Supplier Relationship Management: How to Maximize Vendor Value and Opportunity (2014)

Chapter 8. Putting Supplier Interaction Models to Work

Start Reaping Benefits

Now that we have introduced the overall SRM framework and the nine supplier interaction models, it is time to discuss how to make it happen. Accordingly, in this chapter we discuss a number of themes.

First, we outline the dynamic nature of SRM. The TrueSRM framework is not static. Suppliers can change position over time. We outline how this can be used to your advantage in order to give suppliers aspirational messages. This links to the concept of primary and secondary models—where the secondary model is the position that the supplier could reach or fall back to depending on performance.

We then go on to discuss the key operating-model elements that are needed to bring SRM to life. This includes the need for top-down decision making to determine strategic potential and for bottom-up input to evaluate performance. Governance models then need to be differentiated by interaction model, and resources need to be allocated to different suppliers according to their positioning.

Following this, we step back to consider the changes that take place once SRM is implemented and how success needs to be measured. In this respect, we favor a focus on competitive advantage rather than micromeasurement of benefits, which one often sees when implementing category-sourcing strategies. In fact, we see SRM as very distinct from category sourcing, and we therefore devote some time to dispelling some common confusion as to the difference between these approaches.

Having discussed these points, we then go on to talk about how to get started and then how to make SRM sustainable once you have begun. We also catch up with how our friends at Heartland are getting on with SRM implementation and consider the key factors that have driven their success.

A Dynamic Framework

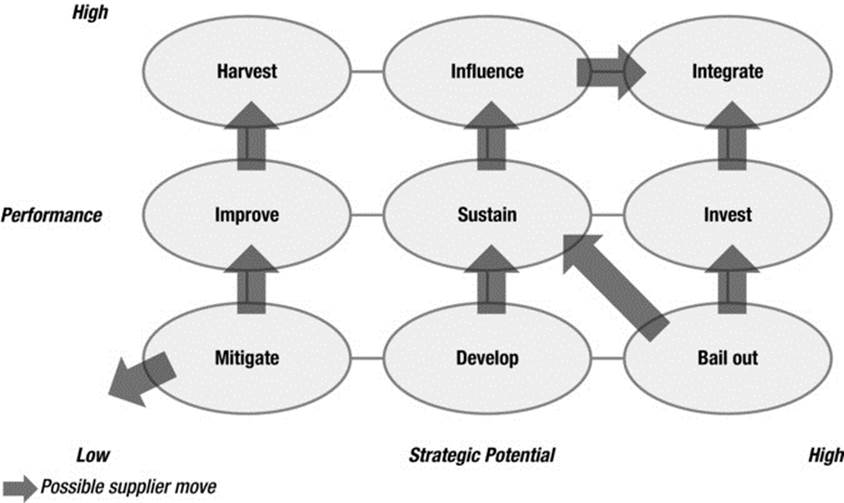

The performance of suppliers varies over time, so a supplier’s vertical positioning in the framework will vary as well. Also, the strategic potential of a supplier can change. Let’s look at moves between interaction models in more detail.

Onboarding New Suppliers

Suppliers that are new to a company have no performance history. Typically, when onboarding new suppliers, companies apply good judgment and treat them with extra caution. Often this is sufficient to ensure a smooth onboarding without too many operational issues. Yet even so, serious shortcomings shown by new suppliers sometimes escape management’s attention and lead to undesirable consequences. These include delivery shortages or quality problems. Our recommendation is to initially put all new suppliers with limited strategic potential into the Mitigate category until they have proven that their performance meets the expected level. If a new supplier in that category shows issues, it should be phased out without hesitation.

If you identify a promising new supplier that could make a difference, place it in the Develop category and dedicate company resources to bring it up to speed as quickly as possible.

For the rare diamond in the rough that is found occasionally, we recommend you go into Bail Out mode from day one. This is clearly a valuable relationship that you do not want to ruin by avoidable performance issues. The Bail Out mode will enable you to get through these challenges and ensure that the company gains the projected competitive benefit from working with this supplier.

Supplier Moves You Are Driving

Not every model in the framework has a logical path to a neighboring model. Upward moves are perfectly possible and always desired. Suppliers can improve their performance with or without the company’s support, performance you can recognize in the regular performance reviews.

The horizontal position in the framework is nearly locked in by the particularities of the supplier’s business. Moves to the right require the supplier to significantly change its nature. The only possible move in this direction that we expect to see leads from Influence to Integrate. Think about a supplier who defines an industry standard. If that supplier is ready to provide products and services that allow you to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage, we would place it in the Integrate box. We are seeing elements of this behavior in several industries.

In addition to the vertical and horizontal moves, there is one possible diagonal move. If a high-strategic-potential supplier falls into a Bail Out situation, you have two options: Either you improve its performance so that it justifies its high potential or you aim to make the supplier less critical. Creating a viable alternative by qualifying another supplier to take over a portion of the volume share would move this supplier to the Sustain model. In that position, the supplier will be given the opportunity to recover its standing.

Finally, there is one move leading from Mitigate out of the framework altogether. This is because you are terminating business with that supplier unless and until there is a compelling reason to work with it again.

All of these supplier moves are illustrated in Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1. Movement within the supplier relationship model

Primary and Secondary Interaction Models

The notion that the TrueSRM framework is not static extends to the question of whether or not a supplier can fall into more than one interaction model at any point in time. Generally speaking, the idea of the SRM framework is to map the supplier as one entity and not break the mapping down to a category level.

While this is the rule, when communicating the framework and the positioning to suppliers, you should aim to send aspirational messages. Compare this to the annual feedback discussion you have with an employee. In this discussion, you would not tell the employee that she is locked into her current role and that the next level is out of reach. In order to allow for aspirational messages, we therefore introduced primary and secondary interaction models.

Following the logic of the moves introduced above, the aspirational messages should generally trend upward. For example, a supplier in Improve that is doing really well across several categories could receive the following message:

You know, we are really quite happy with your performance lately. Across categories A, B, and C you are actually best in class. We specifically like your proposal to become your launch customer for the new product technology in category A. In our SRM framework, we have now added Influence as secondary interaction model to Sustain. In order to get you into Influence for good, you would need to fix the delivery issues with the mainstream categories D and E.

Obviously, the secondary interaction model also can be used to send messages in the opposite direction when your happiness with a supplier is decreasing:

We have had you in Integrate for several years now. Our partnership has yielded several game-changing products and we have always appreciated your willingness to build a winning ecosystem with us. However, over the past months we have gotten increasingly concerned about a change of attitude that might be best summarized as complacency. You have let too many deadlines slip and the product quality was not always what we had expected. We want you to get more focused again, and in order to emphasize this message, we are adding the secondary interaction model Invest to our relationship.

Let us now take a look at who is preparing and delivering these messages.

Overarching SRM Decision Making

No, we don’t want to introduce another administrative body. We firmly believe that corporate cultures are already overburdened with committees of all kinds. What we intend to do is to take existing cross-functional decision-making bodies and use them for SRM purposes.

In essence, SRM requires two types of decision making at the corporate level. One is bottom-up decision making regarding the evaluation of supplier performance. Another is top-down decision making that determines the strategic potential.

For evaluating performance, most companies will have cross-functional teams in place. The challenge is that they act in isolation while SRM needs a comprehensive perspective. In Chapter 5, we discussed segmentation criteria and forced ranking in detail. Here, we want to limit the discussion to who is actually making these slotting decisions. We recommend having as much of a big-picture view as possible. So, if at all feasible, the company should force-rank all of its suppliers. This will work for companies that have relatively homogeneous lines of business. For those companies, cross-functional teams should spotlight the exceptions to their leaders, meaning the really-outstanding and really-poor-performing suppliers. The leaders should then get together to assess these exceptions. With this approach, 90 percent of suppliers will fall in the middle category and debate will be limited to 10 percent of suppliers, normally a doable task.

For companies with a diverse set of businesses—think ThyssenKrupp with steel mills, shipyards, engineering services, automotive suppliers, and elevator makers—force ranking all suppliers will not make sense. For these types of conglomerates, we recommend applying performance ranking at the level of each individual line of business, or for each distinct subsidiary.

Determining the strategic potential of a supplier should be done top down by the cross-functional leadership team. Once a year, the leaders get together and decide which of the suppliers have a medium or a high strategic potential. Again, we assume that less than 10 percent of suppliers will fall into these two categories and therefore that the task will be perfectly manageable.

![]() Note When determining the strategic potential of your suppliers, remember that in most cases only 10 percent of them will be in a position to help you gain competitive advantages.

Note When determining the strategic potential of your suppliers, remember that in most cases only 10 percent of them will be in a position to help you gain competitive advantages.

Governance Models by Supplier

For suppliers in the Harvest, Improve, and Sustain categories, not much will change. You will continue measuring their performance periodically and provide feedback. While their positioning in the framework will not be a secret, you will not proactively communicate it. Other than working to improve their performance, there is not much the suppliers can do to change their positioning.

Suppliers that fall into the Mitigate, Develop, and Bail Out interaction models will not be engaged in a broader discussion of their relationship. Time is often critical and matters are urgent, so specific business needs to improve performance or address failings will dominate the agenda.

Where things will change significantly is in the Influence, Integrate, and Invest interaction models. You will proactively inform suppliers in these categories as to where they stand, develop clear roadmaps and account plans, and drive aligned agendas through joint steering committees. In particular:

· For Influence suppliers, you will focus on formalizing the process to bring into sync your respective product, technology, and service roadmaps. In order to make this happen, a cross-functional steering group will not only ensure smooth communication with the supplier but also establish consistency across Procurement, Engineering, and Product Marketing. With this fine-tuned approach, you will be able to win where it matters.

· Invest suppliers will initially receive a lot of feedback from you. What used to be isolated performance reports will be condensed into a thoroughly researched performance gap analysis. This analysis will be shared with the supplier’s senior executives, together with clear performance targets. You will assign program managers to drive improvement and dedicate substantial executive attention to guiding the supplier in the right direction.

· Working with Integrate suppliers will be the masterpiece of your SRM efforts. First, you will develop a mission statement together with the supplier, specifying what it is that you want to achieve jointly. Then, you will define a step-by-step roadmap that describes how the supplier can earn the right to exclusively “own” a product market segment. A binding incentive mechanism will ensure that your objectives and those of the supplier are fully aligned, and that both parties act as partners with an entrepreneurial spirit. Finally, a joint executive leadership team will oversee the product market segments in scope from a holistic, end-to-end perspective.

Roles in SRM

As we have seen, each of the nine supplier interaction models has its specific governance structure. There are several common denominators, though, that are relevant across the entire SRM framework.

First and foremost, the old principle of presenting one face to the supplier should be followed. We know it is easier said than done, but if suppliers are able to put a key account manager in place, customers should certainly be able to appoint one relationship owner as well.

![]() Tip The supplier should, ideally, deal with one customer point person. Whom you choose, however, is critical.

Tip The supplier should, ideally, deal with one customer point person. Whom you choose, however, is critical.

The position of the supplier in the SRM framework will largely determine the seniority and functional affiliation of the relationship owner—the primary “go to” person who is responsible for managing the relationship with the supplier. For suppliers that are in Harvest, Improve, and Mitigate, the relationship owner will most likely come from Procurement. Given the low strategic potential, involvement from other functions will be limited. The seniority level of the relationship owner will correlate with the spending that is attributed to that supplier.

Who Is the Best Relationship Owner?

For suppliers in Develop, an engineering or manufacturing representative might be appointed as relationship owner. Typically, these functions have the strongest vested interest in bringing this promising new supplier up to speed and making it ready to bring new products and services to the market.

For suppliers in Sustain, the relationship owner will probably come from the function that has the highest level of interaction with that supplier. If, for example, you are dealing with a marketing-and-advertising firm, it would come naturally for a senior marketing executive to own the relationship.

Moving on to Influence, the choice will vary by industry. If it is about a supplier that defines an industry standard, the relationship might even be owned by the CEO. This will, for example, be the case for an airline, where the chief executive will own the relationship to Boeing and Airbus.

In Integrate, owning the relationship will be highly time-consuming given the complexity of the relationship and the associated cognitive load. It is unlikely that a candidate at the top executive level can be freed up from other duties to attend to the required extent; therefore, the relationship owner will probably be a mid-ranking executive who is highly respected internally and passionate about building a game-changing ecosystem.

For Invest suppliers, the relationship owner will mostly guide the supplier in comprehensive programs to build capabilities. Given the nature of this task, the relationship owner will most likely have a technical background.

Bail Out suppliers follow their own rules. As the Bail Out will be governed by a task force or tiger team, the leader of this team will take over the ownership of the relationship from the regular relationship owner for the duration of the bailout.

Maintaining Consistency in Your Message

Once the consistency in the communication channel is established, you need to ensure consistency in content. Today, most companies do have supplier evaluation processes established. Regardless of whether they are as structured as we suggest in Chapter 5 or not, sending confusing messages to suppliers is a common pitfall. We have seen quarterly supplier evaluations fluctuate so wildly that even the most well-meaning supplier will not be able to make any sense of the feedback it receives.

As a fix, we suggest making the supplier evaluation simple and focusing it on a few key criteria that really matter. Also, the cross-functional team that produces these evaluations should be characterized by continuity. The relationship owner should have the final say in the rating and feedback the supplier receives.

Employing Account Plans

With consistency in communication and content established, the cross-functional team needs to align on where to drive the supplier. Account plans have been found useful in this context. The account plan describes at a high level where the relationship with the supplier should be heading mid- to long-term. Once this account plan has been agreed upon by internal stakeholders, it is usually shared with the supplier. It is good for the supplier to understand what its customer’s intention is and what it could get out of the relationship if this intention is fulfilled.

Meetings with Suppliers

This leaves the final communication topic of regular meetings with suppliers. Suppliers in Harvest, Improve, and Mitigate do not require large formal meetings, and can be dealt with more on an ad hoc basis, such as when the sales representative happens to make his usual call.

For all other suppliers, you should provide a great deal of attention to the preparation and execution of meetings. We have seen quarterly meetings deteriorate into a ritual that can be best compared to going to mass on Sunday. The representative for the supplier comes to the sermon and listens, confesses the company’s sins, promises to do better in the future, walks out, and continues with business as usual. This is a massive missed opportunity. It takes a great deal of effort and money to get key stakeholders from both parties into one room. As a general rule, the relationship owners from both sides should agree on the key topics to be covered in the sequence of meetings over the next year or so, based on the account plan. Then, the functional teams from both sides should be tasked with preparing meaningful status reports and outlooks with regard to the progress vs. the account plan. Bringing this more forward-looking mindset into meetings with suppliers adds a lot of value to the relationship.

Where to Put Resources

As already hinted at in the previous paragraph, our SRM framework will lead to a quite substantial reallocation of resources. Among other things, our aim is to help companies to put their resources where it really matters. Today, in most companies the available resources are spread relatively evenly across suppliers.

We are suggesting a highly asymmetric allocation, starting with managing at arm’s length the vast majority of suppliers that reside in Improve and Harvest. Managing these suppliers can tie up a lot of resources, but if you are brutally honest, you will see there is little to gain by spending as much time and effort as you do. This is why we recommend having relatively junior procurement people own the relationships with these suppliers.

Suppliers in Mitigate can still be managed by relatively junior procurement people but will require more of a time commitment. This is why we recommend making decisions swiftly. Having a supplier hanging in this interaction model for more than a couple of months would definitely be wrong.

![]() Note Suppliers shouldn’t reside in the Mitigate category for more than a couple of months. By that point, if you have done your job properly, they should be moved up or out.

Note Suppliers shouldn’t reside in the Mitigate category for more than a couple of months. By that point, if you have done your job properly, they should be moved up or out.

The heavy resource allocation should be at the opposite end of the SRM framework—in Integrate, Invest, and, if needed, in Bail Out. With Integrate suppliers, you should aspire to build a winning ecosystem that will allow game-changing moves. It is evident that these relationships should be prioritized over all others and have the first call on any available resource. This is where the company will win or lose ultimately.

For suppliers in Invest, the resource allocation should be more cautious. After all, we believe these suppliers could become great partners but we still need the proof of concept. Therefore, the emphasis in Invest is to guide the investments of the supplier in terms of funds and talent allocation without committing too many of the own resources.

Bailouts will drain substantial resources when they occur. But there is little we can do about this. Our recommendation is to front-load bailouts by sending people to be there (physically) without hesitation. The old proverb “Better being safe than sorry” still applies and we have seen that too many companies hesitate in the critical early days of a bailout. These highly nonstandard situations cannot be solved via e-mail and phone calls; having boots on the ground early makes a big difference.

Suppliers in the middle three interaction models should receive resources but with caution. For suppliers in Influence, the key question is, “Can they be influenced?” If the supplier is ready to engage in collaborations that lead to a tangible competitive advantage, committing resources makes perfect sense. But all of us have seen the skillful efforts of suppliers that define an industry standard that only maintain the status quo. Accepting invitations to conferences, dinners, and golf courses can be a useful way to build a rapport of trust and mutual understanding. But these things have to provide a yield. If nothing tangible has surfaced after a year, it should become clear that the supplier does not want to engage under the terms of this interaction model. After this realization, it seems appropriate to sit down with the supplier and explain that you are scaling back the relationship to Sustain.

In Sustain, the resource requirement should be minimal. Efforts should be limited to reminding the supplier of the growth potential that would open up if it improved its performance.

Suppliers in Develop will receive quite a lot of support and resources. One way to justify this commitment is to have the supplier pay for it. A best-practice example from the automotive industry is to establish supplier development teams that act like external consultants. These teams have daily rates that get charged to the suppliers, who are encouraged to use these services. A positive side effect of this practice is that a supplier will take services it has to pay for more seriously.

What Changes for Suppliers

With the SRM framework in place, everything changes for suppliers. Imagine your company having one common language to define supplier relationships, alignment across functions, alignment across lines of business, and alignment across hierarchy levels! In this scenario, we will see winners and losers among suppliers.

Those suppliers that so far have dedicated most of their time to playing games, to finding the weak link in your organization will lose under these new terms. Their scheming and politicking will be brought to unforgiving daylight and they will have little time to adjust.

The winners will be suppliers that always had good intentions but were frustrated by conflicting messages and lack of clear direction. They will finally find a framework they can plug into and find their spot to best add value.

HOW TO MEASURE THE SUCCESS OF SRM

SRM cannot be measured in terms of cost savings. This is what category-sourcing strategies are about. At the highest level, the success of SRM can be measured by the incremental competitive advantage that can be attributed to suppliers. Competitive advantage will mean different things to different companies, but it can manifest itself as follows:

· Successful product and service innovations that have been brought to market and helped the company gain market share

· A higher profit margin due to higher price levels that can be achieved in the market and those due to overall reduced cost of goods sold

· Higher availability rates and shorter delivery lead times

· Better product and service quality, better and easier service, and happier customers

How SRM Relates to Category-Sourcing Strategies

In the process of developing the SRM framework, we have noticed wide-ranging confusion about the distinction between SRM and category strategies. In some literature, SRM is even defined as the implementation stage of a category strategy.

For the following comparison of SRM and category strategies, we are referring to the Purchasing Chessboard as the standard framework for developing category strategies.

As discussed in earlier chapters, the Purchasing Chessboard was developed by A. T. Kearney consultants in 2008 and has since been applied by thousands of companies across all industries and continents. The idea behind the Purchasing Chessboard is that category-sourcing strategies should be based upon considerations around demand power and supply power.

A company has a high demand power if its spending for a certain category represents a significant portion of the overall supply industry revenue in that sector. Additional factors that increase demand power are the opportunities for innovations that suppliers can draw from working with the company and the image boost a supplier would get from having the company on its reference list.

Similarly, a supplier has a high supply power if its revenue within a certain category represents a significant portion of the overall supply industry revenue in that sector. Additional factors that increase supply power are the ability of the supplier to drive innovation for the category and to create a pull with the company’s customers (think of “Intel inside”). Suppliers that own critical patents and are monopolists in a certain sector enjoy the highest supply power.

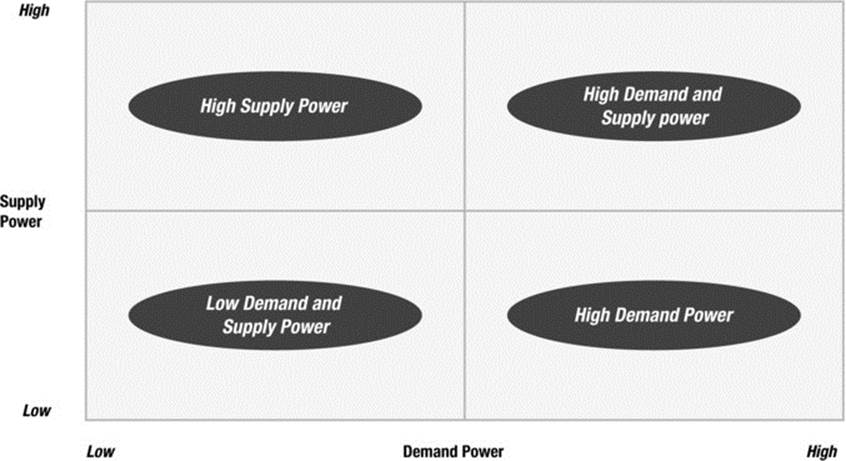

The Purchasing Chessboard is defined by two axes, demand power and supply power (Figure 8-2). At the highest level, the chessboard is segmented into four quadrants:

· High demand power: An example is a big carmaker (e.g., Volkswagen) that buys forged parts. There must be hundreds, if not thousands, of forged-part manufacturers throughout the world, and out of those there must be at least several dozen that are qualified to meet Volkswagen’s quality and volume requirements. In this case, Volkswagen is a buyer in a position of overwhelming power vis-à-vis its forgings suppliers, and it is able to exploit competition among its suppliers to its own advantage.

· High supply and demand power: If Volkswagen now wishes to buy engine management systems from Bosch, the situation is completely different. In many segments, Bosch holds a de facto monopoly. Nevertheless, Bosch is just as dependent on the big carmakers as they are on Bosch. In this case, securing joint, long-term advantages is unquestionably in the interest of both parties.

· High supply power: Even the demand power of a big carmaker has its limits, especially when oligopolistic market conditions prevail. A good example is the purchasing of traded commodities, such as platinum for catalysts. While Volkswagen certainly purchases a large quantity of platinum, it is fully dependent upon the quoted prices of metal exchanges. Companies confronted by high supply power will consistently strive to bring about fundamental change in the nature of the demand in order to free themselves from the control of the supplier.

· Low supply and demand power: An example of low demand power on the part of a big carmaker is air travel. The situation is more balanced than in the preceding example, however, since deregulation of the airline market has actually produced results. Along with negotiating discounts, a key question to ask in this context is whether traveling by plane is necessary or whether it could be avoided altogether. Thus, the company is largely able to steer its own demand.

Figure 8-2. The Purchasing Chessboard: 4 Basic Strategies

The four quadrants of the Purchasing Chessboard also represent its four basic strategies—leveraging competition among suppliers, seeking joint advantage with suppliers, changing the rules of the game, and managing spend. These are shown in Figure 8-2.

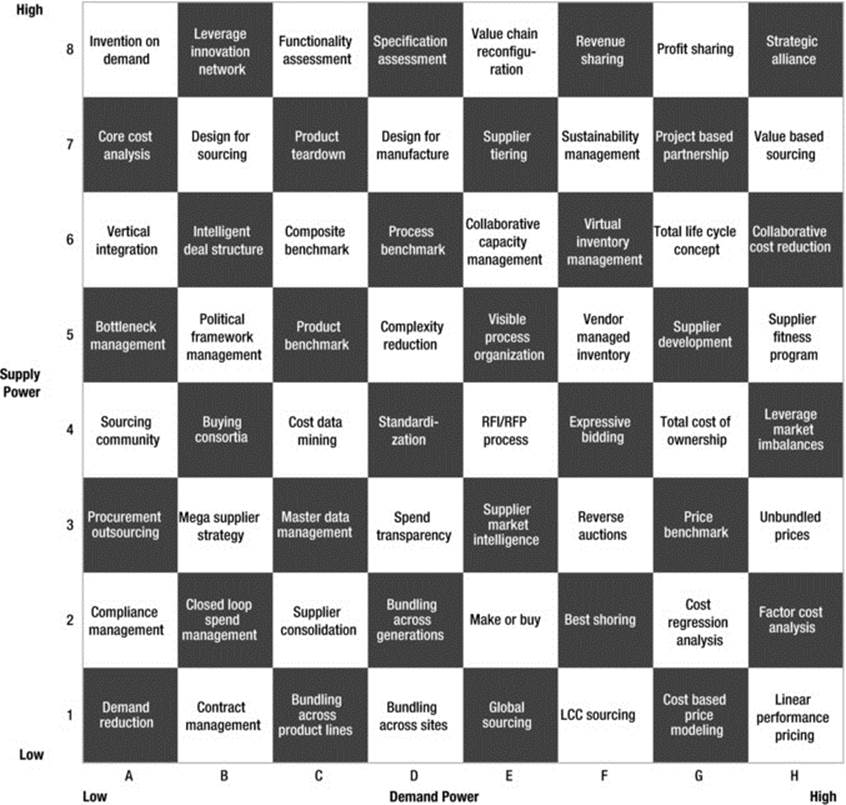

The most detailed version of the Purchasing Chessboard is comprised of 64 detailed methods—16 associated with each basic strategy. This is the one typically in use by procurement executives who are developing category strategies with their teams. The detailed version of the Purchasing Chessboard is shown in Figure 8-3.1

Figure 8-3. The Purchasing Chessboard: 64 Detailed Methods

In our view, SRM and the Purchasing Chessboard cover very different areas and have quite different objectives. While SRM is about leveraging a company’s size and driving desired supplier behavior, the Purchasing Chessboard is about developing the right category strategies. As outlined in the previous paragraph, success is measured by very different key performance indicators as well. The success of SRM is measured by competitive advantage achieved and defined very broadly. The success of the application of the Purchasing Chessboard is predominantly measured by cost reductions achieved with suppliers. At a secondary level, the Purchasing Chessboard also aims at creating value with suppliers, but this value creation is always strictly linked to a given category.

Let’s now examine if there is a correlation between the SRM framework and the Purchasing Chessboard.

Suppliers in Harvest, Improve, and Mitigate have low strategic potential with categories that can fall almost anywhere on the Purchasing Chessboard. The only area on the chessboard that will be mostly untapped by categories provided by these suppliers is the upper-right quadrant representing the “Seek joint advantage with suppliers” basic strategy. The reason for this is that high supply power and high demand power in the upper-right-hand side quadrant of the chessboard would translate into medium or even high strategic potential.

Suppliers that fall into Influence, Sustain, Develop, Integrate, Invest, and Bail Out in the SRM framework have medium or high strategic potential with categories that can fall almost anywhere on the Purchasing Chessboard. The only other area of the purchasing that will be mostly untapped by categories provided by these suppliers is the lower-left-hand-side quadrant, representing the “Manage spend” basic strategy. The reason for this is that low supply power and low demand power in this quadrant translate into low strategic potential.

For suppliers that fall into Bail Out, the category or product that causes the bailout will almost certainly sit in the upper half of the chessboard. This category or product will involve a novel technology that this supplier has been one of the very few players on the planet to master. The supplier therefore enjoys high supply power for this product.

With these considerations in mind, we can summarize that at a high level, the SRM framework and the Purchasing Chessboard are mutually independent tools. The only exception is the Strategic Potential axis in the SRM framework, which is weakly correlated with the Purchasing Chessboard in the following ways:

· Low Strategic Potential in the SRM framework excludes the combination of high supply power and high demand power in the Purchasing Chessboard.

· Medium and high Strategic Potential in the SRM framework exclude the combination of low supply power and low demand power in the Purchasing Chessboard.

How to Get Started

The SRM framework in this book is structured, repeatable, and scalable. Putting it to work is more of a change-management effort than an intellectual challenge. In our experience, suppliers appreciate the introduction of the framework, but internal resistance should be expected.

![]() Note Expect resistance to the SRM framework internally. As always, it’s easier to maintain the status quo. To attain meaningful change, top executives must endorse the initiative and see the change through.

Note Expect resistance to the SRM framework internally. As always, it’s easier to maintain the status quo. To attain meaningful change, top executives must endorse the initiative and see the change through.

Resistance will first build against one of the key objectives of SRM—leveraging the company’s size. Realizing this objective will require coordination across functions, lines of business, and hierarchy levels. Out of routine, for all involved players, it will be easier to do what they have done in the past and go out to engage with the supplier without coordinating upfront. Change here will not come without strong endorsement from the very top of the organization. We recommend using a very simple line to convince the CEO to lend his or her endorsement. The best argument is to equate suppliers with customers. Everyone usually understands readily that internal alignment and consistent messages are needed when dealing with customers. The use of key account management and CRM (Customer Relationship Management) is well-established on the “sell” side. The same disciplines are consequently needed on the “buy side,” namely, SRM.

Resistance will also be strong when the initial segmentation of suppliers takes place. Too many owners of supplier relationships will want to see “their” suppliers in the top-right-hand corner of the SRM framework. We cautioned against the inflationary use of the term partner in the introduction of this book. And we agree that it is a nicer job to inform a supplier that it resides in Integrate than to explain why Sustain or Harvest are more appropriate. The following steps have worked well for avoiding resistance to the results of the segmentation:

· Compare team members’ segmentation to their annual performance evaluations. No organization would tolerate having all employees in the top category. This would make the evaluation process meaningless and demotivate top performers. The same is true in SRM.

· Refrain from overcommunicating the segmentation results. Suppliers with low strategic potential—that is, those in Harvest, Improve, and Mitigate—do not need to be informed about the SRM framework and their positioning at all. We are talking about 90 percent of suppliers here and with this measure, the workload associated with getting SRM going is reduced as well. There is also no need for keeping SRM a secret, though, and all interested suppliers will eventually learn about it. But for those 90 percent, the time when they actively ask is an early-enough point at which to inform them.

· Work with primary and secondary interaction models. As previously explained, the primary interaction model indicates where the supplier really sits today, but the secondary interaction model can be used to deliver a more aspirational message.

The most resistance can be expected when a supplier is entering the Integrate interaction model. Let’s discuss this by looking at a case example.

Case Example

A major carmaker with several brands had a colorful relationship history with its largest supplier of interior systems. Interior systems encompassed everything that the passengers in the car could see, touch, smell, and hear. Many executives at the carmaker agreed that the supplier had played a crucial role in making several car lines very successful in the market, but there had also been ups and downs in the relationship.

What counted for the carmaker was to achieve a high market share at a competitive cost. Since the interior system accounted for a significant portion of the externally sourced expenditure of a car, the supplier was the key focus of several past cost-reduction initiatives. The supplier got sourced many times and now claimed to be in the red with several product lines. The carmaker did not believe this and substantial management resources were dedicated on both sides to haggle over cost.

From the perspective of the supplier, it was quite hard to do business with the carmaker. It got conflicting messages when talking to Procurement, Engineering, and Product Management. Also, the different brands of the carmaker were not aligned with regard to the supplier. The supplier could be in favor with one brand while falling out of favor with another. At the top, the CEOs of the two companies entertained a quite-active communication channel but did not align internally, which led to additional confusion, mostly to the disadvantage of the supplier.

In summary, all these factors had pushed the supplier into a reactive mindset. The supplier had sat back and waited for the carmaker to give instructions, based on which the supplier would execute. Whenever there had been a disagreement, the supplier would respond, “But you told me to do so.”

At a certain point in time, key players at the carmaker recognized that there was a big missed opportunity with this supplier. With sluggish global car markets and increased competition from new competitors, there was a realization that the future of the automotive industry would be determined by a competition of ecosystems. They then defined five key success factors for the collaboration with the supplier:

1. Bringing the supplier in for the concept phase already as a partner with equal rights

2. Granting the supplier exclusivity in certain product market segments

3. Sharing responsibility for volume, price, and margin with the supplier

4. Making engineering, marketing, and procurement decisions jointly with the supplier

5. Clearly aligning competencies to avoid duplications and overlaps

First and foremost, the supplier needed to be elevated from its reactive mindset. With the supplier just executing the instructions and specifications of the carmaker, major opportunities were lost. Not only did the carmaker not leverage the vast experience and insight of the supplier into its recent developments in interior systems, but the specifications it developed often were difficult and expensive to make. Bringing the supplier in for the concept phase already as a partner with equal rights led to a true paradigm shift. Resident engineers and product planners from the supplier joined the carmaker’s cross-functional product-development teams. The supplier’s experts completely changed the way the carmaker was looking at interior systems. For the first time, the carmaker’s key source of inspiration was not the models that competitors displayed at auto shows but the input of the supplier, which involved very concrete and feasible ideas on how the interior system of the future should really look.

For the supplier to open up so radically to the carmaker, it needed assurances that its breakthrough ideas would not just be taken from it and then realized with one of its competitors. Therefore, the carmaker granted the supplier exclusivity for those car lines for which the supplier had injected its breakthrough ideas. There also was a very explicit understanding that this exclusivity had no limits. Provided that the carmaker’s volume and profitability targets for the car lines in the scope of the agreement were met, the scope would be expanded to additional car lines. In the best case, the supplier would eventually own the interior systems of all car lines. Under that agreement, it was also made clear that car lines within the scope would be out of reach for the supplier’s competitors. Since it had so heavily influenced the overall design of the interior system, a competitive quote that would just cover making and assembling the parts would be considered irrelevant.

As an assurance for the carmaker that the supplier would not just lean back and relax, a set of strict incentives and penalties were agreed upon. In fact, the supplier shared the entrepreneurial risk for the car lines in scope. It took some time for the supplier to agree to this principle, but once comprehensive marketing research confirmed that the interior system was indeed a key criterion for the end customers’ buying decision, the supplier agreed. In the incentive and penalty scheme, volume, price, and margin targets for the car lines were established. For every unit of positive deviation from the target, the supplier would receive a bonus payment; for every unit of negative deviation from the target, the supplier would have to pay a penalty.

In order to agree to the incentive-and-penalty scheme, the supplier requested that it have a say in all operations, marketing, and sales decisions concerning the car lines in scope. After some hesitation, the carmaker understood that there was no way to avoid doing this and opened up to the supplier. Functional task forces, staffed from both the carmaker and the supplier, were established to work on day-to-day decision making. A joint executive steering committee would now provide strategic guidance to these task forces.

Under the cost pressures of a sluggish market, both parties then looked into synergy potentials. This initiative was driven by the carmaker, which first revisited its core competencies in interior systems. Everything that was not considered noncore was by definition to be performed by the supplier. This exercise yielded head-count savings across several functions with by far the biggest chunk in engineering.

Creating Momentum for SRM

Implementing any of the five key success factors will meet a substantial level of internal resistance in any company. Bringing the supplier in as a partner with equal rights at the concept stage will frighten engineering and product-marketing people. Granting the supplier exclusivity for certain product market segments will raise concerns about losing leverage and competitiveness. Sharing responsibility for fundamental operations, sales, and marketing with a supplier will be a stretch for all involved parties. And aligning core competencies, with the resulting reduction in head counts, will clearly not be welcomed by those affected.

So, how can the required momentum to introduce SRM be created? As usual, it is the right combination of focus, quick wins, and baby steps. Focusing on those suppliers that will make a difference is the first ingredient for success. Suppliers in Influence, Integrate, and Invest are those that really warrant the attention of scarce management resources. Even in companies that have thousands of suppliers, not more than a couple of handfuls of suppliers will fall into those three interaction models. Therefore, focusing on those suppliers will ensure that resources for SRM are not spread too thin.

Delivering a couple of quick wins is paramount. If SRM enables a new technology from an Influence supplier to be used with a customer, a hot-selling product to be developed with an Integrate supplier, and a tangible performance breakthrough to be achieved with an Invest supplier, many stakeholders will want to join the bandwagon. Therefore, a lot of thought should be dedicated to what these quick wins can be even before rolling out SRM.

Finally, taking baby steps in a controlled, manageable environment is better than drowning in complexity. In the automotive interior systems example just looked at, the Integrate relationship with the supplier was initially limited to two car lines. Those car lines had a team of executives that was generally friendly and supportive to the SRM initiative. They provided an environment in which quick wins could flourish and attempts to derail the idea were deemed to be unlikely.

How to Make SRM Sustainable

In order to be sustainable, SRM must evolve from the initiative status to being embedded in the company’s culture, organization, and DNA. Realistically, this will be a multiyear process with numerous setbacks and disappointments. Therefore, it is important for the company’s leadership team to keep the eye on the prize. If done right, SRM will become a competitive advantage that cannot be substituted by old-school, one-size-fits-all supplier squeezing.

Heartland’s TrueSRM In The News

Let’s return to the story at Heartland. We are now two years on from the events of the month of mayhem that are described in Chapter 3. Thomas, Laura, and the team have successfully put SRM in place. As described in Chapter 4, the procurement function has been transformed to focus on high-value activities and supplier relationships. Heartland has systematically implemented the different interaction models across its supply base. As shown in Chapters 5, 6, and 7, the company has gained considerable benefit in the process.

Heartland’s success has started to attract considerable interest in the marketplace. This has come about in several ways. First, the restructuring of the procurement function became very well-known externally. Heartland’s hiring of nontraditional MBA graduates attracted considerable attention. The subsequent creation of the supplier development function also became very well-known and was seen in some quarters as unusual for the food industry. However, the reporting of these developments did not go beyond the procurement press and specialist supply-management blogs.

Another development also attracted considerable attention. This was the decision to replace the existing creative agency, Delta Creative. Of course, many companies replace suppliers. However, decisions to replace creative agencies are rarely taken lightly. This particular relationship was also of such long standing that it really did cause quite a stir. It was reported heavily in both the procurement press and throughout the marketing world.

So far, these developments did not attract attention in the general business world, nor in the mainstream business press. This all changed with the three developments that are outlined in Chapter 7. First, the appearance of the Heartland energy drink brand in orbit and the subsequent announcement of the relationship with Product Maniacs caused excitement well beyond the marketing world. Heartland had always been seen as a very conservative business. Admittedly, this was perhaps a slightly unfair estimation. The very way that Thomas had been recruited as CPO from a chance meeting with the then CEO on a plane trip is just one example that exposes the lie in this. Nevertheless, this was the way that the company was seen. The relationship with Product Maniacs really was something else. Close observers of Heartland were now starting to wonder whether something more systematic was taking place to change things.

The second was the launch of the joint organic food range in conjunction with the high-end grocery EATing. Previously, EATing had eschewed such tie-ups with suppliers. Despite being a high-end food business, it had treated its private-label suppliers as pure subcontractors. The relationship with Heartland really was something else. This was picked up by the mainstream business press in a very significant way.

The third development that really made observers feel that something systematic was taking place was the co-commercialization of the color-changing film with Caledonian. This innovation went viral in the news media and caused a 10 percent increase in Heartland’s stock price.

The world was now sitting up and taking notice. Perceptive observers were now starting to make the link that the “something” that was going on was related to how Heartland was working with external suppliers. Foremost among these observers was Elisabeth Huttich, a top writer for one of the leading German-language business journals that was also syndicated in the English speaking world. Thomas’s role as CEO of such a traditionally Midwestern business as Heartland had always been a great human-interest story for her readers. She had interviewed Thomas when he became CEO at Heartland. Elisabeth was probably the first external observer to deduce that Heartland was behaving “differently” toward its external supply base. She reached out to Thomas and requested an interview for an article she decided to write called “Has Heartland Found the Secret Sauce for Working with Suppliers?”

So, one chilly February morning, in Fort Wayne, Elisabeth was ushered into Thomas’s office, where Thomas and Laura were there waiting for her. So was Emma Jenkins, the head of investor relations. She wanted to chaperone both Thomas and Laura to help them ensure that they were mindful of corporate codes of conduct with respect to price sensitive information.

Elisabeth and Thomas greeted each other with the traditional continental kiss on each cheek. Elisabeth had not previously met Laura and Emma. After introductions and some small talk, Elisabeth got down to business. “As I e-mailed you about, Thomas, I am really interested in understanding exactly what Heartland is doing in supplier relationship management. The success you are all having is amazing,” she said. “Everyone else seems to struggle. What are you all doing?”

Thomas looked at Laura. “Laura, you have orchestrated things. Why don’t you tell Elisabeth what we have been doing?” Then, he paused and looked at Elisabeth. “Laura can’t tell you everything though. We don’t want the whole world copying us in everything we do. We need to keep some secrets,” he said with a smile.

Laura then started to explain the development of the interaction models to Elisabeth, the use of the framework to segment the supply base, and then some of the actual cases of what Heartland had done with specific suppliers. Elisabeth was clearly fascinated by Laura’s storytelling. After an hour or so, they paused as coffee was brought in.

Elisabeth sat back and asked: “So, Laura, was it just about having the framework? Lots of companies have supplier segmentation frameworks, but they have not achieved the type of success you have achieved. Was there more to it?”

“Yes,” answered Laura. “Having the right framework that focuses on current performance and strategic value matters. But the really key thing is that we have made it a living-and-breathing organism that is intrinsic to how we run the business. It is far more pervasive than a pure procurement approach.”

“How so?”

“Well. First of all, we never lose sight of what SRM is about. You know many companies think it is about process, score cards, or is somehow an adjunct to category sourcing. ”

“You do hear that,” Elisabeth agreed.

“Well, it’s not. It is about how you drive desired supplier behaviors. Process, score cards, and governance forums are only a means to an end. Too many organizations that we talk to see SRM in these exclusive terms. These things matter, but they must be implemented in context and be appropriate to the supplier’s interaction model and the things you are seeking to achieve.”

Elisabeth nodded in agreement.

“Second,” Laura continued, “we do not confuse SRM with category sourcing. We use the Purchasing Chessboard to determine our strategies in category sourcing. It is all about how we choose to buy specific goods and services that happen to have the same supply markets. That is not the same thing as driving desired supplier behavior. Not at all.”

Laura paused. “I see,” offered Elisabeth. She thought for a couple of seconds. “Are they really so different though? Threatening to launch a bidding contest with a supplier surely has some impact on behavior? I am not sure I really agree with your point.”

“Let me explain it more carefully,” said Laura. “It’s a bit subtle. Sure, category sourcing and SRM need to be complementary. The sourcing levers a company chooses to use have a big impact on supplier behavior. Your example of a tender is perfectly valid. Suppose we have an Integrate supplier. We have a very close relationship with the company that we gain competitive advantage from. We then decide to threaten a tender or create a contractual dispute that we bring the lawyers in over. It’s bound to affect the relationship if we do these things. And, we have to think about that when we choose our sourcing levers. This does not mean we won’t get aggressive if we have to, by the way, but we think about the wider impacts if we do need to. The key point remains, though, that category sourcing is about how I choose to buy goods and services and SRM is about how I drive desired supplier behavior.”

“I see that,” said Elisabeth.

“Third, we have made a corporate decision that SRM is the right thing to do. The success of SRM at Heartland has therefore never been measured in cost terms. Our focus has been much more holistic—on innovation, risk reduction, and revenue enhancement. We have resisted the urge to micromeasure the impact of our activities.”

“That must have been quite hard to pull off,” commented Elisabeth. “The need for business cases is a refrain that one constantly hears.”

“We have stuck to our approach. Thomas strongly drove, and still does drive, the vision. He has given us top cover to focus on this. It’s a bit like sustainability—you are, in my view, either committed to it or not. To subject every aspect of it to a micro-financial-business case is to miss the point and will ultimately be self-defeating. We have very much taken that approach to SRM.”

“That is very inspiring,” said Elisabeth.

“The fourth point is consistent with our strategic mindset for SRM. We have driven our approach to supplier interactions top-down from a corporation-wide perspective. Many people make the mistake of driving segmentation entirely via categories. With this approach, different parts of the business, or worse still, procurement category managers, nominate ‘strategic suppliers.’ The problem is that everyone wants to feel they have some strategic suppliers. So, you get suppliers that, for our business, could never lead to real innovation or competitive advantage being nominated as strategic. I have heard of facilities’ suppliers being labeled as ‘strategic’ because they are big. For us, they are Harvest, and certainly not Integrate.”

“I can see the problem,” said Elisabeth.

“It stems very often from failing to distinguish between category sourcing and SRM, as we already discussed. Instead, we drive our resource allocation and the effort that we devote to particular suppliers entirely top-down from our framework. So, we devote most attention to the Critical Cluster for positive reasons and to the Problem Children for negative ones. We put far less attention into the Ordinaries.”

“Is it really so special to prioritize in this way?”

“Most organizations prioritize in a much less top-down way,” Laura explained. “They tend to drive resource allocation and effort from categories and size of spending rather than from a true perspective of performance and value. The resource prioritization is not just about how we allocate procurement people. We have found that the biggest benefit is how we allocate management time and decision making time. It’s a mindset thing. For example, we found that one of the suppliers we now rate as Harvest had an account team of 12 people and they were involved in an executive-level meeting every couple of days. They are a good-performing supplier, but this was completely inappropriate. On the other hand, we now consciously devote far-more executive-management time to organizations such as Product Maniacs now. We have completely changed the way we think about the priority we give to different supplier relationships.”

Elisabeth sensed that Laura was really very excited by what had been done. “It’s a really inspiring story,” she said. “I am very impressed. Is there anything else you would like to highlight? ”

“Well,” said Laura. “The fifth point is that we treat this as a dynamic thing. That has enabled us to focus on giving suppliers consistent, aligned, and aspirational messages. That is something we are still learning, I would say. It only comes with experience. Suppliers can change position. Performance can ebb and flow.”

“Can you explain?”

“Well, let me start with performance. We do not want suppliers becoming complacent. To avoid this, we took a decision in the past year to force-rank every supplier in performance from an overall Heartland perspective, irrespective of category.”

“That must have been quite a challenge.”

“Indeed,” said Laura, “it was. But, we stuck to it. It forced some challenging internal conversations. Initially, we got too hooked up on small differences between suppliers that were all broadly in the middle of the bell curve anyway. That was not so helpful. Then we realized it would be much more useful to focus on understanding who the bottom 10 percent of performers were and who the top performers were. For the bottom performers, it has forced tough internal conversations on whether we should replace them. It has also meant we have been giving some of the suppliers very aspirational messages to improve. This has been particularly the case where a supplier is performing poorly but is potentially quite valuable for us. In such a case, replacing them is far less of an option. There are already encouraging signs of improvement among some of them.”

Elisabeth nodded in understanding. Laura went on. “We are just about ready now to refresh the ranking work. We learned a lot the first time around. It will be more focused this time and we will be even sharper on delivering the right messages.”

“What about strategic potential?” asked Elisabeth. “Is that dynamic too?”

“Much less so,” Laura said. “It’s much harder for strategic potential to change over time, because it is governed by the specifics of a supplier’s business. But it can occasionally change as well, of course.”

“How so?”

“Well, there is an example of an Influence supplier that we are reclassifying as Integrate. It is Caledonian Packaging, headquartered in Edinburgh. The level of cooperation we are achieving and the access we are now getting to its future product pipeline is really quite breathtaking. We are coming up with some great stuff together. So, that is—”

Emma, who had been largely silent up to now, interrupted. “Could you treat that as off the record, Elisabeth? I would prefer you did not publish it.”

“I understand,” said Elisabeth. “You have all been very open. I respect your need for confidentiality.”

Laura blushed slightly. “Yes, thank you. We are not quite ready to communicate this with Caledonian yet, either. We have been hinting at the reclassification for a while.”

“Yes,” said Thomas. “My good friend Calum Drummond is salivating to get that designation. I want to make him sweat just a little longer before we finalize it!” They all smiled and Laura stopped blushing.

“The fact that such a respected CEO pays such attention to how you classify his business really brings home to me how powerful this is,” said Elisabeth. She noticed the time and that the two hours scheduled for the session were nearly over. It felt like a natural endpoint anyway. “On that note, thank you very much for such an interesting morning.”

She exchanged her goodbyes and left for the airport. That afternoon, Elisabeth boarded her flight back to Munich. As the dinner service started, she reviewed her notes and captured five key success factors for SRM that she would use in her article.

Key Factors

Let’s look at the Five Key Success Factors that Elisabeth captured:

1. Never lose sight that SRM is about driving desired supplier behavior based on the appropriate interaction model. Process, governance, and score cards are purely means to support that end.

2. SRM is complementary with but distinct from category sourcing. Category sourcing is about how you buy things, not about how you drive supplier behavior.

3. Make a strategic decision to implement SRM because it is the right thing to do and will deliver competitive advantage. Resist the temptation to micromeasure benefits.

4. Drive the segmentation of suppliers and prioritization of resources across the organization. Resist the urge to segment category by category or to allow category leaders to “vote” on supplier classification.

5. Treat the interaction models as dynamic: Rank suppliers, make tough decisions, and give aspirational messages. Do not allow suppliers or yourself to become complacent with the status quo.

Bring SRM to Life

In this chapter, we talked about how to bring SRM to life. To do this, you need to treat the interaction models as dynamic by recognizing that changes occur over time. Use the framework to drive desirable change by giving suppliers consistent and aspirational messages. Be prepared to make the difficult decisions that are needed when less desirable changes happen. Make sure that the governance structure is aligned to the interaction models, that relationship owners are in place, and that communication to suppliers is consistent. By these means, you will help suppliers to help you in the most effective way.

We then went on to discuss the very clear distinction between SRM and category management. The former is about leveraging a company’s size and driving desired supplier behavior. The latter is about developing and executing the right strategies for sourcing goods and services—for which the standard tool is the Purchasing Chessboard.

Finally, we discussed how to get started, create momentum, and, importantly, make SRM sustainable. We illustrated this by catching up with our friends at Heartland as they looked back and discussed what they have done to put SRM to work.

The key element that we have not discussed so far is the role of IT in SRM. In the next chapter, we turn our attention to this topic.

1For more information about the Purchasing Chessboard, please refer to www.purchasingchessboard.com.