Supplier Relationship Management: How to Maximize Vendor Value and Opportunity (2014)

Chapter 7. The “Critical Cluster”

Driving Behavior to Get Results

Our tour of the different clusters is completed with the “Critical Cluster.” We finish here because this is the area where the most important suppliers will be located. These are suppliers that can contribute to competitive advantage and where the relationship needs special nurturing. It is from these suppliers that you will get the most innovation and risk mitigation.

The secret sauce to making this relationship model work is to establish trust with these suppliers. Failure to create the necessary level of trust is probably the number one reason so few companies create such deep relationships with these suppliers. Free markets and competition encourage companies to be secretive and protect their competitive advantage while it lasts. Many are afraid they will lose it if they get too comfortable with their suppliers, which in many cases also cater to the company’s biggest competitors. But establishing deep trust can work, and we are strong believers that every company that wants to can reap the benefits of a close relationship with the right suppliers.

Think of one of the world’s most secretive consumer-electronics companies, notorious for keeping its newest products secret even to most of its own employees. Yet part of its secret sauce is working very closely with key partners that help develop, test, and manufacture most of its products. The relationship is built on strong mutual dependence and deep trust going beyond cultural barriers, which has vaulted both companies to the top levels in their industry.

Most companies won’t have that level of trust with suppliers when starting with SRM. The way forward is to focus on the fundamentals of the interaction model first, and then develop trust through time as the relationship deepens and evolves. Using the concrete actions of collaboration as stepping stones serves to build that trust. Lastly, being transparent with the supplier in applying the interaction model is a way to engender trust with it.

Let’s look at each of the three types of suppliers in the Critical Cluster in depth.

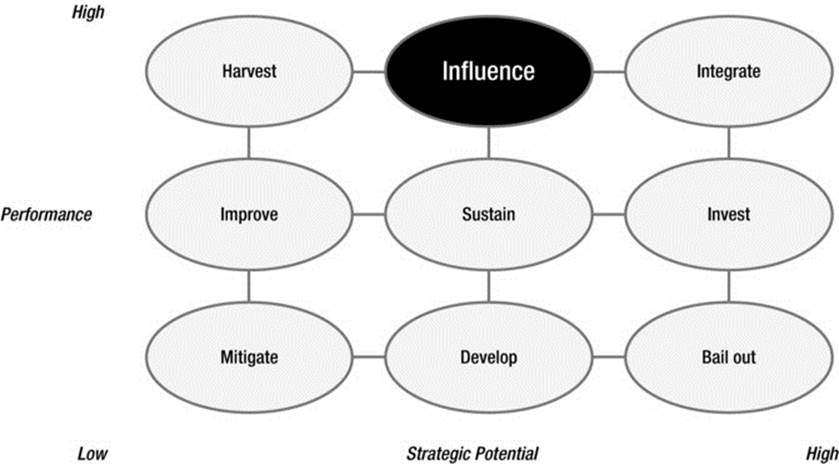

Characteristics of Influence Suppliers

Very few suppliers will fit the Influence model (Figure 7-1). To do so, they would have to perform very well in all regards. You could say that those in this model deliver nearly perfect products or services. What sets them apart is that they offer the potential for innovation when you work with them jointly to develop new products or services. This factor shapes your relationship with them.

Figure 7-1. Influence suppliers on the strategy/performance axes

Compared to Integrate suppliers, companies cannot build lasting competitive advantage with Influence suppliers. This is because they do not offer the full long-term and all-embracing partnership that is required to steal a march on your competitors over the long term. These suppliers often dominate an industry, as they are among the critical few that a company and its competitors rely on. They supply key technologies or services that define the industry’s standard and their share of wallet is likely to be very high. To provide such a high level of innovation, they often invest heavily in development or capital equipment cost. As a result, they will often favor scale over exclusivity in order to amortize the up-front investments. In turn, they do not favor any one customer, and, in the case of monopolistic suppliers, are required by law not to do so. At times, you may be able to achieve limited exclusivity on specific innovations as a launch customer in return for assisting with the upfront development. However, over time, the Influence supplier will certainly seek to make the innovation available more widely. This is a reality that you need to recognize.

So, you get cutting-edge service and innovative products. The downside, of course, is that it is nearly impossible to outpace your competition forever when you work with these suppliers. What’s more, mismanage this relationship, and you could alienate these suppliers enough that you fall behind the competitors that are better at handling their relationship with the same supplier.

What Kind of Behavior to Drive

The preferred behavior from an Influence supplier is to be able to affect its innovation roadmaps and be the first to the market with new technology. You will, at least, want to get some level of preferential treatment as well. The essential ingredient to the relationship is building trust and an incentive structure that will motivate the supplier to open up. The supplier has to see the type of competencies you bring to the table and the benefit in working with you in particular. You need to put yourself in its shoes to truly understand what drives it. As a highly innovative technology company, it may seek a company with a strong sales channel to quickly position its products and drive fast growth. Or it may be after specific market segments in which it is not yet established or that it sees as being of strategic importance. Then again, it may just need a sufficient initial order to jump over the internal hurdle to get the final “go” to develop a new product or service.

An Influence supplier may aspire to become an Integrate supplier with your organization, but that will only happen in very few selected cases, as it would mean deprioritizing or even ignoring other customers. This may happen in the case of a nascent technological innovation that presents a high, risky bet and where a powerful ecosystem of specific customers and buyers provides the right mix of competencies to make it work. The company is hoping to get as much out of the relationship as you are. Once the technology becomes more mature, the relationship might drift back to Influence, but this may take several years or product and service generations to come.

On the other hand, the supplier may fall short in terms of future innovations and—even while maintaining the same flawless performance levels—might move back to being a Harvest supplier. This will happen, for instance, when there is a jump in the technology curve and the supplier has missed the innovation window either as leader or follower.

How to Work with Influence Suppliers

As with most relationships in life, good timing and regular communication are critical for capitalizing on opportunities with Influence suppliers. You want to set the expectation up-front that it is necessary to have access to their product, technology, process, and innovation roadmaps. Evaluate the supplier for opportunities that you can tap into or even areas that could provide limited exclusivity. Request ongoing feedback on how your company’s actions and plans dovetail with its own for mutual advantage, and then negotiate competitive pricing accordingly. And don’t be shy and stop here; rather, go further to also align on strategy and dedicate resources to generate a sustained competitive advantage.

Influence relationships can consume a substantial amount of resources, so you need to make the investment pay off by encouraging confidence in each other’s plans. In case of interesting new product technologies, you might want to become a launch customer to gain first-mover advantage and to get preferential treatment over the lifetime of the product.

![]() Note Influence relationships can be time-consuming, so make the investment pay off. Ask to become a launch customer for an innovation, for example. That can give you that coveted “first mover” advantage, as well as goodwill you can capitalize upon later.

Note Influence relationships can be time-consuming, so make the investment pay off. Ask to become a launch customer for an innovation, for example. That can give you that coveted “first mover” advantage, as well as goodwill you can capitalize upon later.

As a launch customer, you will be first to recognize the potential future strategic value of the new product or service, and must often be willing to write a check several months if not years in advance before actually seeing the result. But keep in mind that Influence suppliers are not just looking for resources—if that were the only thing they were interested in, they could go elsewhere. They are mostly looking for a sales channel to find first users of their innovation right after the product launch. Becoming a launch customer enables exactly that: It provides a convincing sales channel and commitment to buy sufficient ramp-up volume. In return, the supplier will get preferential treatment and even a say in the product- or service-development process. This can be valuable; the company may suggest certain features that would otherwise not have been considered by your development team. In many cases, there will be an exclusive relationship for a certain amount of time after the product launch. It may not last long, though. To drive improvements and stay competitive in the market, the supplier will go after scale and start offering the same product or service to other customers. As a launch customer, you may nevertheless still receive special treatment in terms of higher price discounts, better product or service support, and committer capacity, something that can be especially critical in times of supply disruptions.

Governance

These relationships are based on mutual trust, so you want to make sure the supplier understands the importance of the relationship to you. Nominate a sponsor for the relationship on both sides, someone with sufficient political weight to drive the alignment of priorities for new product or service development. Mutual teams could be built to drive development of future products. The supplier may even send dedicated people to join your development teams and allow for real-time feedback loops.

Typically, you should expect a series of regular formal executive reviews, at least quarterly, that focus on identifying future opportunities and reviewing progress in collaborative innovation efforts. In addition, plan to hold a series of informal meetings to strengthen the relationship at all levels and across different stakeholder groups.

Case Example #1

Let’s look at an example for Influence from the commercial aircraft industry, which is an extremely complex industry. It has high barriers to entry and it is capital intensive, with companies realizing profits only after a long time. With only a few manufacturers of aircraft—even just two in the long-distance aircraft market—the airlines will never be able to get exclusive deals from any of them. So there is a strong incentive on the airline side to gain access to new aircraft development as soon as possible and get the starting advantage over other airlines.

In the late 1980s, the aircraft maker Airbus started to think of developing a new ultra high-capacity airliner to break the dominance of Boeing’s 747 as the only true high-capacity, long-distance aircraft. Developing new technologies and designing aircraft is a long-term process with significant financial risk; the development costs of designing a new airplane are in the billions. Singapore Airlines recognized the opportunity by building a strong relationship with Airbus. Both sides had high win-win expectations for their cooperation. The airline wanted first-mover advantage as the launch customer, but it had a primary interest in influencing the development process, specifically the design of the passenger cabin. The aircraft producer was given security through a committed initial order from one of the leading global airlines with a convincing marketing arm that would quickly bring other customers on board.

Singapore Airlines capitalized on the possibility of influencing the design process of the cabin by redefining the flying experience. The new first class is not even called that anymore—the company describes it as “beyond first class.” The luxurious suites are targeted at passengers who do not want to compromise on either sleeping or the seating and working experience while in air. Each “suite” has a full-size mattress, sliding doors, and pull-down windows. It more resembles an old, classy train cabin than an airplane seat, and it sets a new standard for luxury in commercial aircraft. The flight attendants actually walk between walls, not seats. If you want to work on your computer, you can connect it to the large screen hanging on the wall of the suite. If you want to dine with another passenger, you can do that as well. There is even a suite with a double bed that the airline coined as “honeymooners’ suite.” This clearly propelled the airline to the top as the trendsetter for luxury air travel. The airline also cares for its staff and has further improved the area flight attendants work in. Several additional comfort features have been implemented for both pilots and the crew.

Singapore Airlines had great success as the launch customer for the new jumbo jet. It significantly expanded its brand value, customer base, and new services. In less than one-and-a-half years, the one-millionth passenger flew with Singapore Airlines on the new A380 aircraft. A big marketing effort, followed by extensive media coverage, turned the airline into the best-known airline carrier. Especially successful was a charity auction on eBay, in which passengers bought seats paying between $560 and $100,380 for the first-scheduled flight of the aircraft. That turned into a huge marketing success. To commemorate the inaugural flight, passengers received a personalized certificate showing they were part of the first historic flight. The airline also profited from the early stage of cooperation by being able to develop a new customer experience with the newly defined business-suite class influencing the aircraft’s interior design.

Airbus’s advantages from the early-stage cooperation turned into a big success as well, as they not only heard the voice of the customer through the entire product development process but also profited from free media coverage. And even more important, the buying commitment from one of the largest and most admired airlines positively influenced buying decisions from other airlines.

Case Example #2

The same kind of close working relationship paid off for the transportation authority of London, a city which already had a highly modern fleet of off-the-shelf buses in operation. In this case, it wanted a new bus that was especially tailored to London’s operating conditions. It also wanted the new bus to become as iconic on the city’s streets as the classic open-platform Routemaster design of the 1950s had been. In short, London desired a bus that would be an emblem for the city. In 2010, it chose the outline design via a public competition and selected Wrightbus for the manufacture and detailed design. The detailed styling was then produced through close collaboration with Heatherwick Studio.

The suppliers created a unique vehicle that meets the specific needs of London’s ridership with full wheelchair and pram accessibility, a hybrid electric- and diesel-power engine, and an aluminum frame, making it one of the most environmentally friendly buses in the world. The iconic featureof a rear open platform enabling hop-on, hop-off operation when a conductor is present was preserved. Building on the success of its namesake predecessor, the new Routemaster features asymmetric glass swoops as its signature “futuristic” styling feature.

Inspired by the classic Routemaster, the transportation authority and bus manufacturer developed the first bus in more than 50 years to be designed specifically for London’s streets. This joint supplier relationship successfully introduced this cutting-edge vehicle on the city’s streets and produced the largest order for hybrid buses in Europe. The transportation authority has had significant influence on the bus manufacturer’s product roadmap and the design of the bus. While the bus is quite specific to London, it will be available for the broader customer base interested in purchase of double-decker city buses.

Collaboration Pays Off for Heartland

Laura was musing over the missed opportunity that Marshfield had represented as she walked into the office at Fort Wayne one morning. There was a spring in her step, though. She was wondering whether today would represent redemption for Heartland Consolidated Industries and a tangible outcome from TrueSRM that would really be “something big.” For today was the culmination of many months of really focused work between a cross-functional Heartland team and Caledonian Packaging, a packaging-industry competitor of Marshfield. It was the day that both companies would make a formal announcement of a major new innovation into the market. The innovation was being made by Caledonian. Heartland was committing resources and funds. In return for the resources and funds, Heartland was made the launch customer. Analysts, customers, and press representatives had been invited. The innovation was expected to have a major impact on both Heartland’s and Caledonian’s respective revenue and stock prices. The presentation really needed to go well. The atmosphere in Fort Wayne was electric. The spring in Laura’s step was tinged with trepidation.

The story had started six months before. Caledonian was a long-term supplier to Heartland. It had reaped much of the benefit from the long-term decline in Marshfield serving as a Heartland supplier following the great “ripping film” debacle. Yet there was a sense that Caledonian had grown a little complacent at Heartland. Nobody could remember the last great innovation that Caledonian had introduced. It was not clear to anyone, in fact, that they “did” innovation at all. However, they were seen as safe, their film and other materials worked in Heartland’s machines, and no one was likely to get fired for using them. Heartland was also not sure that it even needed packaging innovation, especially in the post–ripping film era.

As we have seen, this apparent complacency on both sides was dramatically shaken by the “Tastes Fresh Longer” innovation. Both Heartland and Caledonian were embarrassed. The initial reaction was, as might be expected, one of mutual recrimination. Both Laura and Thomas had attended a meeting to which they had urgently summoned Calum Drummond, the Caledonian CEO, and senior members of his team. This had been a very difficult meeting. The Heartland executives started out by berating the Caledonian people for being complacent and not bringing anything to the table. At first, Calum had stayed silent, while his colleagues politely listened to Heartland and showed contrition.

However, the meeting turned ugly when Heartland’s CFO, Garner, intervened and commented, “You know, I really wonder whether Caledonian should be one of our suppliers going forward.”

Calum was a feisty Scotsman. There was no way he was going to tolerate any more one-sided abuse. “A customer gets the behavior it deserves,” he contested. “You have wanted safety and security for the past three years. Everything you have told us has to do with ‘Please make sure there are no more ripping film sagas.’ We have done what you asked. You have shown no interest in any innovation that we have shown you. You reject everything that is new. The ‘no more ripping films’ instruction is engraved on our hearts. Now, when you are caught out, you have the gall to blame us. I am shocked at what I am hearing today. Do you want to fix things or just sit here kicking my team? I have had enough . . . .”

Calum motioned to leave.

Thomas, who had been silent, raised his hand to speak. “Calum, let’s fix things. I hear you. I think we have all got a little emotional today. Let’s have a short break to stretch our legs.” He summoned Calum and the two of them stepped out of the room together and walked toward Thomas’s office.

“Thank you for pushing back, Calum,” said Thomas. “That is always hard for a supplier to do. My team were maybe a little out of order but you can appreciate the emotion this has aroused.”

“I do,” said Calum.

They entered Thomas’s office. “So tell me,” inquired Thomas, “What are these innovations we keep rejecting? I am intrigued.”

Calum had a seat. “Well,” he said. “There are many examples. But the one we are really proud of is that we came up with an idea for a film that changes color. It changes color if the product has at any time been kept at the wrong temperature. You know, so many foods can spoil and the end customer will just take into consideration the final temperature. But, a guarantee of the correct temperature right through the supply chain really is something else.” Calum was getting quite animated. “We think some retailers may not like it but the premium ones will embrace it to prove their credentials. Then, the rest will have no choice but to follow.”

“When did you talk to us about it?” asked Thomas.

“Oh, a couple of months ago.”

“And you have not gone elsewhere with it yet?” Thomas inquired.

“No. Given that Calbury works so much with Marshfield, we prefer not to take it there. And, we really feel we need to work closely with a customer to perfect it. It’s exciting but a bit untried, so ideally we would like to see a launch customer prepared to invest in it. We have been hoping that would be Heartland.”

“You know, Calum, you and I should meet more,” smiled Thomas. “I think that together we might be able to cut through some of the red tape on things like this.”

“Music to my ears,” said Calum.

They returned to the conference room. The air had cleared a bit. The other team members were talking about the color-changing film, too. One of the Heartland people had remembered it from the discussion two months before. With a slight steer from Thomas and Calum, the meeting moved from a recrimination session into “How to compete with Calbury and Marshfield.” The plan was borne to co-commercialize the color-changing film. Both parties committed resources and investment. They also agreed to act rapidly.

Some months later, Laura found herself walking with trepidation into the presentation of the formal launch of the color-changing film to an awaiting world. She took her seat next to Scarlet, the CMO. This event was sufficiently high profile that both Thomas and Calum were the key presenters, rather than the functional leaders. They needn’t have worried though. The presentation was received incredibly well. The news went viral within minutes of it being announced.

That evening, Chuck Evans, the CEO of Calbury, was asked for a comment by a business reporter as he attended a reception. All he was able to muster was, “No comment.” Thomas chuckled when he read that in the news the next day. He could not resist picking the phone up to talk to Calum. By now, they were on very easy speaking terms.

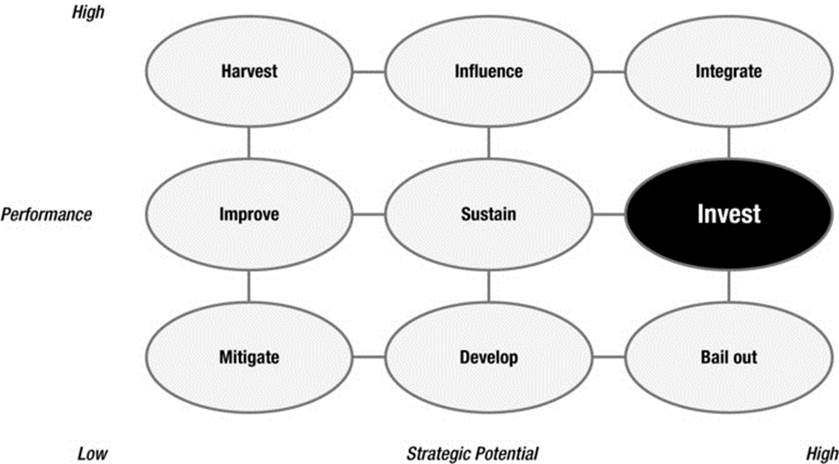

Characteristics of Invest Suppliers

Suppliers that fall into the Invest interaction model (Figure 7-2) provide a portfolio of products or services that could become game changing. Their strategic potential is very high. They offer great ideas and innovations, but then they stumble in some basic areas, such as providing continuous supply or consistent quality. These capability gaps limit the potential to achieve truly game-changing moves with them. Ultimately, they could reach Integrate status—but their potential for this rests on the relationship you build with them now and the extent to which they respond. Typically, exclusivity is not really important but rather the willingness of both parties to cooperate and drive capability improvements.

Figure 7-2. Invest suppliers on the strategy/performance axes

The Invest model can also include investment in development of new product or service offerings. It can be investment in new material or production technology. In some industries, such as aerospace, it is common for customers and suppliers to participate in new projects via risk- and revenue-sharing partnerships. Both parties contribute to development costs and share the returns. Typically, new programs require a major development cost and suppliers have some of the key expertise that is needed to support it. Original equipment manufacturers (OEM) will expect that suppliers commit both expertise and capital to finance the cost. The basic principle applied is that suppliers that have to make the most up-front investment are entitled to a proportional share of the revenue as the project realizes its goals. Revenue will be earned over the period that could be as long as 30 years, and profit increases toward the end of the product life cycle once both parties start selling spare parts. This illustrates a very nontraditional customer-supplier relationship. Both parties invest heavily in new product development, and if they fail, they fail together. The supplier has a strong incentive to make the investment. Often this is accompanied by additional investment on the OEM side to ensure that suppliers deliver the expected performance levels.

What Kind of Behavior to Drive

Ideally, an Invest supplier will aspire to Integrate status and will invest with you in building capabilities to achieve this title. It is OK or even desired for the supplier to be bullish about its future with you. But, it also needs to be able to look into the mirror and recognize the necessity that it improves. Provided this is the case, we recommend nurturing the relationship by investing time, money, and resources in developing the supplier’s capabilities to meet your needs. The best candidates will make capability building a top priority. Be forewarned, however, that some suppliers may spurn the help, believing that you are attempting to make them “captive” and to cut them off from wider market opportunities.

![]() Note Some suppliers may not appreciate their “Invest” categorization. They may feel that getting into bed with you now cuts off other opportunities down the road. In other words, what looks like a golden opportunity to you may not look so enticing from their point of view. You may need to make a good argument to attract their cooperation.

Note Some suppliers may not appreciate their “Invest” categorization. They may feel that getting into bed with you now cuts off other opportunities down the road. In other words, what looks like a golden opportunity to you may not look so enticing from their point of view. You may need to make a good argument to attract their cooperation.

The capability building will follow an aggressive improvement plan with a clearly defined target set and a roadmap on how to get there. To ensure success, the supplier’s leadership has to share this vision and cascade it through the organization. The purpose, or “Why?” for the capability building has to be clear. In order not to get off the path, these changes must be pushed with a high sense of urgency. You will also need to apply steady pressure. Identify tenacious change agents in the Invest supplier’s organization that will take the messages and influence the naysayer to remove the roadblocks for improvement. As you progress along the path, document improvements and provide areas for growth to the supplier so that it sees the return on the investment.

How to Work with Invest Suppliers

In some ways, the Invest model can be likened to a wedding engagement. You need to strike the right balance between nurturing the supplier, engendering trust, and overcoming fears of “capture.”

A transparent business case that both parties buy into will help alleviate supplier hesitancy. It should present a compelling return on investment for both parties. To make this work, you need to know what the current pain points are for your internal stakeholders—not just Procurement, but also Engineering, Product Marketing, Quality, and others. And to get your investment priorities right, you need to understand the overall impact, reviewing with the supplier the timetable to build capabilities in line with your expectations. In this model, it is essential that you stick to your commitments in order to reduce the risk to the supplier.

Implementation can be performed by the supplier alone if it has sufficient capabilities in-house; if not, you can assist by temporarily assigning your own resources or by engaging external help. Often these relationships will require you to have boots on the ground, meaning you send your own resources to the supplier’s site, be it an engineering group or a factory where it makes the products. This simplifies collaboration, especially when investing in making something new.

Governance

The Invest interaction model means that both parties have a vested interest in the collaboration. Building a supplier’s competencies is given the highest priority and both groups are focused on making the investment pay off. Typically, a joint steering committee is established to govern the process and track progress. Given the close cooperation, it is important that you also clearly define the parties’ respective roles and responsibilities to limit confusion.

Case Example #1

Let’s look at an example from the consumer electronics industry, which is known for having all of the production outsourced to contract-manufacturing partners. Relationships with suppliers need to be carefully managed to be able to deliver products to the market. The industry is further characterized by short product life cycles, with many products sold for only 12 or 18 months. One of the world’s largest consumer electronics companies, Apple, outpaced its competition by focusing on technological innovation, design, and corporate leadership. As with many other OEMs, Apple sold all of its in-house manufacturing capacity in the 1990s, and it has relied since then solely on outsourced manufacturers.

Following the huge success of its products, Apple decided to consolidate its supply base of contract manufacturers (CM) to allow for better control of product cost, lead times, and quality. One particular CM, Hon Hai Precision Industry (better known as Foxconn), had the potential to become Apple’s single most important contractor due to its flexibility in following the company’s guidelines. The resulting success of Foxconn in terms of cost-effectiveness and market flexibility depends largely on Apple’s strategy of investing heavily in the relationship. In its megafactories, Foxconn was able to reorganize production lines, and their staffing and logistics, in a very short time at the lowest cost. At the same time, they followed Apple’s rigorous specifications of price, product quality, and time-to-market.

Let’s look more closely at examples of how Apple invested in Foxconn to increase its performance. First of all, Apple’s teams of engineers and supply chain managers were sent as a task force to Foxconn’s factories in an effort to improve production and quality control. The dispatched teams worked together with Foxconn as long as needed to resolve any manufacturing and supply chain issues. The way they worked together was as one team with clearly defined roles. In addition to investing resources, Apple decided to invest billions of dollars in a production line. A look into its balance sheets, specifically at the data for machine and equipment expenditure, reveals that there is a consistent pattern of investment in equipment and tools installed in its supply base. The technology giant has clearly been pursuing a strategic goal to extend control over the supply chain. The expenditure has increased to several billion dollars per year, and the bulk of the spending is on product tooling and manufacturing process equipment. It has been rumored that in one year, Apple has invested ten times as much in computer numerical control (CNC) machines and tooling installed at Foxconn’s factories than it has in its own retail stores. By revolutionizing the use of CNC machining and anodizing in the computer electronics industry, the company has been able to offer very unique product designs as one of its major market differentiators. The advantage is a single-piece unibody design, making the housing seamless and beautiful, which is possible because the CNC solution allows the number of build parts to be reduced dramatically in the case of a unibody notebook chassis. The holes can also be produced to a much tighter tolerance than if they were simply molded into the part. The whole assembly process is also made easier and the manufacturing becomes closer to full automation because CNC machines run in lights-off factories. The latest example of an innovation is Apple investing in robots and placing them in Foxconn’s megafactories. By investing so much in robotics, the company will retain its leadership in manufacturing technology, product quality, and worker efficiency for many more years.

Case Example #2

Another example of the Invest interaction model can be found in the automotive industry. As electric cars are becoming mainstream, many companies and groups of engineers are looking for ways to establish themselves in the industry. They are reshaping the mechanics of the automobile, as many old paradigms do not hold any more. If we wanted to make a bold claim, we could go as far as comparing an electric car to an oversized cell phone: in the end, it is primarily a huge battery and the electronics to operate it. To design a mainstream electric car, you need a more optimal mileage range. Some of the improvements carmakers are pushing include improving the weight of the car (the lighter the better to minimize energy consumption), improving the aerodynamics of the car, and extending battery life by providing the ability to recharge while driving and larger and lighter batteries.

BMW decided to bet on the use of carbon fibers to significantly reduce the weight of the car. Based on initial design estimates, the company expected that using carbon fibers would reduce the weight of a small electric car, designed for use in the cities, by 500–800 pounds. Today, most cars in general are made of steel or aluminum, and carbon frames are half the weight of steel and two-thirds the weight of aluminum. With much less weight in the car body, BMW decided that it could put a much larger battery inside to provide greater mileage. Having very limited experience with the material, which was until then used for some high-end sports and racing cars, this was a risky bet. What was needed was a supplier with relevant experience and a willingness to make the technology affordable for mass production. The company reached out to SGL Carbon, one of the world’s leading manufacturers of products using carbon fiber. The manufacturer recognized the value of the opportunity and decided to participate in an investment in a state-of-the-art factory in Moses Lake, Washington, that would produce carbon fibers. This location was picked for its cheap and readily available clean hydropower from the dams of the Columbia River. The production of carbon fibers is the most energy-consuming process in the entire value chain, so this had huge cost implications.

The joint partners set up an entire value chain process: the raw materials would be imported from a Japanese supplier and the spools of carbon fiber from Moses Lake would then be shipped to plants in Germany to be woven into fabric and later molded into parts at BMW’s factory. Factories were set up to mass-produce the ultra-lightweight body components from carbon fiber-reinforced plastics and make the new technology affordable. Indeed, this joint venture is expected to set a precedent for the use of carbon fiber in mass-produced vehicles, a milestone for the automotive industry.

A Challenge for Heartland

Despite the air-conditioning running at full speed, Laura felt perspiration building up on her forehead. When Tracey Lin, the head of Heartland’s North American Food Division, had asked her to support a request for benchmarking procurement with EATing, the largest high-end grocery chain, she had assumed it would be a walk in the park. Granted, there had been some hesitation at the prospect of helping a customer become smarter in Procurement, but Thomas had quickly waived concerns with, “If we don’t do it, somebody else will. And we have more to gain than lose from opening up to them.”

What Laura had not expected, though, was the aggressiveness with which the EATing people had approached the benchmarking. They had sent a long-and-detailed agenda of what they wanted to see and they had proposed breakout groups to discuss certain topics more in depth. Then they wanted the breakout groups to be coheaded by EATing and Heartland representatives. When it turned out that most of the EATing representatives were former consultants from top firms, Laura started to have doubts as to whether her own people would be an appropriate match. After all, her program to upgrade the overall caliber of Procurement talent had only just started.

Today, Laura had to face a visit from EATing to discuss the benchmarking. Their delegation turned out to be overseen by EATing’s head of category management, Spike Turner. That, in turn, made the visit a top affair at Heartland. After all, EATing was the company’s second-largest retail customer, and Spike had never visited Heartland before. Even Tracey had second thoughts.

She had said to Laura, “I hope this is not about them assessing the effectiveness of our procurement. The last thing we want is for them to impose an improvement program on us and then squeeze us for the benefits.” After all, EATing had a reputation for being exceptionally ruthless with suppliers.

The meeting with EATing turned out to be even more challenging than expected. Laura’s presentation on Heartland Procurement best practices clearly had failed to impress despite her best efforts. Her war stories about introducing cost regression analysis to Heartland had been interrupted by Spike saying: “If I remember correctly, we introduced statistical tools to category management back in the early ’90s. There was a golden opportunity when the stock market was down and we could snap up some analysts from Wall Street for cheap. Retail is a cutthroat business with razor-thin margins, you know. Obviously, Heartland is far more comfortable than we are.” It took a couple of seconds for Laura to compose herself after this. She knew how to deal with high-ranking supplier executives and board members, but this was different. If this meeting went sour, a lot of revenue would be at stake.

“Spike, I sense that you are not getting what you are looking for out of this meeting. Please help me to better understand, what would make you deem the trip to Fort Wayne worthwhile?”

Before Tracey could say anything, the executive responded: “OK, let me be frank with you. We have run out of ideas on what to do on the procurement end of category management. We know for sure that we at EATing are better than all our competitors, yet our margins are still disappointing. So we have turned to our three biggest suppliers for inspiration. You are actually the last one we are talking to. We have drawn blanks in the first two meetings and quite frankly, this looks like another one. Don’t get me wrong, what you are doing here is all very good and admirable and so on, but there is nothing exceptional, nothing we can transfer to EATing. So for the sake of your time and our time, it might be best to wrap up.”

Without hesitating for a second, Laura knew what to do. “Well, there is one more thing that I have not talked about. It is brand new and we have not fully gotten our heads around it. We call it TrueSRM.” She then went on to explain the story of the voyage of discovery that Heartland had embarked on, including some of the key successes like the collaboration with Caledonian. The EATing delegation asked lots of questions and the discussion quickly veered away from the presentation slides in a highly positive way. The discussion extended way beyond the agreed time.

It was not obvious at the time, but ultimately, that day—and specifically that discussion of TrueSRM—would come to be marked in the annals of Heartland as the day that transformed the relationship with EATing. Given his experience and knowledge, Spike immediately understood the value of TrueSRM. What then followed the meeting was first a very personal thank you note from Spike to Laura, copying Thomas and Tracey. Then, Spike insisted on having Laura being present in all the meetings he would have with Tracey and every time they met different aspects of SRM were discussed. Finally, Spike reached out to Thomas with what he called a grand bargain. EATing wanted to launch a new comprehensive line of organic food. It believed that Heartland, despite not having the strongest credentials in that segment, would have the muscle to pull this off in a way that would leave little room for competitors. To Laura’s delight, the program would be code-named “Invest.”

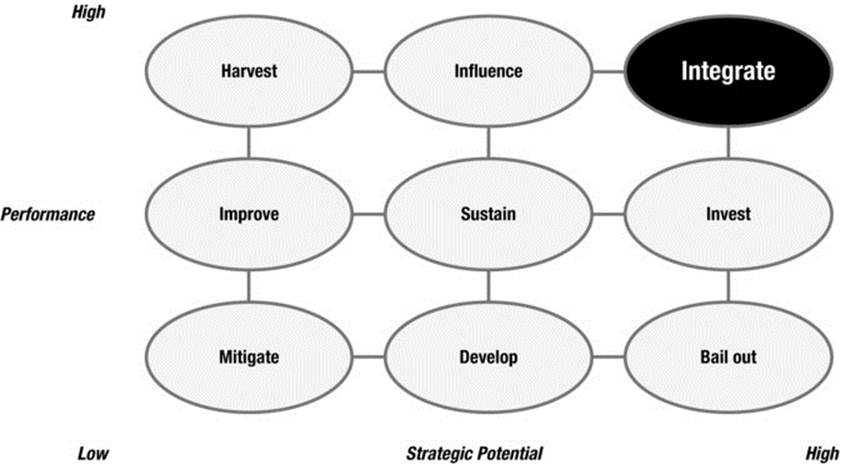

Characteristics of Integrate Suppliers

Together with Bail Out, Integrate has the lowest number of suppliers in the SRM framework—but these suppliers are really handpicked. For a company with 1,000 suppliers, we would expect to find a handful of suppliers in this interaction model. Some companies may not even have one of them, as this model requires highly specific interaction.

In the Integrate model (Figure 7-3), the goals of the two organizations are genuinely integrated, and they work together as equal partners. This is what distinguishes Integrate. In both the Influence and Invest models, there is strong collaboration, but the supplier and customer are not quite equals. They do not function as one entity and the relationship is not so all-embracing either. Colloquially, Integrate is a partnership with a capital “P.” Although an often-overused term in business, the true partnership is rare, being based on a multiyear, differentiated, and comprehensive relationship between you and your supplier to build an ecosystem that shapes the market. The supplier chosen for this model should be in your sweet spot: Its performance is flawless, and it holds the key to making you a formidable competitor by creating opportunities to grow revenues and profits while jointly shaping or reshaping the industry. You and the supplier will act very much like a single entity.

Figure 7-3. Integrate suppliers on the strategy/performance axes

It is, then, a very closely integrated relationship you build with suppliers, like a virtually integrated enterprise. Indeed, it is sometimes likened to a marriage in that it is a long-term, highly integrated relationship. In this integration, you would create a winning ecosystem to jointly shape the market.

To build and maintain such an involved relationship as the Integrate model requires substantial investment by both parties. Understand that the supplier that commits to this model takes on significant risk. By giving you highly preferential treatment, it could be limiting its own growth potential. Likewise, such concentrated, powerful Integrate relationships suggest that you should have no more than a handful of these suppliers on board.

What Kind of Behavior to Drive

There is only one right way to treat your Integrate supplier, and that is the same way you would treat your own factory. You pay it the highest respect, as it is key to making you successful. The preferred behavior of the supplier is to see the relationship as one ecosystem, or as an extension of its own company. Depending on each party’s capabilities, you want to define the roles to capitalize on strengths. The supplier should be involved in making product decisions, for example deciding which market segments to attack, determining the right product or service to offer and its target cost, how to design and manufacture the product or deliver the service, and so on. It needs to think of you not only as its most desired customer, but even more as a partner in crime. If a product or service fails, you will both pay the price for it. Your success will make the supplier successful. Encourage the supplier to be proactive and come up with proposals. Provide it the platform for their ideas to be listened to and dedicate resources to drive execution.

How to Work with Integrate Suppliers

A successful Integrate relationship thrives on a shared vision and willingness to act as one smoothly running, extended enterprise. Set the stage for this by driving consistency across your own divisions, functions, and hierarchies in terms of meeting needs, budgets, and timelines with this supplier. This model makes sense only if both parties benefit in terms of profit, revenue, and growth, which means they both should be mindful of market shifts and how they may affect the other. For example, should a supplier’s competitor offer the same product at a lower price, work with your Integrate supplier to meet this price by trimming specifications or improving productivity. Continually look for mutual cost reduction opportunities as well. When both parties understand each other’s core competencies, they can avoid duplications and start acting as a single entity.

![]() Note With Integrate suppliers, you meet challenges and exploit opportunities together in all regards. If a product fails in the marketplace for any reason, both should feel the pain and work together on a solution. To do this, you must understand each other’s core competencies and what each of you brings to the ecosystem that you have jointly orchestrated.

Note With Integrate suppliers, you meet challenges and exploit opportunities together in all regards. If a product fails in the marketplace for any reason, both should feel the pain and work together on a solution. To do this, you must understand each other’s core competencies and what each of you brings to the ecosystem that you have jointly orchestrated.

The integration makes sense only if both parties benefit in terms of profit, revenue, and growth, which means that both should be mindful of market shifts and how they may affect the other. You need to be able and willing to provide meaningful volume to the supplier and, in return, increase overall significance to its business.

Governance

Getting back to building a highly integrated relationship with one of your suppliers, commitment can be demonstrated by defining a mission statement that declares the scope and purpose of a winning ecosystem. To make this relationship work, an executive sponsor is needed on both sides—chosen not based on hierarchy level but rather on their ability to drive alignment across functions, business, and hierarchies.

The effort will focus on jointly managing selected portfolio segments or even the whole portfolio, as we have observed in some cases. Manage the relationship very closely. Do not shy away from putting your A-team behind it and encourage your supplier to do the same. Encourage very close collaboration and, if needed, colocate joint teams close to decision makers. Schedule regular review meetings with management and executive sponsors, and foster a candid exchange of dialogue to eliminate any roadblocks to success. Typically, we would expect these to be needed on a frequent basis, depending on the speed of the industry. Weekly, monthly, or quarterly would be appropriate.

Case Example #1

Let’s look at an example from the beverage industry: energy drinks. This was a relatively new market in the 1980s, when there were two product streams: one focused on endurance athletes who needed to hydrate their bodies and provide a sufficient level of electrolytes during high-effort sports, such as cycling. A new use and target group then emerged in the late 1980s: nightclub goers who used energy drinks as a way to stay awake and alert throughout the craze of the night. The success of the latter was driven by a company that had all of its production and supply chain outsourced to one single company. That company was Red Bull and its then partner that remains today was Rauch. In the 1980s, Rauch, a maker of fruit juices that was founded after World War I, put its belief in a single-person company—Dietrich Mateschitz with Red Bull—creating a great marketing plan and becoming its sole bottler. In return, Red Bull agreed not to work with any other bottling company. Such a commitment was risky for both parties, but Red Bull’s product strength and Rauch’s distribution capabilities in 90 countries made for a powerful integrated approach across the two businesses.

Today, almost 30 years later, Red Bull enjoys the largest worldwide market share in its category, selling in over 160 countries. Nevertheless, the company has remained true to its mission, and it doesn’t own a single factory or truck to deliver its distinctive cans to the stores. The bottler Rauch has remained the sole supplier and still does not work for any other energy drink company. Almost half of the worldwide product is mixed and filled in two production locations in Europe.

So, what were the success factors of such a deep partnership and virtually integrated company? In the industry, there is an urban legend suggesting that this type of relationship is governed only by a handshake between both founders. While this would no doubt prove untrue for an enterprise of this magnitude—you can’t seriously expect to manage business without any legal contracts—in the case of these two companies the contract itself consisted of several pages and has been left in the drawer for several years. The two businesses are so well aligned with each other, understanding each other’s objectives and sharing key data, that they are seamlessly integrated. Having experienced hypergrowth in the second decade of the company, both partners had to review their combined ecosystem to allow for worldwide expansion. They considered the option of expanding and opening overseas operations, but in the end the close proximity of the Alps to pristine water and an extremely well-oiled system won. No other supplier, even some of the much larger bottlers with a much stronger presence across the world, could match what this partnership has built in the first ten years of its symbiotic existence.

Building on the success it had with Rauch, Red Bull is driving a model of very tight collaboration and building ecosystems with other key suppliers in its supply chain. The cans are still made by one main supplier that recently announced it would build a new factory literally wall-to-wall with the bottler’s factory to create a highly agile supply chain. The distribution is similarly managed by a single logistics group delivering the product all over the world.

So, with its size and financial muscle, why did Red Bull not buy Rauch and its other key suppliers? The answer lies in company culture and economies of scale. The energy drink is still a relatively small market for bottled drinks. Rauch remains one of the major regional juice makers, thus giving it large economies of scale as compared to if it were only present in the Red Bull energy drink business. Same goes for all its other suppliers. Red Bull, on the other hand, is a company very focused on its young, fresh, and sporty company culture and embracing marketing and advertising as its core competence. Mixing this with operations would require making sacrifices, and over time the culture would change.

The ecosystem that has been created in the partnership allows each organization to focus on its core competence and the value it brings to the overall “system.” This is advantageous vs. a full merger of the companies concerned, which would introduce greater internal managerial complexity.

“Worst Advertising” Label Rankles Heartland

In order to keep on top of things at Heartland, Thomas had developed the habit of maintaining a dashboard. It was just one sheet of paper on which he scored the different business units and functions across two dimensions—performance vs. plan. He overlaid this with his very personal gut feeling about the state of affairs. He had borrowed this approach from Autowerke’s chairman and had found it highly effective. Over the past months, Heartland’s soft drink division had persistently scored poorly across two dimensions. While the stagnating sales figures were a disappointment in themselves, Thomas worried most about the details behind the figures.

While Heartland’s iconic soda drinks still fared quite well globally, there was a worrying trend in North America. The age group of people between 15 and 25 were abandoning Heartland products in droves and instead favoring imported energy drinks. Heartland’s attempts to create its own brand of energy drinks had led to dismal results. Thomas was especially disappointed with the performance of his marketing team. After going through three agencies in two years, all they had to show was two Consumerist Worst Advertising Awards and horrific budget overruns.

Thomas knew that making soft drinks would do miracles for Heartland’s stock market performance and decided to take matters into his own hands going forward. From his days at Autowerke, he had excellent contacts at Greenway Electronics, one of the world’s biggest electronics device makers, which had taken over the smart phone market with its signature products. It took Thomas less than 15 minutes to have Tony Birch, Greenway’s legendary head of industrial design, on the phone. After exchanging pleasantries and praising Greenway’s latest smart phone, Thomas went directly to the topic: “Tony, I need your advice. We’re losing ground in soft drinks and somehow our people don’t get it. We behave like a sleepy giant, while our energy drink competitors are running circles around us. And our advertising campaigns are making matters worse, to be honest.”

“Yeah, winning the Worst Advertising Award twice in a row is quite something,” chuckled Tony.

“Exactly. And it is not for lack of money. We have poured a fortune into this. I believe we need an entirely different approach, and honestly speaking I don’t see how we can do this from our big corporate headquarters in Fort Wayne. We seem to be completely out of touch with how young people in this country live, think, and feel. You guys at Greenway have demonstrated many times that you are capable of reinventing yourselves. You are setting trends that the entire world is following. How can we replicate this at Heartland?”

“Thomas, if someone knew how to transfer Greenland’s magic formula to other companies, that guy would make a fortune writing books about it,” Tony sympathized. “Even I, being at the heart of it, can’t really explain it. But I might know someone who could help you. Here at Greenway we do a lot of creative things in-house, but we also work with some outside firms. There is this really creative outfit further up the valley. What they are doing is a bit hard to describe. It is somewhere between an industrial design house, a consultancy, and an advertising agency. They do really crazy stuff for us that I can’t even talk about, but I believe they are what you are looking for.”

Two months later, Product Maniacs, the firm Tony had recommended, was making a pitch to Thomas and his executive team. The company had requested to meet the team at 5 a.m., a highly unusual time, but had been unwilling to explain its motives. While two of the product maniacs were outlining how they would cooperate with Heartland in bringing them to the top of the mind of young consumers in America and elsewhere, Wim Kock, the founder, seemed to be somewhat absent glancing at his smart phone. Just as doubts were forming in Thomas’s mind as to whether following Tony’s advice was such a smart thing after all, Wim suddenly jumped to his feet and took the notebook from which they were presenting. “Gentlemen and ladies, here is the reason why we asked for a meeting so early in the day,” he said with a clear South African twang in his voice. The screen flicked to a live feed from what appeared to be a rocket launch pad.

“What you see here is the launch of a supply mission to the International Space Station by a private space transport company. I happen to know the owner and got the third stage of the rocket painted like one of your energy drink cans. So while your competition is spending millions to get to the edge of space with a balloon, we can get you into orbit for free.” In the background, the rocket lifted off the launchpad with the colors of the Heartland energy drink clearly visible. The powerful sound system in the conference room made the walls shake from the roar of the engines.

The video of the transport ship’s liftoff and its arrival at the station, with the Heartland logo in plain view, quickly went viral on the Web. As a consequence, Heartland’s energy drink sold out in most of the United States for weeks to follow. The impressive feat by Product Maniacs made the negotiations to strike a deal with Heartland a mere formality. From now on, Product Maniacs would run all product management and marketing for the energy drinks and Heartland would focus on the production and supply chain management.

Nourishing the Critical Cluster

In this chapter, we have described the three interaction models where companies will likely find fewest of their suppliers. But they are where you should place your bets if you want to make a difference by managing supplier relationships. The trick is to dedicate the right people to the job of providing the cross-functional expertise required to develop game-changing products and redefine your industry in such a way that you obtain significant competitive advantage.

We finished with the Critical Cluster to illustrate the uniqueness, intensity, and diversity of suppliers in this grouping. Far too often, companies jump to conclusions and nominate too many suppliers as Influence and Integrate candidates. In this cluster, however, the key to success is just to focus on a few critical suppliers who really matter. And this means to start off by deprioritizing many suppliers.