Supplier Relationship Management: How to Maximize Vendor Value and Opportunity (2014)

Chapter 4. Introducing Supplier Interaction Models

The Framework for SRM Success

One of the core ambitions we had when we developed the TrueSRM program was to develop a practical framework that actually worked. Too many prior SRM initiatives got stuck at a philosophical level that let companies believe things like the idea that they should partner with all suppliers.Chapter 2 discussed other SRM initiatives that have focused fully on processes and IT systems that manage who is talking to which supplier about what. While this aspect of the system might be useful, it falls short of the true potential in SRM.

The workable framework we aspired to develop aims at a lot more than merely suggesting partnerships or managing processes. As we suggested, in our view, SRM is ultimately about motivating suppliers to behave in ways that will meet a company’s needs.

With this objective in mind, two requirements for the framework emerged:

· It needs to separate those suppliers that really matter from the overwhelming number of suppliers a company usually has.

· It needs to provide specific recommendations on how to interact with suppliers that fall into its different areas.

In order to separate the suppliers that really matter from the others, we looked into dimensions that allow us to gauge what a supplier means to a company. This process was fairly straightforward. We essentially said that it is important to take into consideration the supplier’s current performance and the supplier’s strategic potential. With this, we had the two axes of the SRM framework.

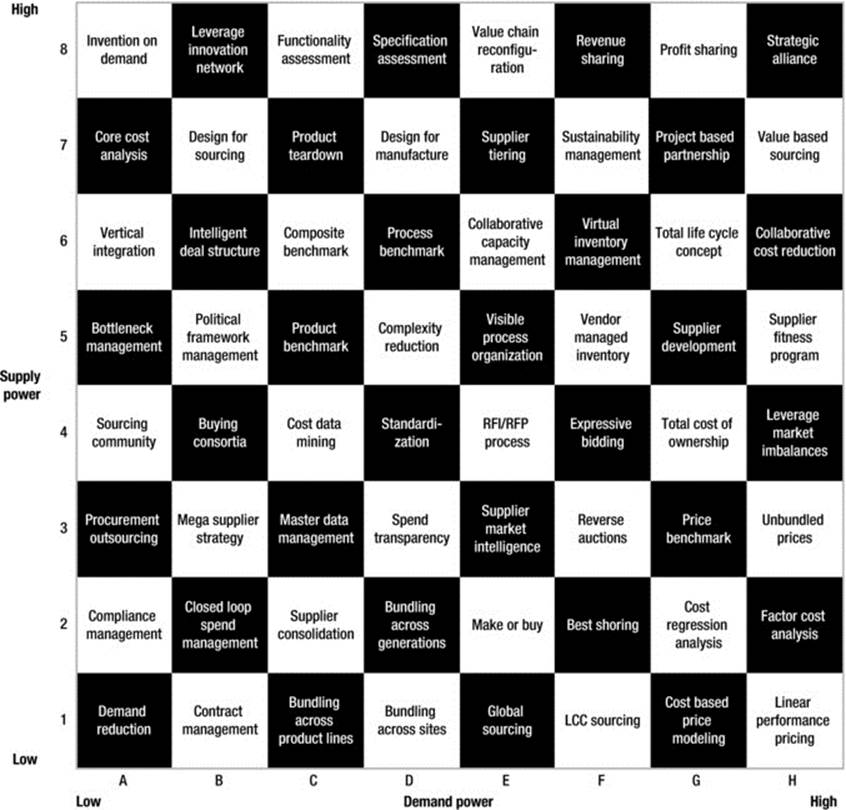

Bringing the framework to life was more challenging. The first question to clarify was whether we would propose distinct models or an unlimited number of shades of grey. Our 2008 book, The Purchasing Chessboard, suggested shades of grey. In this model, a category gets mapped onto the chessboard and then the 64 methods that are in the general area of the category get evaluated for their relevance to the specific category. Since the chessboard (Figure 4-1) is mainly used by specialists dealing with that specific category, this ambiguity made a lot of sense. For further information on the Purchasing Chessboard, see http://www.purchasingchessboard.com .

Figure 4-1. The Purchasing Chessboard

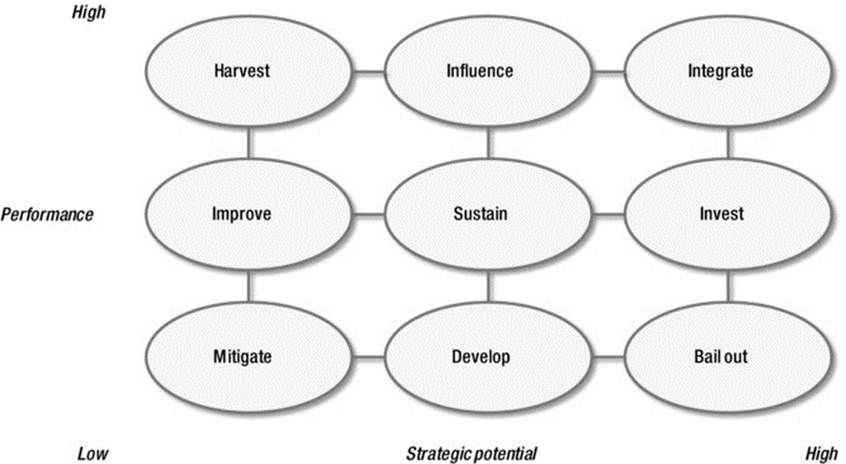

With SRM, we are dealing with a very different environment. The SRM framework will be applied by senior executives from different functional areas. It therefore needs distinct models that are easy to use. After several iterations, we settled on a three-by-three logic with nine distinct supplier interaction models. While it is not trivial to remember nine different models and their position relative to each other, we found it just at the limit of being doable. After a couple of days of practice, senior executives in the pilot companies we worked with got comfortable with the nine interaction models and started using them in a natural way.

This chapter provides a high-level introduction to the two axes of the framework and the nine interaction models (see Figure 4-2).

Figure 4-2. The TrueSRM framework

Performance Axis

There are a number of supplier-performance variables that potentially matter to a customer. At the highest aggregation level, these include time (e.g., on-time, in-full deliveries); cost (e.g., savings vs. the previous period); and quality (e.g., number of implemented improvement ideas in the period).

On a closer look, most systems used to measure the performance of suppliers are not really ideal. Often, the systems are very complex, measuring hundreds of performance indicators, and nobody can explain exactly why their specific indicators and not others are in place. Also, we have observed output factors, like savings performance, and input factors, like the excellence of engineering processes being merged together. Further, weighing factors doesn’t increase the effectiveness of these performance measurement systems.

Then there is the human factor. Different evaluators tend to interpret performance indicators differently and also look at suppliers differently. We have seen wildly fluctuating supplier performance that turned out to be driven not by the supplier’s actual performance but by the variance in people conducting the performance appraisal.

While existing supplier performance measurement systems need to be taken with a grain of salt, they at least provide a starting point for populating the performance axis of the SRM framework. In an ideal world, an SRM initiative might start with overhauling supplier performance management. Each of the functions having interfaces with a supplier would come up with a very limited set of performance indicators. These would then be consolidated into a lean and effective performance indicator structure that would be shared with suppliers.

It is tempting to go down this avenue, but we would not recommend it. Many SRM initiatives have gone wrong doing exactly that. Supplier performance indicators can become very emotional topics that can easily be debated hotly over many months. So, our recommendation is to work with whatever you have today and leave fixing supplier performance measurement for a later point in time.

The real challenge is to make the existing performance measurement meaningful. This can be done most effectively by borrowing from an HR department. Employee performance management processes are typically burdened by an inflation of too many excellent ratings. The way of HR people to deal with this is to ask for forced rankings of employees. In essence, the managers of two excellent employees will be asked to agree on which of the two employees is even more excellent than the other. We propose deploying the same principle for populating the performance axis of the TrueSRM framework.

Here’s how it might work: Initially, you would tap into the available supplier performance reports. You would then aggregate these reports across business units on a supplier level. If all business units are similar in size, no weighing is necessary. If there is a substantial difference in size and if business units do have significantly different requirements, appropriate weighing approaches should be introduced. This weighing could simply be based on the relative revenue of different businesses. But one might feel that this would lead suppliers to neglect the smaller businesses. This would be especially counterproductive if the smaller businesses are high growth and consequently need high-performing suppliers to support that growth. In that case, one could base the weighing on a pure arithmetic average of the scores in different businesses. Or, one may still base the initial weighing on relative revenue but then make adjustments for different growth prospects.

You would then calibrate the aggregated performance reports to achieve a normal distribution, or bell curve, over the performance axis. With this normal distribution, 5 percent of suppliers would fall into the high-performance category, another 5 percent would fall into low performance, and the remaining 90 percent of suppliers would fall into the medium performance category.

If you are reading closely, you see where this is going. In TrueSRM, we want to focus the company’s top management attention and resources on those suppliers that really matter. And the suppliers that matter are the top performers and the underperformers.

Top performers matter because they are the suppliers that have the most chance of helping the company shape its future. Not all top performers will be able to help shape the company’s future, and it is particularly hard to see that a supplier whose performance is not excellent will be able to do so.

Underperformers also matter because they drag the entire company down. They tie up valuable resources used fixing the delivery, cost, and quality issues they cause. Something needs to be done about underperformers.

The vast majority of suppliers in the middle may matter from a different perspective. But as long as we have untapped potential with high-performing suppliers, and unresolved issues with low-performing suppliers, they will not be the focus of attention. This is why it is usually counterproductive to start by overhauling and refining to the nth degree the approach to supplier performance measurement. The approach needs to be robust enough to enable the high performers and low performers to be triaged. It does not need to enable the 63rd percentile to be distinguished from the 62nd percentile, particularly given that suppliers provide different goods and services in any case.

Strategic Potential Axis

We have seen that populating the performance axis is tricky even when we do have data we can build on. Populating the strategic potential axis is far more difficult. Most companies do not have any established mechanisms to gauge the strategic potential of a supplier. Even worse, many companies are using the term “partner” in an inflationary way. Any high-performing supplier, or just a big one, will often be labeled as partner or even strategic partner.

While we cautioned about rebuilding the supplier performance evaluation system of a company when embarking on the SRM journey, we encourage doing just that for the strategic potential axis. There cannot be any TrueSRM as long as the key decision makers of the company are not aligned on what makes a supplier strategically important.

When we say strategic potential, we mean the relevance the supplier can have in relation to the execution of the company’s strategy. A supplier with high strategic potential should hold the key to a competitive advantage for the company. This competitive advantage might not yet be realized today because either the company has not yet understood how to tap into the supplier’s potential or because the supplier’s current performance blurs the view on the strategic potential.

The high-level strategic potential of a supplier can be measured across a number of indicators:

· Growth: Does the supplier offer capabilities that could improve the company’s value proposition for existing customers or generate sales with new customers? Examples would be wide geographic reach of the supplier or an excellent understanding of customer needs.

· Innovation: Does the supplier own or propose new technologies that could lead to breakthrough for the company’s products and services? Examples would be a supplier that has developed critical patents or conducted strategic mergers and acquisitions.

· Scope: Is the supplier relevant for the company across most business units? An example of such a supplier would be a true portfolio player that supports the company by supplying all of its divisions.

· Collaboration: Does the supplier demonstrate the right mindset in working with the company across different functional areas? An example would be a supplier that leverages its critical capabilities in an effective way.

For the introduction of the strategic potential axis, we suggest a fairly provocative approach. In contrast to the often inflationary use of the terms strategic and partner, in our view, the default strategic potential of a supplier should be low. We strongly believe that at least 90 percent of suppliers have very limited strategic potential to a company.

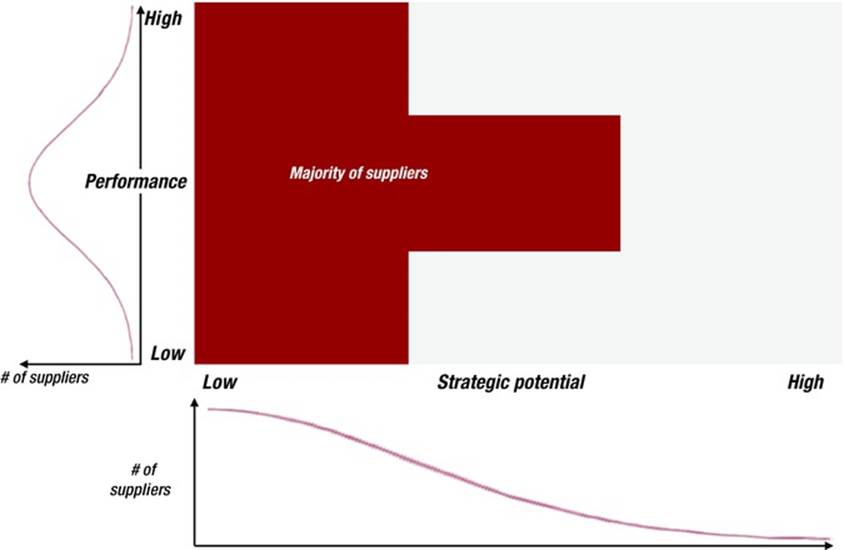

While populating the performance axis of the SRM framework is done in a bottom-up way, for the strategic potential axis we suggest doing it with a top-down approach. Top management should get together and determine the suppliers that have high or medium strategic potential. Overall, we would expect to find 2 percent of suppliers at most to have high strategic potential and 8 percent of suppliers to have medium strategic potential. In most cases, the high-potential strategic suppliers should amount to only a couple of handfuls.

The Framework

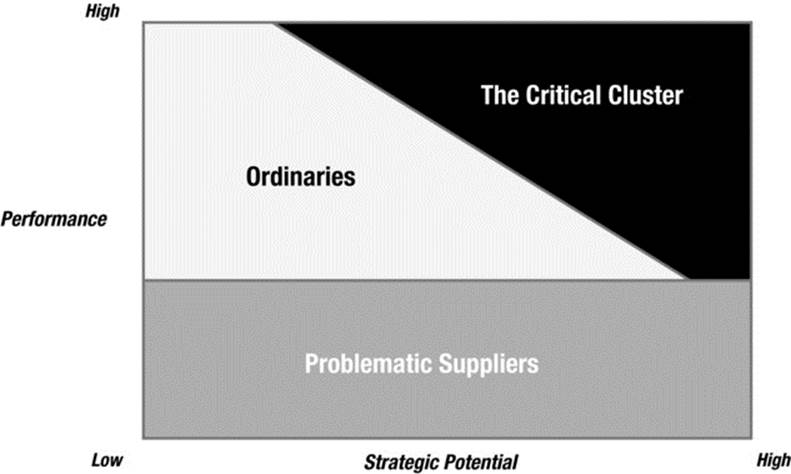

Looking at the overall picture in Figure 4-3, a pattern begins to emerge. Most suppliers will be center left in the portfolio, which means that they have average performance and are in mature business relationships. A limited number of suppliers will reside in the “interesting areas” at the corners of the portfolio. This leads to the question of how to interact with these suppliers.

Figure 4-3. The expected distribution of suppliers

Regardless of industry, company size, or a dozen other factors, suppliers tend to fall into three distinct camps: There are those in the “critical cluster” that can contribute to competitive advantage, with some nurturing of the relationship. There are the “ordinaries” that can provide needed but common products or services that could be purchased from many other sources. And then there are those “problematic” ones that have been useful sources of supply but pose serious problems that need to be fixed or the supplier replaced.

Managing supplier relationships is nothing new, of course. What is new is our system for recognizing what characterizes a supplier in relation to a company’s unique business objectives. What is the core nature of the relationship? How can it better serve the company’s success? What do the suppliers themselves want? And how do we communicate with them, both in terms of where they stand now and where we want them to be in the future? This last point is especially pertinent because supplier relationships are rarely structured in a way that guides internal conversations and planning, or allows for communication in actionable terms.

Identifying individual formulas or models that together characterize TrueSRM is the premise that drove the project team to develop nine ways to interact with suppliers. Each model gets to the heart of what makes the most common and effective supplier relationships tick while establishing expectations for what each relationship is capable of and laying the groundwork for mutual success. While there is no substitute for classic sourcing or the proficiency of our Purchasing Chessboard, our supplier relationship management approach is designed to identify and support those relationships that pose the greatest return on investment while considering the limited time constraints of many CPOs.

The Nine Relationships

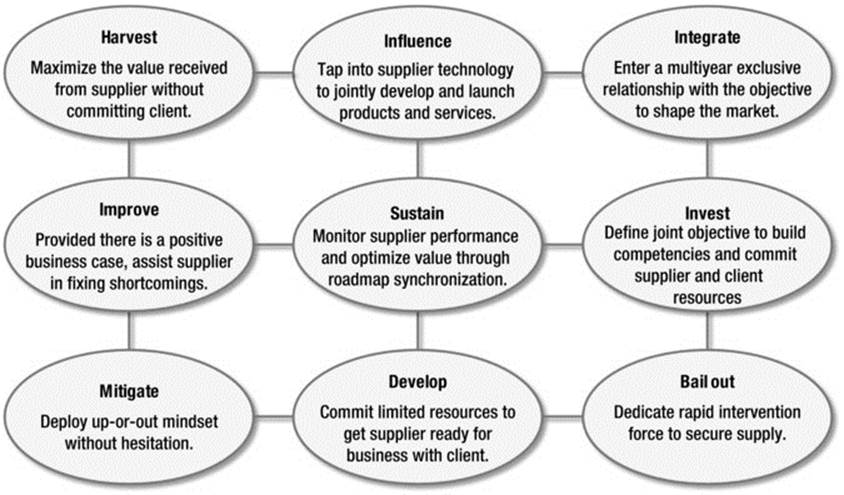

Figure 4-4 introduces the nine supplier relationship models in detail:

Figure 4-4. Nine interaction models

Critical Cluster: The Relationships to Nurture

The first category under our microscope, the critical cluster, includes the three types of suppliers that offer the most promise. Whether they are the vendors that already have a great relationship with you, or the ones that clearly could have one with a little work, these relationships are the valuable few that are worth time and attention.

Integrate: Worthy of Commitment

In this box, we find the Integrate model, where the two organizations have goals that are genuinely integrated and they work together as partners. To put it colloquially, this is a partnership with a capital “P”. Although an often-overused term in business, this type of true partnership is rare and is based on a multiyear, differentiated, and comprehensive relationship between you and your supplier to build an ecosystem that shapes the market. The supplier chosen for this model should be in your sweet spot: its performance needs to be flawless, and it needs to hold the key to making you a formidable competitor by creating opportunities to grow revenues and profits while jointly shaping or reshaping the industry.

Influence: Joint Development of New Offerings

Suppliers that fit the Influence model in this box deliver nearly perfect products or services. What sets them apart is that they offer the potential for innovation by working with you to jointly develop new products or services. This factor shapes your relationship with them. These suppliers often dominate an industry, as they are the crucial few that a company and its competitors rely on. In turn, they do not favor any one customer, and in the case of monopolistic suppliers, are required by law not to do so. The downside, of course, is that it is nearly impossible to outpace your competition by working with these suppliers. What’s more, mismanage this relationship and you could alienate these suppliers enough that you fall behind competitors that may be better at handling their relationship with the same supplier.

Invest: Promise of Capability

Does your company have suppliers that offer great ideas and innovations but then stumble in some basic areas, such as providing continuous supply or consistent quality? Those suppliers fall into the Invest model. A great future can be had with these suppliers—as they ultimately could reach Integrate status—but their potential for this rests on the relationship you build with them now and the extent to which they respond. Ideally, an Invest supplier will aspire to Integrate status and will invest with you in building capabilities to achieve this title. Here, we recommend nurturing the relationship by investing time, money, and resources in developing the supplier’s capabilities to meet your needs. The best candidates will make capability building a top priority. Be forewarned, however, that some suppliers may spurn the help, believing that you are attempting to make them “captive” and cut them off from wider market opportunities.

Ordinaries: The Widget Providers

While the three supplier types that fall into the ordinary camp are generally more numerous, don’t let their average status fool you. There is strength in numbers here. With more of these dime-a-dozen suppliers in your fold, having a keen understanding of what makes these relationships tick, and a simple set of tools for maintaining or incrementally improving their performance, can have sizeable positive results for you.

Harvest: Highly Productive But Still Needs Cultivating

The Harvest model represents a well-functioning position for both parties. The company receives exactly the type of products or services it needs from the supplier. These things are nearly perfect, in fact, and support the company’s competitiveness. For you and the supplier, this relationship is virtually hassle-free and ties up few resources. It may seem to function on its own, and that’s exactly where both parties need to focus. Complacency should be the red flag here. Great performance could be mistaken for a great partnership. We recommend not using the term “partner” loosely, because it can lead to assumptions that nothing needs to be changed. Low investment of resources can communicate that you don’t overtly value this relationship and that if the supplier falters, it could be dropped. The Harvest supplier’s vulnerability, then, and the absence of discussion about maintaining performance, can create tension that negatively influences interactions between the parties.

Sustain: Worthy of Continuous Improvement

You probably work with a number of Sustain suppliers. Their performance is average, but aspects of this type of relationship place it above the ones you have with most suppliers, usually because you need these relationships to endure. They do not need major fixes or warrant significant investment. However, undertaking incremental improvement to capture more value and move performance toward world-class levels can usually benefit you.

Improve: Shortcomings Need to Be Addressed

The majority of your suppliers are likely to fit in the Improve category. They perform at a level similar to that of a Sustain supplier, but with shortcomings. The key difference is that should they fail—especially repeatedly—you would be more likely to replace them than you would a faltering Sustain supplier. The Improve relationship can feel unstable for both you and the supplier as a result. Instead, to profit from the relationship you will learn to turn the unknowns into opportunities by helping the Improve supplier to raise performance and move toward Harvest status.

Problematic Suppliers: The Serious Fixes

Rather than rue the day you hired certain suppliers that have become problematic, take a close look at what has gone wrong and learn from everyone’s mistakes. Indeed, this is the time to contain the damage. It’s also a great opportunity to repair relationships that warrant the investment, or at least keep the lines of communication open should you both go your separate ways but later find that things look better.

Mitigate: Need to Be Disengaged on Good Terms

Sometimes, it just doesn’t work out. The Mitigate supplier has significant ongoing issues with delivery, cost, or quality, for example, and it’s time to replace this source with one that is more promising. The risks and consequences of doing this then need to be mitigated. Relationships that reach the Mitigate stage are easy to transition out of when the failing supplier is small or the business is simply structured. But when there are multiple lines of business, numerous product segments, or big outsourcing agreements with a long-term supplier, replacement becomes a challenge. Paradoxically, the quality of this relationship—even though it is ending—is one of the most important supplier interactions to maintain at a level of openness and clarity while you are still working together.

Develop: Candidates for the Ideal Source

To establish a competitive advantage and operational benefits where none currently exist, consider building a Develop relationship with a supplier whose current performance is poor and needs to be addressed. This should be a hand-selected vendor with lots of potential for working closely with you to identify opportunities across its value chain and yours. Reach out to your in-house cross-functional teams to identify viable candidates that are currently not ready for prime time but have the basic potential to become star suppliers. There are numerous examples of Develop suppliers that become key sources in well-managed relationships that last for years. Consider, for example, the many manufacturers that nurture low-cost country suppliers, providing technology or engineering assistance to get them up to speed as component suppliers.

Bail Out: Stepping In Is Necessary

A major supplier commits an egregious error or a chronic problem suddenly requires triage. This is the abrupt formation of the Bail Out relationship. The situation can significantly jeopardize business by threatening supply.

The immediate goal is to stabilize the performance of the supplier, whose reaction will be hard to predict. Long term, look to learn from the problem to avoid future bail outs with this supplier. It may seem counterintuitive, but this is a relationship that will likely be maintained, particularly with important suppliers. The Bail Out relationship itself should be brief, rarely occur, and be regarded as a temporary step toward improving the overall supplier relationship.

Heartland Develops TrueSRM

Meanwhile, back at Heartland Industries, Thomas and Laura were grappling with their recognition that they needed an approach for TrueSRM.

After her conversation with Thomas following the final workshop, Laura went back to her office and pondered the situation. She realized that, as CEO, Thomas did not want to be concerned with all the details of every supplier. Of course. That was a given. As CPO, she herself could not be concerned with every supplier. Heartland had several thousand suppliers globally, and this was unlikely to change radically. She also pondered what Thomas had meant by “managing our interactions holistically with suppliers.” The word holistically caused her to pause. She felt that it made sense. Heartland needed to set up SRM in a way that enabled it to orchestrate all dimensions of a supplier relationship—performance, cost, behaviors, risk, and so forth. But this had to be tailored to the specifics of the relationship. Otherwise, this would be far too unwieldy and resource intensive for the business to execute. There needed to be some form of differentiation that the business could implement.

Laura had seen segmentation approaches before, but she had not seen one that really provided a basis for managing interactions in the differentiated way that she sought. One approach that she had seen talked about had you identify “strategic,” “core,” and “noncore” suppliers. This had always led to lots of debate about what exactly a strategic supplier was. Previously, she had seen the word strategic used as a proxy for “large,” which missed the point. Marshfield, which had just tied up with Calbury Industries, was not a particularly large organization.

Laura sensed that many of the most valuable suppliers, who could bring exclusive innovation, were indeed likely to be small, entrepreneurial, and lacking “pedigree.” She thought of digital marketing, for example, as an area that classic advertising agencies were still grappling with. Heartland might prefer not to deal with the established players at all in this space and instead bypass them. “Young start-ups might just be able to bring what the business needs as our suppliers,” she mused. “They might not be operationally so robust, though.” Clearly, there is a big distinction to draw between current performance and strategic potential.

“Conversely, some suppliers perform well but lack strategic potential,” she thought. “Best not to spend too much time on them.” She wondered about what to call them. “Well, they certainly are not particularly special suppliers. They are actually quite ordinary, really. Maybe then we should call these ‘Ordinaries.’ Most of our suppliers belong in this camp.” Others, she knew, perform well and have great strategic potential. Marshfield might have belonged in this camp. These are suppliers that need strong attention—including personal attention from Thomas. They are far more special. “Probably better not to call them special, though. They are critical to the business.” She now had a name for them. “That’s it—these are the ‘Critical Cluster.’ Then, there are other suppliers who basically give us problems. That’s an easy name. They are the ‘Problematic Suppliers,’ who have either performance issues, limited strategic potential, or both. Big danger if we spend too much time on these suppliers. Although the ones with poor performance but strong strategic potential might be worthy of being nurtured. We would need to make our bets carefully.”

Laura really felt she had made progress in how to work through to TrueSRM. It was close to the end of the day now. She got her Stylus out and started to draw on her iPad. She labeled the vertical axis “Performance” and the horizontal axis “Strategic Potential.” [Figure 4-5.] She then drew the three clusters. She placed the Critical Cluster on the top right, Problematic Suppliers horizontally across the bottom, and Ordinaries to fill the rest of the screen. She decided to go back to see Thomas. “Time for action,” she muttered under her breath as she left her office.

Figure 4-5. The three clusters

Thomas’s office door was wide open and Laura walked in. She showed him what she had done on her iPad and emphasized how it would help them to prioritize executive effort.

“So we focus on how well they perform now versus their potential value. Makes sense,” he mused. “I just wonder whether three clusters is really granular enough to be actionable.”

“You may be right,” said Laura. “Shall we sketch it on the whiteboard and think about it?”

Thomas nodded. Laura drew the two axes. She added the three clusters. They focused first on the top right-hand corner.

“At the very top right will be the closest relationships,” said Thomas. “That’s obvious.”

“The true partnerships,” added Laura.

“Yes,” Thomas agreed. “But, I am not sure we should use the P word. It’s so overused that I think it is often meaningless. These are really situations where we want to achieve some close form of integration between our business and theirs. Maybe we call these Integrate.”

“Right,” Laura replied. “The bottom-left corner is easy too. That is where we want to get out of an unsatisfactory relationship without breaking too much china. So, let’s just call it Mitigate. The extremities are probably the easiest ones. What about the top left?”

“That’s interesting,” said Thomas. “A high-performing supplier where we do not really value the strategic potential. It’s the sort of supplier we sometimes see in noncore categories. They can be really good at what they do, but we’d only notice if they suddenly stopped. This is the type of relationship where we just sit back and harvest the good work they do. Let’s call these Harvest.”

“Great,” remarked Laura. “Bottom right are the suppliers we value a lot, but their current performance is a big issue and can stop us shipping product. These are the situations where we need to step in ourselves to fix things or to bail the supplier out. So, let’s call these Bail Out.”

“I agree,” Thomas replied. “What about the middle of the board? That feels like the next logical place to go. In the very middle, we have relationships that we value. But, they have only average or so-so performance. We probably need to maintain or sustain these relationships, but they are not overly exciting for us.”

“So, we can call them Sustain,” suggested Laura.

Five interaction models had now been created.

“Now, for the more challenging ones between the extremes,” proceeded Thomas. “Let’s start top middle. These are strong suppliers that we need to be successful, but that we will probably never be in a position to integrate with.”

Laura interjected. “In these cases, our aim should probably be to influence them to provide innovation on a limited scale.”

“So maybe we should call these Influence,” proposed Thomas. “What about the right middle?”

“There we have middling performance but high strategic potential. So, perhaps these are suppliers where we may need to establish some form of joint action or investment with to create something special between us. It could be a new capability that is greater than either of us already has, or a new facility for example. Perhaps we call that Invest,” suggested Laura.

“That works,” said Thomas. “Good, seven models defined. What about the bottom middle?”

“Poor performance, reasonable relationship value. Sounds like these are suppliers we want to keep but something needs to happen so they can meet our performance needs. We probably need to devote some effort to help that happen, but without overdoing things.”

“So we can call these Develop then. One more left. Middle left.”

“Low relationship value and middling performance,” was Laura’s assessment. “No obvious reason why we would invest much in such a relationship. These are suppliers where we need them to step up more if they are to continue with us. They need to do better.”

“We can call them Improve,” Thomas suggested. “Great, we have a 3 x 3 matrix. Consultants usually do 2 x 2. We have gone one better,” he joked. “Where do you think most suppliers sit in this framework, Laura?”

“Oh, I think mainly toward the left. There will be very few in the top right. But, the top right is where we ought to focus our attention.”

“Do you think we should do that properly? I mean, do we devote most of our attention to the few suppliers in the top right? Or do we dissipate it elsewhere?”

“Gosh. I am not sure. Maybe not.”

“You might want to get some analysis done. I would be interested in the result.”

“I will do that,” agreed Laura. “I will also get to work on how we can use this.”

Categorizing Suppliers

In this chapter, we have introduced the TrueSRM framework. This framework is based on differentiated interaction models that are constructed by considering the performance of a supplier and its strategic potential. We have explained that for most companies the existing supplier-performance-management approach is fit for the purpose of enabling the top performers and the poor performers to be differentiated from the majority in the middle. Conversely, most businesses do not have a robust approach in place to determine strategic potential with sufficient rigor. We strongly recommend a top-down approach to this that typically leads to only a very small number of suppliers (often just a couple of handfuls) being classified as high potential.

In the next part of the chapter, we introduced the nine different interaction models that this framework gives rise to. These are discussed as being within three separate clusters. Deploying these models effectively for different suppliers is critical for really bringing TrueSRM to life.

The next three chapters are structured by cluster. For each interaction type, we will explain the key characteristics of suppliers, the types of behaviors that need to be undertaken, and the best ways to work with the suppliers. We will also outline the preferred governance approach and provide a case study example. As we do this, we also continue the story of Heartland as they put their TrueSRM program into effect by deploying the different models.