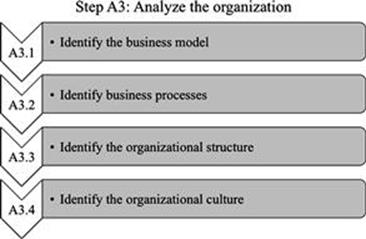

Step A3: Analyze the organization

After having established the external context of your organization, it is time to have a closer look at the organization itself (Figure 6.6). Understanding the business model, business processes, organizational structure, and culture are all important elements in understanding the internal environment for information management (Buchanan and Gibb, 1998). These activities feature in step A3 as shown in Figure 6.7.

FIGURE 6.6 Step A3 in context.

FIGURE 6.7 Activities in step A3.

A.3.1 Identify the business model

A good place to start is to take a look at the business model. Most organizations will have a carefully developed business model, which all staff should have an awareness of.

Consider what is it that your organization is actually doing? What kind of capabilities has your organization built up to do these things? How is it creating value for its customers? And if your organization has competitors, what is it that makes your organization competitively special? Business strategy is about utilizing the unique internal capabilities to best fit them to the opportunities and requirements of the market. So, what kind of business strategy is your organization pursuing?

If your organization is nonprofit, there is still some kind of business model. A charity must still often compete against others, for example, to raise money and attract donations. A governmental organization has (hopefully) a reason to exist by providing some sort of value to the taxpayers. Even a church can have a business model (although it probably would not call it so by name), as it needs to operate with limited resources and usually aims to provide high-quality services to its congregation.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The call center is a regional market leader in the premium segment of call center services. It offers inbound and outbound outsourcing services for large corporations that, on the one hand, have high volumes of telephone calls, and on the other hand, require very high-quality responses. The call center’s main points of competitive advantage are rigorous processes and careful selection and training of human resources to ensure high quality at large volumes.

A.3.2 Identify business processes

Business processes need to be identified and included in the scope. Information creates risk since it is used in business processes in the organization. Your business model explains what your organization is doing. Examining the key business processes in your organization will give insight into how your organization is implementing its business model.

Remember to focus only on identifying business processes that are in the scope of the TIRM process outlined in step A1. If you are not fully aware of your key business processes in the scope, you will be able to identify them by examining your business model and the key activities that deliver value in line with it.

![]() ATTENTION

ATTENTION

Avoid wasting time. Focus only on identifying business processes that are in the scope of the TIRM process outlined in step A1.

In general terms, there are four different types of business processes (Earl and Khan, 1994):

![]() Core processes (servicing external customers)

Core processes (servicing external customers)

![]() Support processes (servicing internal customers)

Support processes (servicing internal customers)

![]() Business network processes (crossing company boundaries)

Business network processes (crossing company boundaries)

![]() Management processes (establishing the strategic framework for the other processes)

Management processes (establishing the strategic framework for the other processes)

Each type of business process is explained further in the following box.

![]() THEORETICAL EXCURSION

THEORETICAL EXCURSION

As a general rule, there are four different types of business processes:

![]() Core processes, also called operational processes, execute the tasks that deliver value to the customers.

Core processes, also called operational processes, execute the tasks that deliver value to the customers.

![]() Supporting processes support the core processes, and only indirectly contribute to providing customer value.

Supporting processes support the core processes, and only indirectly contribute to providing customer value.

![]() Business network processes go beyond the boundary of an organization. Often, value is delivered through collaboration with other external entities through business network processes. The supply chain is a good example.

Business network processes go beyond the boundary of an organization. Often, value is delivered through collaboration with other external entities through business network processes. The supply chain is a good example.

![]() Management processes make decisions on which, how, when, and to what extent core processes are executed, as well as by whom. Also, on how they should be orchestrated to deliver value—this is done through administration, allocation, and control of resources. Thus, management processes are the steering wheel of an organization.

Management processes make decisions on which, how, when, and to what extent core processes are executed, as well as by whom. Also, on how they should be orchestrated to deliver value—this is done through administration, allocation, and control of resources. Thus, management processes are the steering wheel of an organization.

In each category of business processes, there are some that are more important than others. Once business processes have been identified, the most relevant ones are selected. They can be ranked according to their criticality and importance in the business model. The selection should take the motivation and goals for the TIRM process into account, as set out in step A1. It is essential that senior management is involved in some form in this ranking and prioritization process and gives approval, for example, by participating in a workshop or by simply reviewing and suggesting corrections to the ranked list of business processes once it is created.

Additionally, collect the documentation that is available in your organization about the selected business processes. It is very likely that your organization has previously modeled some business processes. In many instances it will be possible for you to reuse documents that already exist in your organization. Make sure, however, that the business process models are up to date.

![]() ACTION TIP

ACTION TIP

There are many different types of modeling and visualization techniques that can be used to model these processes, such as use-case diagrams, activity diagrams, event-driven process chains, and many more. Any models of business processes are good enough for the purpose of the TIRM process, as long as they get acceptance in your organization.

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

Most organizations have models of their important business processes. Make sure you collect the documented models.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The call center identifies three core business processes in the scope, which should be in the focus:

1. The customer inquiry response process, which deals with end customer requests of the client company that has outsourced the support function to the call center.

2. The product sales process where the call center contacts potential end customers on behalf of the client company to sell their products.

3. The customer survey process, which executes predefined customer surveys with end customers on behalf of the client company.

Other types of business processes should not be considered at the initial implementation of the TIRM process.

A.3.3 Identify the organizational structure

Next, the organizational structure relevant to the chosen scope in A1 is identified. The organizational structure is usually documented in existing diagrams. The organizational structure should be analyzed to identify relevant insights for information management. For example, an organization’s structure that is not well aligned to business processes can lead to functional silos, which prevent information from flowing optimally throughout the business processes.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The call center is divided into two departments: inbound and outbound. The inbound department is responsible for taking care of incoming customer calls for the client. The outbound department deals with calls that are actively made, for example, to sell client products to end customers or to conduct surveys.

A.3.4 Identify the organizational culture

Organizational culture is always important for organizational success and every organization has its own distinct culture. To manage information risks, you have to understand the culture in the particular organization, then adapt and choose the methods that you are using for assessing and treating information risks so that it really fits with the organizational culture.

According to Buchanan and Gibb (1998), there are two different approaches to identify organizational culture:

![]() Stakeholder analysis (Grundy, 1993)

Stakeholder analysis (Grundy, 1993)

![]() Force-field analysis (Lewin, 1947)

Force-field analysis (Lewin, 1947)

While stakeholder analysis helps to diagnose key stakeholder influences on the information strategy, Lewin’s force-field analysis identifies the enabling and restraining forces that affect the information strategy. However, you do not need to analyze organizational culture with formal methods. The easiest way is to keep your eyes and ears open when you talk to people and try to identify cultural patterns. Keep these cultural patterns and characteristics in mind when you conduct the information risk assessment and treatment and whenever you communicate and consult with stakeholders as part of the TIRM program.

![]() ACTION TIP

ACTION TIP

The acceptance of different methods for business process modeling differs from one organization to another. Aim to understand the culture and adapt the choice of methods and techniques to it. Make sure you communicate in an appropriate language, one that not only the stakeholders speak but also that reflects their culture.

Finally, the attitude toward information and its perceived value is an important element of organizational culture for information management and should be investigated during interviews with employees and managers.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The culture in the inbound department is very cooperative and therefore information is freely shared whenever needed. As call center representatives often get rewarded on the basis of the level of their individual sales performance in the outbound department, the culture there is less collaborative with call center representatives being less eager to help each other and share information and knowledge.

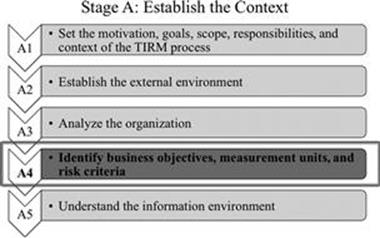

Step A4: Identifying business objectives, measurement units, and risk criteria

Risk is the effect of uncertainty on the objectives of an organization (Figure 6.8). To manage the uncertainty you have to identify your organization’s business objectives and appropriate ways to measure how each is being achieved or not. Moreover, you need to define what the different points in the measurement scales actually mean to your organization by setting risk criteria. Figure 6.9 shows the associated activities of step A4.

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

Without identifying business objectives and ways to measure the achievement objectives, it is not possible to assess risk.

FIGURE 6.8 Step A4 in context.

FIGURE 6.9 Activities in step A4.

A.4.1 Identify business objectives

Business objectives are the goals that an organization aims to achieve and the organization’s leadership sets them. They are often described in the organization’s mission statement—in such cases, it is appropriate to start the identification of business objectives by extracting the goals articulated in the mission statement.

The business objectives should be classified into distinct categories, such as health and safety or revenues. However, the mission statement might not accurately reflect the goals and targets set by the leadership. Therefore, it is important that the business objectives, which have been identified, are reviewed and refined by senior management.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The mission document of the call center states three different goals.

Our company is united in three goals that are guiding us throughout all parts of our business:

1. Our goal is to have sustainable sales growth.

2. Our goal is to always operate in a cost-efficient manner.

3. Our goal is to always satisfy our customers to the fullest possible extent.

Based on the goals in the corporate mission, the TIRM steering committee identifies three categories of business objectives:

1. Sales growth

2. Operational efficiency

3. Customer satisfaction

A.4.2 Identify measurement units for impact on business objectives

A metric to measure impact needs to be defined for each business objective. You should start by identifying measurement scales that are already in use in your organization. For some of the business objectives, there will probably be some, but it may take some effort to find them. Measurement scales will have to be defined if there is no measurement scale already available.

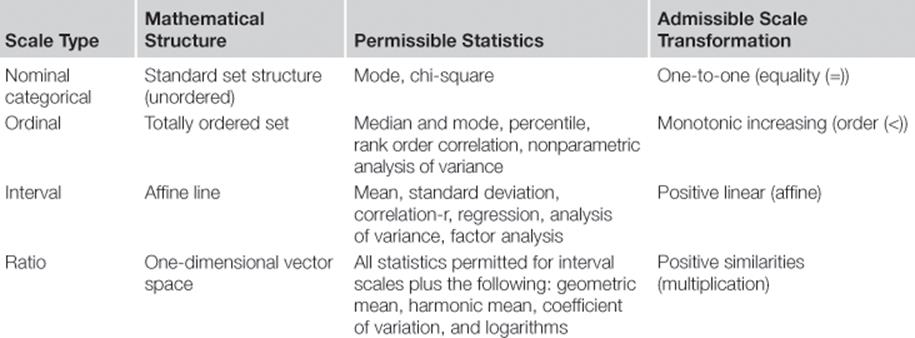

To be able to make all statistical calculations needed for calculating the total risk figures, the measurement metric needs to be at least an interval scale (see “Theoretical Excursion” box for an introduction to the different types of measurement scales). For the purposes of the TIRM process, a nominal scale would not be sufficient, as risk values would not be comparable. You simply cannot say if one value is worse or better than another value on a nominal scale. Since risk is calculated as the product of the impact multiplied by the probability, an ordinal scale is also unsuitable, because this calculation would not be meaningful. Take the example of a three-point scale: small damage, medium damage, and big damage. If there is a 30% probability of medium damage, it is not possible to multiply these to calculate the expected average value.

![]() IMPORTANT

IMPORTANT

Measurement metrics that are used as part of the TIRM process should preferably be interval scales or ratio scales if you want to quantify and calculate risk as an output of the TIRM process.

![]() THEORETICAL EXCURSION

THEORETICAL EXCURSION

Over more than half a century ago, Harvard psychologist Stanley Smith Stevens published an article on the theory of scale types in the prestigious Science Journal (Stevens, 1946), which is still, to this day, the most dominant work on measurement scales. His theory proposed that there are four different types of measurement metrics (Table 6.2).

Table 6.2

Four Different Types of Measurement Metrics

Source: Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Level_of_measurement.

The first type of scale is called nominal or categorical, which is an unordered set of qualitative values. An example would be the categories male or female, for which you cannot say which of the values is bigger; therefore, it is unordered. Another example could be a list of colors (e.g., red, gray, yellow, or blue). The only statistics that you can do on a nominal scale is to calculate a mode, which is the value that appears most often, and the chi-square to check if there are any correlations between the values. There is no transformation allowed on this scale.

The second type of scale is called ordinal, which is a totally ordered set of qualitative values. This could be, using a simple example, the scale consisting of three age values: young, middle aged, and old. You can assign an ordered rank to each value, for example, 1 is young, 2 is middle aged, and 3 is old. A higher number equals an older age, but there are only three possible values in the data set. If you multiply these with any number, the ordering of the values will stay intact. Let’s say in our example we multiply by 5 the numbers that represent our three values; the rank of each attribute will still stay the same—that is, 5 is young, 10 is middle aged, and 15 is old. In such scale, it is possible to calculate the most common value (mode), and additionally the middle-ranked item, the so-called median. However, as you cannot, for instance, say on this type of scale how much older an “old” person is compared to a “young” person, the differences and sums cannot be calculated. It follows that it is not possible to calculate the average value (also called the mean).

The third type of scale is called interval, which is an ordered quantitative scale that allows positive linear transformations. An interval scale is similar to the ordinal scale ordered, but additionally, it tells us about the size of the intervals between data points. For those readers who like mathematics, you can do the following transformation of all data points x without changing the meaning: y(x) = a × x + b with a and b being any real numbers. A commonly used example is the Celsius temperature scale. For this scale, it is permissible to perform many more statistical operations, such as the mean (the average value), the standard deviation (how far values are scattered around the average), linear correlation, regression, analysis of variance, and factor analysis.

Finally, the fourth type of scale is called the ratio, which in addition to having the attributes of an interval scale has a true zero point. Using the example of the temperature as before, it would only be the Kelvin temperature scale that fulfills this criterion, as it has a true zero point. This type of scale allows additional statistical operations, such as the geometric and harmonic mean, and the coefficient of variation and logarithmical transformations.

An example of a self-defined scale for the TIRM process is shown in Table 6.3. If you define a scale of your own for one or more impact domains, you should give examples of what a value actually means.

Table 6.3

Example of a Self-defined Measurement Metric

|

Point scale |

Interpretation |

Examples for Health and Safety |

|

0 |

No impact |

No impact. |

|

0 < x < 1 |

Very minor impact |

Potential minor injury. Potential minor impact on health and safety of employees, customers, society, etc. |

|

1 < x < 10 |

Minor impact |

One minor injury. Minor noncompliance to health and safety laws. Minor impact on health and safety of employees, customers, society, etc. |

|

10 < x < 100 |

Medium impact |

Several minor injuries. One near miss. Medium impact on health and safety of employees, customers, society, etc. |

|

100 < x < 1000 |

High impact |

One severe injury. Severe noncompliance to health and safety laws. High impact on health and safety of employees, customers, society, etc. |

|

1000 < x < 10,000 |

Very high impact |

One casualty. Very high impact on health of employees, customers, society, etc. |

|

x > 10,000 |

Extreme impact |

Several casualties in accident. Extreme impact on health and safety of employees, customers, society, etc. |

In some cases, it could also be useful for estimating the impact in stage B to define measurement metrics as the product of the impact per unit multiplied by the number of units. For example, instead of saying that a flooding event creates an impact of $1,000,000 damage, the impact per square meter is given (e.g., USD $10,000) and then the number of square meters that are affected by the flood needs only to be estimated (e.g., 100 square meters), which is then used to calculate the impact ($10,000 × 100 m2 = $1,000,000).

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The TIRM steering committee chooses the following measurement metrics for the three business objectives:

1. Sales growth impact is measured as lost sales revenues in U.S. dollars.

2. Operational efficiency is measured as increased operational costs in U.S. dollars.

3. Customer satisfaction is measured using the number of unsatisfied callers; this metric can be measured using surveys with end customers conducted at the end of a telephone call, and considering also the number of active customer complaints.

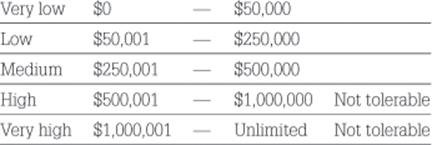

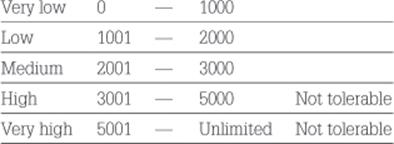

A.4.3 Define risk criteria

Finally, the risk criteria need to be defined for TIRM. Risk criteria make sure that the risk appetite of your organization is considered during risk evaluation. Losing $1,000,000 in sales can be a pretty bad thing for, let’s say, a medium-size furniture manufacturing company, but is not such a significant risk for a gigantic retailer like Wal-Mart. Risk criteria are therefore needed as “the terms of reference against which the significance of a risk […] is evaluated” (ISO, 2009, p. 6). They are “based on organizational objectives, and external and internal context” and can be “derived from standards, laws, policies, and other requirements” (ISO, 2009, p. 6).

Risk criteria include the level at which a risk becomes acceptable or tolerable (e.g., a monetary value), the way likelihood is defined (which follows the way in which likelihood is defined in the model), and the timeframe that should be considered.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The TIRM steering committee chooses the following risk criteria in a one-year timeframe:

The following are the risk criteria for business objectives of sales growth and operational efficiency measured in yearly lost revenue in USD and yearly higher operational costs in USD.

The following are the risk criteria for the business objective of customer satisfaction measured in the number of dissatisfied callers.

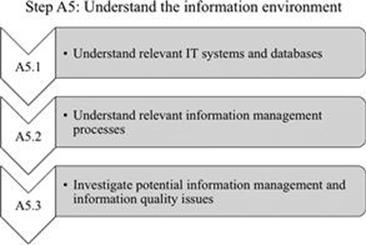

Step A.5: Understand the information environment

The aim of this step is to gain a better understanding of the information environment, which focuses on the following aspects: information management processes, IT systems, and known data issues in the scope (Figure 6.10).

FIGURE 6.10 Step A5 in context.

Depending on the scope and goals of the TIRM process, some aspects of the information environment might require more attention than others. It is recommended that you follow the three activities shown in Figure 6.11 and to add further activities based on your own judgment of your organization’s situation.

FIGURE 6.11 Activities in step A5.

A.5.1 Understand relevant IT systems and databases

This activity is really about gaining a better understanding of the IT systems and databases that collect, store, and process the data and information assets that are in the scope of the TIRM process.

You can start this activity by creating a list of IT systems and databases that are relevant for the scope (defined in A1.3). This is not always as straightforward as it might sound, mainly because of two reasons. In many organizations a complete and up-to-date register of IT systems and databases does not exist or is difficult to get ahold of. Moreover, you need to find out which IT systems and databases in your organization are actually relevant for the scope of the TIRM process. For some it will be obvious, but for others it will be a bit more difficult. Which data and information assets are needed for business processes in the scope will be analyzed later in stage B, thus is not appropriate at this stage.

Once an initial list of relevant IT systems and databases is created, you should gather information that helps you understand each of the relevant IT systems and databases. For each IT system and database, a representative should be identified and chosen who is a subject-matter expert and who will be incumbent to share the knowledge about a particular IT system and/or database throughout the application of the TIRM process. Any relevant documentation, such as IT system architecture, data models, information flow diagrams, etc., should be collected. Moreover, a demonstration of important software applications should be organized in this substep, because it makes it easier to facilitate the information risk assessment workshops in stage B and allows for a better understanding of information usage problems related to a particular IT system or database. You should also investigate how IT systems and databases are interlinked with each other.

Linking your TIRM program to an enterprise architecture model can help you get stronger senior management support (see the following box). It can also make it easier to identify suitable information risk treatment options in stage C.

![]() THEORETICAL EXCURSION: ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

THEORETICAL EXCURSION: ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

The best overview of what and how an organization does is a model of an enterprise architecture, which is defined by the MIT Center for Information Systems Research as “the organizing logic for business processes and IT infrastructure reflecting the integration and standardization requirements of the company’s operating model. The operating model is the desired state of business process integration and business process standardization for delivering goods and services to customers” (Weill, 2007).

Enterprise architecture is a bird’s eye view of the enterprise, which shows strategic objectives, business processes, organizational structure, IT landscape, databases all at one glance, and puts a context to it. Two commonly used models for enterprise architecture are Zachman and TOGAF (Zachman, 1987; Harrison, 2007). An important part of the enterprise architecture is the information architecture, which is “the art and science of organizing and labeling data including: websites, intranets, online communities, software, books, and other mediums of information, to develop usability and structural aesthetics” (Information Architecture Institute, 2013).

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

The TIRM process manager together with the TIRM facilitators organize meetings with IT managers, data managers, and information architects to identify the most important IT systems in the scope, which are used for all three core processes:

1. Computer Telephony Integration System (CTI), which enables autodials by using the customer contact information from the database and automatically helps to comply with country-specific call periods. It also brings up basic information about the caller and the history of interactions with the caller. The system also allows the running of automatic call feedback surveys with customers on the telephone; these can evaluate how good the service provided by the call center agent was.

2. Knowledge Base System (KBS), which is a knowledge base of frequent problems and questions with potential solutions. Subject-matter experts are identified who can be contacted for second-level support.

3. Issue Tracking System (ITS), which allows the call center agents to record issues that are reported by customers and to manage these issues. The system is connected to the CTI, which allows the CTI to show issues recorded in the past with a customer automatically on the screen. The KBS feeds automatic suggestions about how to resolve an issue that is recorded in the ITS.

4. Customer Relationship Management System (CRM), which manages customer data and tracks and supports sales activities. The system feeds data into the CTI and the records are connected with issues tracked in the ITS.

Moreover, there are three main databases within the scope of the TIRM process identified that support the IT systems:

1. The customer master database contains all end customer–related information, such as contact details, date of birth, and any other master data. It supports mainly the CTI and CRM.

2. The customer interaction database contains transactional data from interactions with end customers, including issues that are reported by customers and also any feedback that is given in automatic surveys with customers after a call. The database is used for the ITS and CTI systems.

3. The expert database is a data warehouse that contains the data about answers and solutions to frequent problems and that feeds into the KBS.

For each IT system and database, relevant documents are identified during the initial meeting and are shared with the TIRM stakeholders. For each IT system and database, a subject-matter expert is chosen to be the IT system and database representative.

A.5.2 Understand relevant information management processes

Information management processes handle data and information assets as they are created, organized, stored, processed, accessed, used, archived, or deleted. As part of this activity, you should identify key information management processes that are relevant for the scope of the TIRM process. This can be done by interviewing information managers in the organization. Documents about at least some of the information management processes can be found in many organizations, so they are worth investigating.

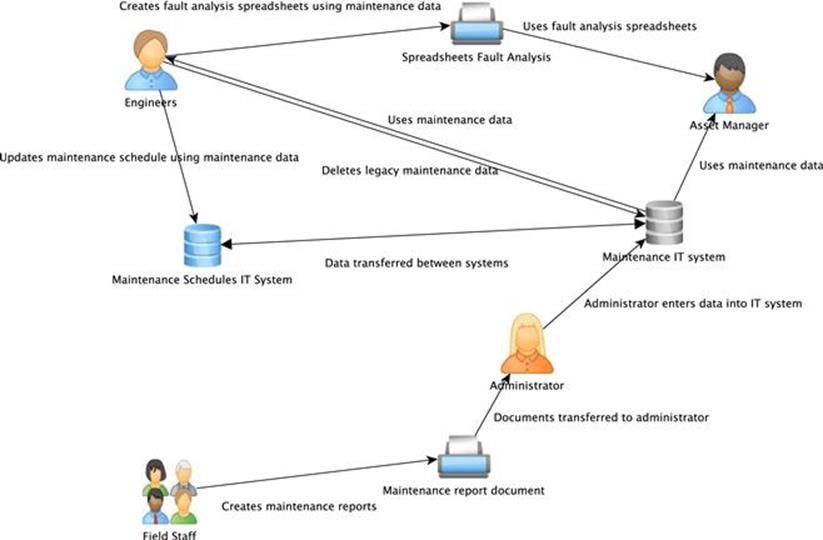

Another method that can help you understand the information management processes is to model how information flows throughout the enterprise over the information life cycle. It should show each significant step when information is created, collected, processed, transferred, stored, accessed, used, maintained, and deleted, and also describe who or what system and database is involved in the step. An example of an information flow diagram is shown in Figure 6.12. For instance, the field staff creates a maintenance report, which is entered into the maintenance IT system by an administrator and then used by engineers and the asset manager.

FIGURE 6.12 Example of an information flow diagram.

Another method that can help you understand the information management processes are so-called information management maturity models, which give an overview of information management process capabilities in the organization (see following box).

![]() THEORETICAL EXCURSION: MEASURING THE MATURITY OF INFORMATION MANAGEMENT

THEORETICAL EXCURSION: MEASURING THE MATURITY OF INFORMATION MANAGEMENT

Information management maturity models can help identify weaknesses in the information management processes in an organization. A maturity model is used to assess capabilities by evaluating the maturity of processes and to identify priority areas for improvement. A typical model consists of five maturity levels: initial (level 1), repeatable (level 2), defined (level 3), managed (level 4), and optimizing (level 5), although levels are sometimes named differently. Within these models, each maturity level is based on a comprehensive set of criteria of information management; these comprise concept, function, behavioral aspects, requirements to be met, and measurement.

To assess maturity, for each level and criteria evidence is collected for analysis, reflection, and synthesis. Measurement of both quantitative and qualitative factors is used that includes a defined process for building the outcomes from each level to monitor progress, and to take corrective actions at each level when necessary. Increased maturity evolves then through a progression of levels or stages with transformations over time. Both the assessment of maturity levels and the understanding of how to attain higher levels of maturity are central to increasing the maturity level of an organization.

An example of a maturity model for information management is the IT–Capability Maturity Framework (IT–CMF, see http://ivi.nuim.ie/it-cmf). Based on capabilities and categories along 32 critical processes, this framework is designed as a systematic framework that enables senior management and chief executives to interrogate, understand, and improve an organization’s maturity, thus ensuring realization of IT capabilities and optimal delivery of business value from IT investments.

![]() ATTENTION

ATTENTION

Information management maturity models will compare your processes with current good practices and tell you how well (or otherwise) you comply with them. However, every organization is different! Maturity models do not show you which improvements will bring about the most value in the context of your organization.

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

Together with a TIRM facilitator, the IT system and database representatives analyze and document the fundamental information management processes for the IT system and databases they represent. This can be summarized as:

1. Data in the customer master database is initially obtained from the client company and then updated by the call center agents. Customer data has to be deleted when a client company decides to stop using the services of the call center.

2. Data in the customer interaction database is automatically recorded during interactions with end customers. The call center agents enter issues raised by customers into the system. The data comes from the ITS and CTI systems.

3. The data in the expert database is generated and updated manually by a working group of team leaders and business analysts who go through the most frequently faced issues on a monthly basis, by analyzing data from the customer interaction and customer master databases.

The TIRM facilitator and the IT system and database representatives also create an information flow map, a sample of which is shown in Figure 6.13.

FIGURE 6.13 Sample information flow diagram for call center.

A.5.3 Investigate potential information management and information quality issues

This activity investigates general information management and information quality issues that can potentially lead to information quality problems in the business processes. It is the first part of a data and information quality assessment in the scope of the TIRM process, which is done from an information manager’s perspective. The results of this activity will be used in step B3 to help identify data and information quality problems in the most important business processes from an information user perspective. They can also be used later to identify the causes of information quality problems in step C1.

First, it is appropriate to note any general information management issues that might potentially lead to information quality problems; this can be done by interviewing IT representatives—for example, you might identify a general awareness of a data entry process that is not being executed as well as it should be. Some of the problems might have already been identified during the earlier activities undertaken in substeps A.5.1 and A.5.2. Interviewing data and information managers may identify some other issues. The identified issues should be documented in a list, which should include a detailed description of the problems.

Second, known issues with the quality of data and information assets themselves should also be documented independent of the actual usage of the data and information assets—for example, many data fields in a table are empty or data is captured with many typing errors. There might already be software tools running to profile and check data (see Chapter 12 for an introduction and overview of how software tools can help you). If data profiling results relevant for the scope are easily available, they should be analyzed and documented.

![]() ATTENTION

ATTENTION

Be aware that data quality software tools (e.g., for data profiling) can only identify a small fraction of data and information quality problems!

![]() EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

EXAMPLE: TIRM PROCESS APPLIED AT A CALL CENTER

By interviewing information managers for each IT system and database in the scope of the TIRM process, a number of general information management issues could be identified:

1. Call center agents often leave data fields empty.

2. Call center agents fill data fields with default values instead of the accurate values to reduce the amount of work they have to do.

3. Call center agents make spelling errors when they enter new customer master data.

4. Call center agents do not spend enough time describing the solution to an issue when a customer issue has been resolved.

5. The customer data that is provided by the client company is often in an incompatible format and needs transformation, which sometimes leads to problems.

6. The knowledge base is populated manually by the team leaders and business analysts; they include the keywords but often miss out the recording of some relevant information that exists. It could be more analytically driven.

A data profiling software tool is applied to the three databases—customer master, customer interaction, and expert—that reveals many data quality issues, such as:

1. There are many duplicate customer records.

2. Many fields that can be used to describe an issue reported by a customer contain null values, blank fields, or invalid values (descriptions that have less than three words).

3. Data on potential subject-matter experts also contains empty records for many keywords.

Having successfully established the context, the TIRM process sponsor and process manager decide that it is now time to move on to stage B to conduct the actual information risk assessment.

Summary

This chapter presented how to establish the context for TIRM. It explained how to set the motivation, goals, initial scope, responsibilities, and context of the TIRM process, and how to establish the external environment. Then, you learned how to analyze the organization and how to identify business objectives, measurement units, and risk criteria as part of the TIRM process. Finally, it discussed how to establish an understanding of the information environment of your organization. The outputs of stage A will be used to facilitate information risk assessment in stage B and information risk treatment in stage C. The next chapter will present the core of the TIRM process, which is the identification, analysis, and evaluation of information risks.

References

1. Buchanan S, Gibb F. The Information Audit: An Integrated Strategic Approach. International Journal of Information Management. 1998;18(1):29–47.

2. Earl MJ, Khan B. How New Is Business Process Redesign? European Management Journal. 1994;12(1):21.

3. Grundy T. Implementing Strategic Change: A Practical Guide for Business. London: Kogan Page; 1993.

4. Harrison R. TOGAF Version 8.1. Zaltbommel, Netherlands: Van Haren Publishing; 2007.

5. Information Architecture Institute. What is Information Architecture? Available at 2013; http://www.iainstitute.org/documents/learn/What_is_IA.pdf; 2013.

6. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 31000:2009 Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines on Implementation. 2009; Available at http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail?csnumber=43170; 2009.

7. Lewin K. Frontiers in Group Dynamics: Concepts, Method, and Reality in Social Science; Social Equilibria and Social Change. Human Relations. 1947;1(1):5–641.

8. Rose-Ackerman S. Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences and Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

9. Stevens SS. On the Theory of Scales of Measurement. Science. 1946;103:667–6680.

10. Trumbull G. Consumer Capitalism: Politics, Product Markets, and Firm Strategy in France and Germany. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2006.

11. Wang RY, Strong DM. Beyond Accuracy: What Data Quality Means to Data Consumers. Journal of Management Information Systems. 1996;12(4):33.

12. Weill P. Innovating with Information Systems: What Do the Most Agile Firms in the World Do? Presentation at the Sixth e-Business Conference. Barcelona: Spain; 2007.

13. Zachman JA. A Framework for Information Systems Architecture. IBM Systems Journal. 1987;26(3):276–292.