Information Security Management Handbook, Sixth Edition (2012)

DOMAIN 3: INFORMATION SECURITY AND RISK MANAGEMENT

Security Management Concepts and Principles

Chapter 3. Appreciating Organizational Behavior and Institutions to Solidify Your Information Security Program

Robert K. Pittman, Jr.

Introduction

Throughout life, many of us commute to and from our occupation, travel during vacation to other states and perhaps other countries, spend quality time with our family, as well as find time for entertainment at a sporting event, a play, the beach, or a concert. Many of these trips and activities place us in an environment where people exist. People are unavoidable, regardless of where we commute or where our travels take us. In the gathering of people, there exists a culture that requires a keen knowledge and insight to ascertain how you should approach an individual(s). To identify an appropriate approach is warranted but challenging when establishing or cultivating an information security program, regardless of the sector (e.g., public, private, and nonprofit) in which you are employed.

Many well-known theorists like Douglas McGregor (created the Theory X and Y model), Edgar Schein (created the Organization Culture model), as well as psychologist Abraham Maslow, who created the Hierarchy of Needs five-level model, and numerous others in the field of organizational behavior and culture research have brought this topic to the forefront because of their immense research and the value that it brings to organizations worldwide.

Organizations throughout the world use government businesses essentially supported by the public. The public comprises its citizens and constituents, its businesses such as nonprofit organizations and corporations, including government agencies at all levels. A relationship among everyone involves citizens in terms of governments and associated organizations interrelating their programs and services on behalf of the public. At least, this is one of the goals of governments, because they are providing services that a corporate business would not even consider. The plethora of services being provided to the public are social services, general government, healthcare, and public safety.

Some of the countless government social services programs include addressing and supporting low-income families, foster care, emancipated youths, and general relief payments for food and housing for the disadvantaged. Other services, including property value assessment, property tax payment, requests for a birth certificate, a marriage license, or a death certificate, as well as simply registering to vote, in part, constitute general government services. Our citizens, from the time they are brought into this world and throughout their lives will require healthcare services. Medical and mental healthcare, including public health issues, will always be of prime concern to all levels of government, involving all ages. It may seem obvious that public safety services are at the top of the list with healthcare as well. The security of our homeland, the protection of our borders and ports, law enforcement, and protection of our loved ones is an area where government visibly plays a significant role.

All of the aforementioned government services are provided externally to the citizens. The perspective on services provided internally would be contrary to corporate services, in terms of the existence and loyalty of a significant number of employee’s labor unions (i.e., Civil Service Rules), attractive sustained retirement packages, consistent health and dental benefits, career and job advancements within the same government level where opportunities exist in different departments, branches, and agencies, and are knowingly supporting a cause or the application of Greek philosophy using Aristotle’s definition of greater good.

Regardless of the lens that we use to view government and corporate (i.e., comprised of both the market activities of the individuals and the actions of organizations as corporate actors) (Coleman 1990) obvious differences do exist. Much of government services are provided to the public are unique as compared to corporate provided services. These unique government services (e.g., Social Work, Probation Officer, Librarian) are predominately performed by government employees that are usually passionate about their work including a strong will to deliver good service. Later in this chapter, you will become acquainted with the lack of similarities from the perspective of institutions.

By viewing a government at the 80,000-foot level and viewing through a Looking Glass, differences exist between the perspective of an employee and an organization. Differences exist between local government (i.e., county and city) organizations and corporations (e.g., corporate stock shares and well-compensated). Therefore, the establishment of an information security program differs significantly between local governments and corporations.

To establish an information security program in local government involves an array of focal points that must be addressed within the initial 18 months by the chief information security officer (CISO), chief security officer (CSO), or information security manager (ISM). Additionally, in some recent information security forums and industry writings, the chief risk officer (CRO) may have a significant role. It is imperative that these focal points are addressed in terms of having them established and adopted by the organization:

![]() Enterprise information security policies

Enterprise information security policies

![]() Information Security Steering Committee (ISSC)

Information Security Steering Committee (ISSC)

![]() Enterprise information security program

Enterprise information security program

![]() Enterprise information security strategy

Enterprise information security strategy

![]() The organization’s health level based on an information security risk assessment

The organization’s health level based on an information security risk assessment

![]() Enterprise and departmental (or agencies) Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs)

Enterprise and departmental (or agencies) Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs)

![]() Enterprise Security Engineering Teams (SETs)

Enterprise Security Engineering Teams (SETs)

These focal points can be categorized as your “Lucky 7,” and will be referred to as such throughout this chapter. The security professional who addresses these points will be “lucky,” and the others will not be as “lucky” in terms of continued employment with that particular organization, because the primary responsibility exists with the information security unit. This may sound harsh; however, at the end of the day the business and services being provided to the citizens and constituents expect their confidential, sensitive, and personally identifiable information (PII) is secured and protected. It is the job of the information security professional to accept the challenge and responsibility to ensure that the organization stays away from any press or media release announcing a data breach, or perhaps, a breach of trust. As information security practitioners are aware, there has been a plethora of announcements in the press and media regarding organizations (public and private sectors) that have experienced computer security breaches. These breaches occurred in corporate America, colleges and universities, healthcare organizations, as well as the 26 million veterans’ records with PII that are the responsibility of the federal government Veteran’s Administration (public sector) and T.J. Maxx’s 45.7 million credit and debit card owners (private sector) that occurred in 2005. However, the all-time record breach occurred in 2009 with Heartland Payment Systems, which now leads all of the hacks that have hit or affected the financial services industry (private sector), with 130 million credit and debit card account numbers compromised.

Organizational Governance

It seems increasingly apparent that the public sector leverages a security-related event to promote an information security program, or at the minimum, obtain a funding source to support a project or initiative. Despite the consequences of failure or compromise, security governance is still a muddle. It is poorly understood and ill defined, and means different things to different people. Essentially, security governance is a subset of enterprise or corporate governance. Moreover, one could identify governance as: security responsibilities and practices; strategies and objectives for security; risk assessment and management; resource management for security; and compliance with legislation, regulations, security policies, and rules.

Information security governance is “the establishment and maintenance of the control environment to manage the risks relating to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information and its supporting processes and systems.”

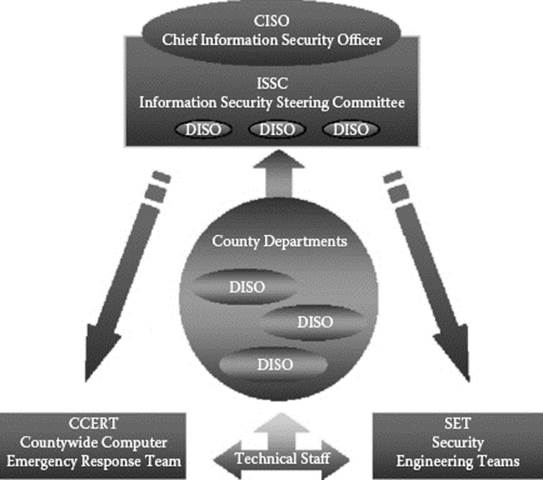

From a local government perspective, the county government is governed by a five-member board of supervisors and the chief executive officer (CEO). The CISO, the departmental information security officers (DISOs), and the ISSC or a security council comprise the information security governance.

A federated organizational structure is the norm for the majority of local government organizations. If the discussion is about county or city government, numerous business units or departments serve unique and differing business purposes. Because of these unique business units, comprehensible governance is vital to the success of any information security program. This governance involves a strategic organization framework (Figure 3.2) that provides a clear illustration of the involved players. The “Security Triangle” (Figure 3.1) is a framework that is doable for the CISO’s organization, regardless if their information technology (IT) is decentralized, centralized, or a managed-security service. Additionally, a local government organization can be deemed as an organization with 30 or more corporations, in terms of having 30+ county departments with distinct businesses as they serve their respective constituents.

Table 3.1 The Public Sector versus the Private Sector and Corporate Organizations

|

Public-Sector |

Private-Sector |

Public Corporation |

|

Director |

Owner |

Board of Directors |

|

Deputy Director/Branch Manager |

Vice President |

Executive management |

|

Division Chief |

Manager |

Middle management |

|

Section Manager |

Manager |

Supervisory management |

|

Associate |

Employees |

Employees |

The organization’s senior management must support the Security Triangle; however, articulation of this support should be achieved by the development of Board-adopted policies (Table 3.1). These policies are similar to the corporate world where the Board of Directors and the CEO can adopt policies. However, an information security council or steering committee can approve information standards and procedures. The use of an advisory council or committee provides a weaker connotation that is not supportive of establishing or sustaining an information security program.

Organizational Culture and Behavior

Bruce Schneier is an internationally renowned security technologist and author, as well as the well-respected security expert for business leaders and policy makers. Currently, he is the chief security technology officer for BT Managed Security Solutions. In his book, Beyond Fear, Thinking Sensibly about Security in an Uncertain World, Schneier states that security is all about people: not only the people who attack systems, but also the people who defend those systems. If we are to have any hope of making security work, we need to understand these people and their motivations. We have already discussed attackers; now we have to discuss defenders.

Schneier also states that good security has people in charge. People are resilient. People can improvise. People can be creative. People can develop on-the-spot solutions. People are the strongest point in a security process. When a security system succeeds in the face of a new, coordinated, or devastating attack, it is usually due to the efforts of people. (See the section Organizations Are Institutions, for more detail.)

If it was not obvious prior to reading this chapter, it should be obvious now that people play a significant and critical role as part of any information security program. Moreover, those same people at times can bring about challenges, as well. However, the culmination of people defines organizational behavior and its culture. Organizational culture is the culture that exists in an organization, something akin to a societal culture. It is composed of many intangible phenomena, such as values, beliefs, assumptions, perceptions, behavioral norms, artifacts, and patterns of behavior. The unseen and unobserved force is always behind the organizational activities that can be seen and observed. Organizational culture is a social energy that moves people to act. “Culture is to the organization what personality is to the individual—a hidden, yet unifying theme that provides meaning, direction, and mobilization.”

Organizations are assumed to be rational-utilitarian institutions whose primary purpose is the accomplishment of established goals (i.e., information security strategy and initiatives). People in positions of formal authority set goals. The personal preferences of an organization’s employees are restrained by systems of formal rules (e.g., policies, standards, and procedures), authority, and norms of rational behavior.

These patterns of assumptions continue to exist and influence behaviors in an organization because they have repeatedly led people to make decisions that “worked in the past.” With repeated use, the assumptions slowly drop out of people’s consciousness but continue to influence organizational decisions and behaviors even when the environment changes and different decisions are needed. The assumptions become the underlying, unquestioned, but largely forgotten reasons for “the way we do things here”—even when such ways may no longer be appropriate. They are so basic, so ingrained, and so completely accepted that no one thinks about or remembers them. (See the section Organizations Are Institutions, for more detail.)

In the public sector, it seems that almost every employee has worked at least 20 years or more. In retrospect, they may have worked many years less. Reality sets in when many employees consistently echo the phase, “this is the way we do things here.” As the CISO, attempting to implement one of your many information security initiatives, this echo seems to sound loudly, increasing exponentially with the employees that will be affected by implementing a change to their environment. This type of behavior illustrates the presence of a strong organizational culture.

A strong organizational culture can control organizational behavior. For example, an organizational culture can block an organization from making changes that are needed to adapt to new information technologies. From the organizational culture perspective, systems of formal rules, authority, and norms of rational behavior do not restrain the personal preferences of an organization’s employees. Instead, they are controlled by cultural norms, values, beliefs, and assumptions. To understand or predict how an organization will behave under varying circumstances, one must know and understand the organization’s patterns of basic assumptions—its organizational culture.

Organizational cultures differ for several reasons. Some organizational cultures are more distinctive than others. Some organizations have strong, unified, pervasive cultures, whereas others have weaker or less pervasive cultures; some cultures are quite pervasive, whereas others may have many subcultures existing in different functional or geographical areas.

By contrast, using “prescriptive aphorisms” or “specific considerations in changing organizational cultures” when this occurs, your information security program (i.e., Lucky 7) along with its processes and practices will flourish with positive outcomes:

![]() Capitalize on propitious moments.

Capitalize on propitious moments.

![]() Combine caution with optimism.

Combine caution with optimism.

![]() Understand resistance to culture change.

Understand resistance to culture change.

![]() Change many elements, but maintain some continuity and synergy.

Change many elements, but maintain some continuity and synergy.

![]() Recognize the importance of a planned implementation.

Recognize the importance of a planned implementation.

![]() Select, modify, and create appropriate cultural forms.

Select, modify, and create appropriate cultural forms.

![]() Modify socialization tactics.

Modify socialization tactics.

![]() Locate and cultivate innovative leadership.

Locate and cultivate innovative leadership.

Altering the organizational culture is merely the first—but essential—step in reshaping organizations to become more flexible, responsive, and customer-driven. Changing an organizational culture is not a task to be undertaken lightly, but can be achieved over time.

Organizational cultures are just one of the major tenets that constrain the establishment and building of an information security program. As a CISO, or an information security practitioner within your organization, you should have at least some interaction with the various target groups (i.e., stakeholders) to grasp an awareness of their behavior. Table 3.2 illustrates the expected behavior of the target groups and the desired behavior to assist in driving your program. This chart will prove beneficial when you are assessing each stakeholder from your perspective.

Table 3.2 Stakeholders’ Desired Behavior

|

Organizational Target Group |

Desired Behavior |

|

Board of Supervisors/City Council |

Endorsement |

|

Executive management |

Priority |

|

Middle management |

Resources |

|

Supervisory management |

Support |

|

Employees |

Diligence |

|

Constituents/Consumers |

Trust |

|

Security Program |

Execution |

Organizations Are Institutions

When discussing organizational culture, it is moot if we are referring to government or corporation. To extend the conversation on culture, a CISO must have a clear understanding of institutions. The term “institution” designates organizations of every kind. To avoid confusion, it is useful to distinguish between institutions and organizations. Institutions are the rules of the game; organizations are corporate actors, i.e., groups of individuals bound by some rules designed to achieve a common objective (Coleman, 1990). They can be political organizations such as political parties, educational organizations such as universities, social services organizations such as a government department, or economic organizations such as firms. Therefore, organizations, when interacting with other organizations or individuals, submit to those general social rules called institutions, i.e., they are equally constrained by the general rules of the game. Essentially, institutions are simply normative social rules, or rules of the game in a society, enforced through the coercive power of the state or other enforcement agencies that shape human interaction (Mantzavinos, 2001). This interaction is vital to establishing and sustaining your information security program. Institutions exist based on an individualistic approach. The first class of reasons refer to the human motivational possibilities and the second class to cognitive possibilities. The main assumption about motivation is that every individual strives to increase his/her utility or, in other words, that every individual strives to better his/her condition by all means available to him/her. Obviously, conflicts between individuals are bound to arise. From the perspective of the observer, however, such social problems are clearly identifiable, and their basic characteristic is that the utility obtained by some kind of individual behavior depends in one way or another on the behavior of other individuals. Some stylized social problems have been identified in game theory or the game of trust. When asking the question of why not solve social problems ad hoc because, in a way, every problem situation—and thus every social problem—is unique, the response is associated with the cognitive structure of the human mind. The human mind is far from being a perfect tool, able to perform all the difficult computations needed for solving problems that arise from interacting with other minds. Because of a restricted cognitive capacity, every individual mobilizes his/her energies only when a “new problem” arises, and follows routines when the individual classifies the problem situation as a familiar one. This distinction is rooted in the limited computational capacity of human beings and is a means to free up an individual’s mind from unnecessary operations so that the individual can deal more adequately with the problem situations arising in the individual’s environment (Mantzavinos, 2001).

The individual’s environment could be deemed complex. This precisely indicates that the individual’s limited cognitive capacity makes their environment appear rather complicated for the individual and in need of simplification to be mastered. This refers to both the natural and the social environment of the individual. Because of the perceived complexity of the social environment, people consciously or unconsciously adopt rules as solutions to social problems rather than deciding each time anew how to act and react to the settings where coordination with other individuals is needed. Rules in general, “are a device for coping with our constitutional ignorance”; they are the “device we have learned to use because our reason is insufficient to master the full detail of complex reality (Hayek, 1960).”

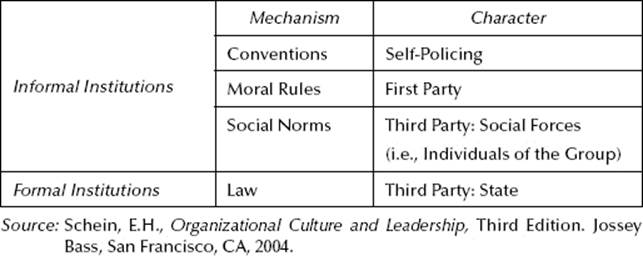

A very productive and very widely used distinction among types of institutions is based on the criterion of the enforcement agency of institutions. Institutions are commonly classified according to the criterion shown in Table 3.3.

The most important feature of conventions is their self-policing character. After they have emerged, nobody has an incentive to change the rules that everybody else sticks to. In game theory, conventions are usually analyzed with the help of what are known as “coordination games.” Examples of such rules are traffic rules (e.g., traffic speed signs are regulatory), industrial standards, forms of economic contracts, language, etc. The moral rules are largely culture-independent because they provide solutions to problems that are prevalent in every society, as Lawrence Kohlberg has shown in his famous empirical research (Kohlberg, 1984). These rules (e.g., policy and standards) are critical to establishing and sustaining an information security program, as well as assisting in culture change. The mechanisms for the enforcement of moral rules are entirely internal to the individual, and therefore no external enforcement agency for rule compliance is required. Typical examples of moral rules are “keep promises,” “respect other people’s property,” “tell the truth,” etc. These have a universal character. However, their existence does not necessarily mean that they are followed, and in fact, many individuals break them. (Thus, the empirical phenomenon to be explained is the existence of moral rules in a society, which are followed by part of the population.) On the contrary, social norms are not of universal character, and they are enforced by an enforcement agency external to the agent, usually the other group members. The mechanism of enforcement refers to the approval or disapproval of specific kinds of behavior. Social norms provide solutions to problems of less importance than moral rules and regulate settings appearing mainly at specific times and places.

Table 3.3 Informal and Formal Institutions

The enforcement agency (i.e., conventions, moral rules, and social norms) of each different category of informal institution (Table 3.3) is different, as is the specific enforcement mechanism (i.e., approval or disapproval of specific kinds of behavior). The common element between each type of informal institution, and this is critical, is when all emerge as the unintended (i.e., not planned) outcome of human action (Mantzavinos, 2001). It may be obvious that this outcome may be favorable or unfavorable depending on the situation as it relates to the previously described equation.

Their mechanism of emergence is thus an evolutionary process of the invisible-hand type. This process starts when an individual perceives his/her situation as constituting a new problem because the environment has changed, and then in an act of creative choice, the individual tries a new solution to this problem. Both the problem and its solution are of a strictly personal nature, and the solution is attempted because the individual expects it to increase their utility.

Whereas informal institutions emerge from the unintended results of human action in a process that no individual mind can consciously control, a law or the sum of the social rules that are called formal institutions, are products of collective decisions. The state as an organism* creates law by constructing the conscious decision of its organ’s new legal rules or by providing a means of suitable adaptation—existing informal rules with sanctions (Gemtos, 2001: 36).

Informal institutions are generated through an invisible-hand process in a way from within the society. The formal institutions are the outcome of the political process, which are imposed exogenously onto the society from the collective decisions of individuals who avail of political, economic, and ideological resources. On the other hand, this is reflective of an institution adopting policies and standards to address a baseline for their information security practices for compliance by its employees. There is no necessity for informal and formal institutions to complement each other in such a way that a workable social order is produced or even more, in order for the economic development of a society to take place.

Information Security Executive in the Organization

The late, legendary, men’s head basketball coach at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), John Wooden, wrote “there is a choice you have to make in everything you do, so keep in mind that in the end, the choice you make makes you.” Nowhere is this more evident than the relationships that are established throughout your organization, as well as external to the organization. Surround yourself with people who add value to you and encourage you. At the minimum, having photographs or prints hanging on your office walls of individuals who have achieved greatness, regardless of the industry, will provide an added psychological benefit when tough decisions must be made. If the opportunity presents itself, where you are able to visit my business office or home office, this psychological benefit is apparent. In plain sight, you will see the memories of and fondness for greatness from the first African-American athlete to enter major league baseball, Jackie Robinson; Muhammad Ali (born Cassius Clay), who changed the culture of boxing to a style, business, and character (e.g., charisma) that was not seen previously; and Louis Armstrong (nicknamed Satchmo), who was once proclaimed the greatest musician to ever live and the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of Time magazine on 21 February 1949. Without doubt, these individuals changed their respective institution’s culture overnight. The establishment of strong relationships is an excellent indicator of a strong CISO; however, staying visible in the organization is equally important and provides a path to having a positive information security culture throughout your organization (e.g., department, agency, and division).

People can trace the successes and failures in their lives to their most significant relationships. Establishing relationships is part of our livelihood in terms of family, personally, professionally, and business. Moreover, as the CISO, when establishing an information security program and chairing an ISSC meeting with your security peers or colleagues in your organization, those relationships are imperative to your success. Effective CISOs have learned how to gain the trust and confidence of the executive team. The CISO must remember that security is easier to sell if the focus is on the benefits to the company. Sometimes, while selling security, analogs associated with personal and home practices will provide clarity and additional reinforcement.

The CISO is the information security executive (i.e., senior management), regardless of whether we are referencing public, private (i.e., Corporate American), or nonprofit sector organizations. Regardless of the sector, an organization’s CISO must address the big picture and must rely on timely and actionable risk information that enhances his/her ability to make decisions that will drive local government efficiencies and operational effectiveness.

In local government, many CISOs are using a matrix reporting structure and either report to the chief information officer (CIO) or the CEO, and ultimately the city manager, board of supervisors (board), or city council (council). Actually, this matrix model can only function in this fashion as long as no operations responsibilities are incorporated. In other words, the daily operational activities and tasks may collide, at the minimum, with the strategic and tactical mindset of the information security practitioner. This model has brought this author numerous successful implementations of information security projects and initiatives, including program sustainability.

However, there are many other ways to organize the security function and they all have advantages and disadvantages. Strong CISOs understand that it is not important how security or the hierarchical structure is organized. The key to success is the support structure that the CISO is able to build among the executive team. However, the manner in which security is organized will change the methods and processes that a CISO will use to be successful. Effective CISOs will adapt their approach to the most advantageous organizational structure. The two primary and most common organization structures are (1) the matrix structure, in which the CISO is an enterprise-level (or corporate-level for private sector) organization and the security staff report in the business lines; or (2) the CISO has direct or indirect (e.g., dotted-line organizational structure model) responsibility for the implementation and operations of security.

Smart CISOs understand that they do not need to have all the security staff in their direct reporting line. Be ready for decentralization. Being a strong CISO is not about how many staff you manage; it is about how many staff you can influence. Drive the difference of security any way you can—through direct staff, matrix staff, and supporting staff—to reach the security program goals and initiatives. Large organizations have already implemented a matrix organization or are seriously reviewing how to manage their business lines more effectively. Be prepared to manage in a matrix organization.

Regardless of the reporting structure, decisions are made to eliminate press clippings in tomorrow’s local newspaper or perhaps the national news. The CISO cannot be risk-adverse. All information security practitioners should think quantitatively. This does not necessarily mean doing calculations. Rather, it means thinking about things in terms of the balance of arguments, the force of each of which depends on some magnitude.

Some local government organizations are forward-thinking companies that have recognized that business and IT executives (e.g., CIO, CISO, or chief technology officer) need to establish standardized, repeatable ways to identify, prioritize, measure, and reduce business and technology risks, both collaboratively and effectively. Moreover, security executives who were accustomed to working in their own silo must now consider all business-related risk areas to align initiatives (e.g., business and applications system migration projects and customer-based applications to enhance e-government/e-services) properly with exposures.

Collaboration and communication are sunshine on its brightest day. Team relationships and/or team meetings are training gold nuggets. If the opportunity exists, inviting individuals to attend selected meetings within your security program can go a long way to helping them understand the scope and breadth of security. Make them an honorary member of the team. This has been done on several occasions to break through the myopia barrier. In addition, if other groups allow you to attend a team meeting or two, go for it. This seems very simple, and it is, but it can be unbelievably powerful.

Table 3.4 The Stages of Group/Team Evolution

|

Stage |

Dominant Assumption |

Socioemotional Focus |

|

Group/Team Formation |

Dependence: “The leader knows what we should do.” |

Self-Orientation: Emotional focus on issues of: 1. Inclusion, 2. Power and influence, 3. Acceptance and intimacy, and 4. Identity and role. |

|

Group/Team Building |

Fusion: “We are a great group/team; we all like each other.” |

Group/Team as Idealized Object: Emotional focus on harmony, conformity, and search for intimacy. Member differences are not valued. |

|

Group/Team Work |

Work: “We can perform effectively because we know and accept each other.” |

Group/Team Mission and Tasks: The emotional focus is primarily on accomplishment, teamwork, and maintaining the group in good working order. Member differences are valued. |

|

Group/Team Maturity |

Maturity: “We know who we are, what we want, and how to get it. We have been successful, so we must be right.” |

Group/Team Survival and Comfort: The emotional focus is preserving the group/team and its culture. Creativity and member differences are seen as threats. |

Source: Mantzavinos, C., Individuals, Institutions, and Markets, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001.

It is very true that there is success in numbers from an empirical perspective, where teams can drive your information security program. Two types of teams should be implemented to support an information security program: proactive and reactive.

The proactive measures teams we call the SETs. These teams develop and review policies, standards, procedures, and guidelines and are usually experienced and knowledgeable in terms of the technical, culture, and organizational perspectives. These teams address host strengthening and isolation, policy and operating procedures, malware defense, and application security, to name a few. However, there will be opportunities where a proactive team will be formed to address a point-in-time project. For example, our implementation of an Internet content filter was a win-win because of the formulation of a SET from the development of the technical specifications to enterprise deployment. Once deployed throughout the organization, the team was no longer required.

A reactive team addresses an enterprisewide CERT. This team reacts to situations that potentially affect or have affected the enterprise network, servers, applications, workstations, etc. This team is reactive in nature. However, use of a structured methodology while responding, resolving, and reporting the incident is vital. Use of well-maintained and clearly written documentation (e.g., narratives, matrixes, and diagrams) for responding to incidents and use of a standardized incident reporting form are crucial. It may be obvious that by defining the various types of information security incidents to report will provide one of the numerous performance metrics that can be established to measure a portion of the operational aspects of your program (Table 3.4).

Information Security Policies, Standards, Procedures, and Guidelines

One of the major and critical components of an information security program is the formulation, collaboration, and adoption of information security policies. These written policies cannot survive without associated supporting standards, procedures (some private sector organizations use standard operating procedures [SOPs]), and guidelines. Personally, having clear, distinct, and physically separated policies, standards, and procedures would provide benefits to your overall information security program.

Charles Cresson Wood, well known in the information security industry as a leader for information security policy development, has emphasized segregating information that has different purposes. Specifically, one should formulate different documents for policy, standards, procedures, and guidelines. This structure provides numerous benefits to the responsible owner of these documents in terms of ease of modification to maintain currency and relevance, reviews and approvals are more efficient, and requests for any single type of document can be distributed on a need-to-know basis that protects the security and privacy of the written information, where applicable.

Policy is defined as the rules and regulations set by the organization (including addressing institutional issues). Policies are laid down by management in compliance with applicable laws, industry regulations, and the decisions of enterprise leaders and stakeholders. Policies, standards, and procedures are mandatory; guidelines are optional. However, policies can be used to clearly define the roles and responsibilities of the information security program, including the CISOs, the steering committee, etc. Moreover, policies are written in a definite, clear, and concise language that requires compliance. The failure to conform to policy can result in disciplinary action, termination of employment, and even legal action.

Information security policy governs how an organization’s information is to be protected against breaches of security. Familiar examples of policy include requirements for establishing an information security program, ensuring that all laptops are deployed with automatic hard disk encryption software, employees’ Internet usage, security awareness and training, malware (e.g., antivirus, antispam, and antispyware) defense, and computer incident reporting for employees, to name a few.

Information security standards can be an accepted specification for software, hardware, or human actions. These standards can also be de facto when they are so widely used that new applications routinely respect their conventions. However, the written format is preferred and recommended from the perspective of an information security professional and IT professionals including auditors.

A software standard can address a specific vendor’s solution for antivirus software protection. In fact, from a defense-in-depth perspective, an organization may standardize on two vendor’s solutions. If a particular organization has implemented all Cisco Systems Inc. (Cisco) network devices, they could conclude that their hardware standard for network infrastructure is Cisco. There are many standards to address human actions and even their behavior. For example, to address a potential computer security breach, a standard will address actions to be performed by specific employees’ roles, responsibilities, and timelines for an appropriate response.

Procedures prescribe how people are to behave when implementing policies. For example, a policy might stipulate that all confidential and private data network communications from employees who are working or traveling and want to connect externally to the enterprise network must be encrypted. This would constitute previously identified software and hardware (perhaps an adopted standard for communicating externally) required to be implemented based on policy. The corresponding procedure (the “how-to”) would explain in detail each step required to initiate a secure connection using a particular virtual private network (VPN) or some other technology.

As previously stated, policies, standards, and procedures are mandatory. However, guidelines are not mandatory. Guidelines could be used as a documented standard or procedure that, invariably, in the future could be transformed and adopted into a standard or procedure. Guidelines can be established to assist with specific security controls that may be transformed into a standard or perhaps a procedure. For example, if an organization prefers using the Windows Mobile operating system for all mobile devices; however, there is a small community within the organization that prefers the proprietary Blackberry device. Therefore, one may have to satisfy both communities. A guideline would be feasible to address the appropriate security controls for the Blackberry device, where a standard would address the appropriate security controls for all Windows Mobile devices. Eventually, the Blackberry security controls guideline would be transformed into a standard after a greater acceptance within the organization was achieved. This eliminates the use of a de facto standard in this example.

All documents should use suitable policy resources, including the aforementioned Charles Cresson Wood’s Information Security Policy Made Easy, government (e.g., National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST], National Security Agency [NSA] Security Guidelines, and RFC 2196), industry bodies (e.g., International Standards Organization [ISO] 17799/27002, Control Objectives for Information and related Technology [COBIT], and Committee of Sponsoring Organizations [COSO]), and commercial (e.g., Microsoft) organizations in preparing to formulate policies and standards.

The writing style should state what employees can do and what they cannot do, and use short sentences, written at a tenth-grade level similar to the model that newspapers use; review and improve (i.e., the sunset date), or adapt policies regularly; circulate drafts showing changes in policies to the stakeholders and the interested participants prior to adoption, and articulate major changes to senior management (e.g., department heads, counsel, CIOs, and privacy officers) within the enterprise.

Information Security Organization

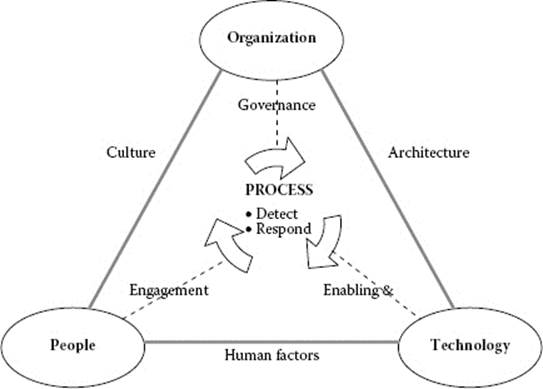

The organizational culture and behavior, the CISO as the information security executive, and the organization structure are the dependent variables in establishing an information security program. The framework that has been proved by numerous local governments west of the Mississippi River, regardless of the workforce size, is the “Security Triangle” (Figure 3.1). This framework has paid dividends in having clearly defined roles and responsibilities, while addressing defense and offense strategies. In other words, these strategies are the previously stated reactive and proactive teams that allow for continual collaboration with stakeholders vertically and horizontally throughout the public sector organization.

Figure 3.1 Information security strategic organization security triangle.

The following information security strategic organization diagram (i.e., the Security Triangle) depicts an example from a local government (i.e., county government). It illustrates the CISO at the top of the organization who may report to a CIO or CEO, as previously stated. The ISSC is composed of the DISOs. This will provide a forum for all information security-related collaboration and decision making. This deliberative body will weigh the balance between heightened security and departments performing their individual business. The ISSC responsibilities will be to

![]() Develop, review, and recommend information security policies

Develop, review, and recommend information security policies

![]() Develop, review, and approve best practices, standards, guidelines, and procedures

Develop, review, and approve best practices, standards, guidelines, and procedures

![]() Coordinate interdepartmental communication and collaboration

Coordinate interdepartmental communication and collaboration

![]() Coordinate countywide education and awareness

Coordinate countywide education and awareness

![]() Coordinate countywide purchasing and licensing

Coordinate countywide purchasing and licensing

![]() Adopt information security standards.

Adopt information security standards.

The DISOs are responsible for departmental security initiatives and efforts to comply with countywide information security policies and activities. They also represent their departments on the ISSC. To perform these duties, the DISO must be established at a level that provides management visibility, management support, and objective independence. The DISO responsibilities include:

![]() Representing their department on the ISSC

Representing their department on the ISSC

![]() Developing departmental information security systems

Developing departmental information security systems

![]() Developing departmental information security policies, procedures, and standards

Developing departmental information security policies, procedures, and standards

![]() Advising the department head on security-related issues

Advising the department head on security-related issues

![]() Developing department security awareness programs

Developing department security awareness programs

![]() Conducting information security and privacy self-assessments/audits

Conducting information security and privacy self-assessments/audits

The Countywide Computer Emergency Response Team (CCERT) will respond to information security events that affect several departments within the county with actions that must be coordinated and planned. The CCERT is comprised of membership from the various departments that are often members of the Departmental Computer Emergency Response Team (DCERT). The CCERT team meets biweekly to review the latest threats and vulnerabilities and ensures that membership data is kept current. The CISO participates in their activities, as well as leads the response to cyber-related events. Efforts include improved notification and communication processes, and ensuring that weekend and after-hours response is viable. Additionally, training will be conducted to provide forensic capabilities to the CCERT team members, but specific to the incident response in terms of maintaining the chain-of-custody of electronic evidence.

The Information Security Strategic Framework (Figure 3.2) developed to support local government is designed to address the organization, people, processes, and technology as they relate to information security. The strategy is based on the principle that security is not a onetime event, but must be a continuously improving process, an emergent process that addresses changes in business requirements, technology changes, new threats and vulnerabilities, and a need to maintain currency with regard to software release levels at all levels within the security network, server, and client arena. It is also based on the realization that perfect security is an impossible goal and that efforts to secure systems must be based on the cost of the protective measures versus the risk of loss.

As the CISO or ISM, many of these protective measures are identified in an information security strategy, as a necessity. A documented strategy that is annually reviewed is imperative to ensure the currency of the projects and initiatives for that particular fiscal year. It is prudent that, as the information security practitioner, you align your security projects, initiatives, and activities with the annual budget process of the organization. This will provide a means and awareness to senior management that funding is mandatory to sustain a true information security program that will reduce risk. This strategy must clearly articulate the mission and vision of the program. Additionally, information security program goals and objectives are articulated in the strategy, in terms of short- and near-term timelines. For example, your high-level goals can be derived from the 12 information security domains that are articulated in the ISO 27002 standard. The objectives will support the stated goal that should apply to your organization’s required level of security protections. The strategy will assist in the CISO’s ability to achieve the stated goals and objectives over a defined period.

Figure 3.2 Information security strategic framework.

Conclusion

Today’s information security professional practitioner is increasingly being challenged in numerous facets that are warranted based on the numerous human and technological (e.g., mobile device or Bring Your Own Device, virtualization, and cloud computing) threats and vulnerabilities that exist in the world. Globally, government organizations and major software houses experience constant probing for various reasons. While discussing local government or private sector organization challenges, some specific areas are unique to government, such as the diversity of businesses and services under a single organization (i.e., county or city government), the type of businesses that warrant differing security and privacy protections, multiple legislations and regulations that sanction departments within a local government organization, and perhaps most of all the organizational and institutional culture issue because of the Civil Service Rules that provide difficulty when employee termination is considered.

The CISO responsibilities range through establishing and sustaining relationships with executive management, learning about the organization’s culture and behavior including the institutional culture, constantly being visible and communicating the security message throughout the organization, having formulated clearly defined policies, standards, and procedures, and establishing a governance structure that comprises and establishes a successful information security program.

In today’s global society, a career path definitely exists for information security practitioners that would ultimately lead to holding a position as a CISO or CSO. This chapter as well as other chapters in this book should provide dividends throughout your career as a practitioner. However, having a business acumen, IT experience, management, soft skills, enormous leadership, and organizational skills are only a few of the major tenets in striving to be an outstanding and successful CISO. On the other hand, the IT training curriculum does not usually include managerial skills, such as leadership, team building, collaboration, risk assessment, and communication skills including negotiations, as well as psychology and philosophy courses.

About the Author

Robert K Pittman, Jr., MPA, is a public sector employee with over thirty-two years in the field of information technology and seventeen years within the field of information security. He is a third-year doctoral degree candidate with interest in the field of organizational behavior and culture at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, California.

References

Coleman, J. Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1990.

Gemtos, P. A. Institutions. The sage handbook of the philosophy of social services. Retrieved from: http://www.mantzavinos.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Mantzavinos-chapter-19.pdf. 2010, p. 405.

Hayek, F. A. The Constitution of Liberty. Routledge, London and New York, 1960.

Kohlberg, L. Essays on Moral Development. Vol. II, The Psychology of Moral Development. The Nature and Validity of Moral Stages. Harper & Row, New York, 1984.

Mantzavinos, C. Individuals, Institutions, and Markets, Chapter 6. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001.

* See the famous definition of the modern state of Max Weber (1919/1994: 36): “The state is that human Gemeinschaft, which within a certain territory (this: the territory, belongs to the distinctive feature) successfully lays claim to the monopoly of legitimate physical force for itself.”