Institutionalization of UX: A Step-by-Step Guide to a User Experience Practice, Second Edition (2014)

Part II. Setup

Chapter 6. Standard User Profiles and Ecosystem Models

![]() Why knowledge of users and ecosystems is so important.

Why knowledge of users and ecosystems is so important.

![]() Working with various levels of user knowledge.

Working with various levels of user knowledge.

![]() The imperative of a shared standard.

The imperative of a shared standard.

![]() Static versus organically growing standard models.

Static versus organically growing standard models.

If you ask a good tailor to make a suit, the tailor is sure to ask you to come in for extensive measurements. Savvy executives know to hand the tailor a large tip to ensure that the job is done with great care—it’s that critical. Of course, you can create a suit without any measurements. There are common features, after all (most of us have two arms and two legs). A “one size fits all” solution is seldom flattering, however, and is not really able to fit all. It is the same with user experience design. Some features are common to almost all users. Most users can see color in the way that humans see color, for example. Even so, we can expect that roughly 9% of men will have some color perception weakness, and we know that putting red on black makes an effect called chromosteriopsis (making the object look three dimensional). Thus we can design based on these general principles—but not well.

Before 1995 or so, usability specialists concentrated on designing human–computer interactions. To build these focused dialogs, we needed to know about the user population, their tasks, and the environment they worked in. That was really enough when we were working with a computer that sat on a desk and was used by a single person, in an office-like environment. Today, of course, computing is much more ubiquitous. Computers are used everywhere and in much more complicated and interrelated ways. We now need to employ ethnographically inspired methods to understand many different users (or “actors,” in ethnographic terminology), interacting in diverse environments, using various artifacts (such as tools, art, and electronic devices), in a variety of scenarios. That makes it harder to “know your user”—but it also makes such knowledge far more critical.

I’m often asked why Apple Computer was so successful with the iPhone, iPad, and other such devices. Without question, these items are nicely designed. Apple also uses a lot of persuasion methods (such as keeping people waiting in line for purchases of new models). But the core reason for Apple’s success is that the company developed an ecosystem solution. It is not just selling a smartphone or a tablet; it is selling a device that allows people to access material in a huge application vending website, and go to a physical store where Geniuses provide support. In the same way, the Kindle Fire, which was initially an awkward tablet, sold millions of units because it was a portal to the Amazon.com environment.

Today it is essential to know your user’s complex ecosystem. However, that ecosystem is big, complex, and difficult for a single person to understand, much less research extensively.

The Worst Practice

Some user experience design practitioners are forced to design without good data on customers. Many have limitations because their organization will not invest in data gathering. This is particularly true with offshore operations, where the cost of travel becomes prohibitive. Some UX designers are just not trained properly. But the worst of the lot are those who think they already know everything and don’t need to learn more to do their design work. In all cases, these designers are able to apply general principles, so the user experience design work is not without value. Unfortunately, the resulting design cannot be adjusted to the real needs, workflow, environmental factors, and cultural perspective of the users.

You need to know your users. Here are a few examples explaining why this is important from my own experience.

HFI was once approached by a medical device company that had a moderately complex device that was successfully used in American homes. The company wanted to adapt the device for sale in India, China, and Brazil. It asked if HFI could translate the instructions for these new markets. Soon, however, the company realized that those ecosystems are different and actually required a substantially different design. It was initially surprised to realize that a continuous power supply, clean water, and literate caregivers were not always available in the new target markets.

I once designed a website that claimed that it had great security—the organization’s head of security taunted hackers to just try to get to his account. I thought it was a brilliant, persuasive design, but our research quickly showed that the design terrified local users. Rather than being more persuaded to trust the site, they were actually made more afraid by my design.

On another occasion, I was reviewing a Japanese website and was quite certain I had found a serious flaw. The user was constantly hounded by “Are you sure?” questions. The website included unnecessarily detailed instructions that went so far as to feature a downloadable PDF with a detailed description of each vegetable. Apala, however, pointed out that the Japanese have very high uncertainty avoidance. The level of detail and extensive instructions and verifications worked for the users. They even wanted the phone numbers of the company’s officers.

Even very smart and experienced user experience designers will do poor work without solid models of the user population and entire ecosystem.

Thin Personas: “Jane Is 34 and Has a Cat”

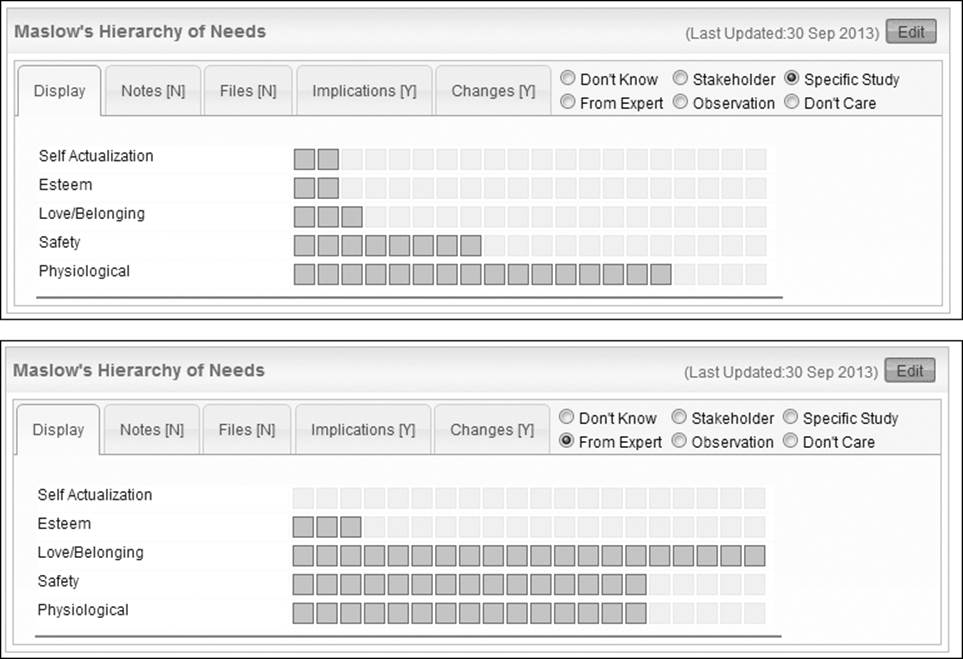

Some user experience design operations proceed with only “thin personas.” If you truly understand a set of people, you will understand the group in terms of many dimensions and characteristics. Most of these are best understood as distributions of data (see Figure 6-1). In the bottom distribution of Figure 6-1, we can see that substantial populations are focused on physiological, safety, and love/belonging needs. This is useful information—but in making a persona, you create a single fictitious person (occasionally a couple of them). A single person must represent the entire population. Such a persona is quite useful in sharing insights with armatures, but professional user experience design experts should always work with user profiles and not with personas.

Figure 6-1: Population distribution of needs, taken from UX Enterprise. Note that both of these charts show a few people focused on self-actualization, and many more people focused on physiological needs and love/belonging needs, respectively.

It is also important to include the things about the user community that are important to design. In a thin persona, we often are given very little information of use. If we are told that “Jane is 34 and has a cat,” what do we know that we can apply to design? We might suspect that our user population centers on an age of 34, but we don’t know if it includes kids or seniors. Also, knowing that your population includes kids or seniors changes a lot in your design. Moreover, while pet ownership is a recurring theme in thin personas, it does not impact design (with the exception of a few pet management-related projects).

Quality Personas

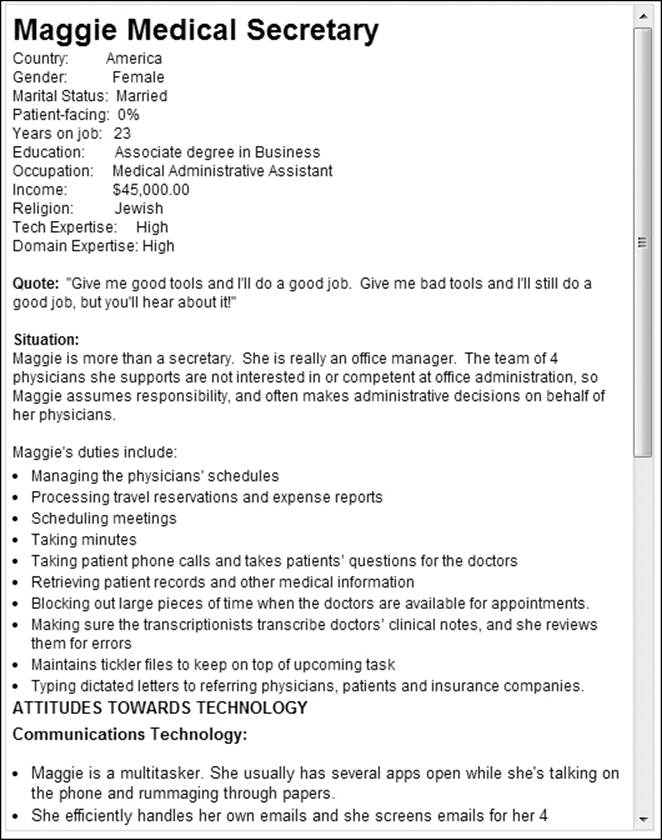

Even the richest personas have the problem of missing out on the insights you get from distributions. The good ones, however, can be a quick way even for a professional to grasp the user profile. An in-depth persona description will provide real depth in areas that matter to the design (seeFigure 6-2). A good persona may also characterize the fictitious user with a simulated interview and even a DILO (Day In the Life Of, pronounced “die-low”) model.

Figure 6-2: User profile, on sale at UX Marketplace

Quality personas are a bit useful, and we start to see the potential of having a centralized standard set. These centralized and standardized personas can reduce the amount of data gathering that teams have to complete. At least they start to reduce the amount of time spent repeating the same research over and over again.

While creating standard personas is useful, we hate to see this as a primary initiative in the institutionalization of a user experience design practice. Many organizations make this their first project, and at the end they just have a set of fictitious people. Someone always asks how that outcome has justified the cost of development. This is an embarrassing question, because those personas won’t do anything until they are applied. In addition, the decision makers in the organization are unlikely to understand and feel good about the expenditure.

The Best Practice: Working with Full Ecosystems

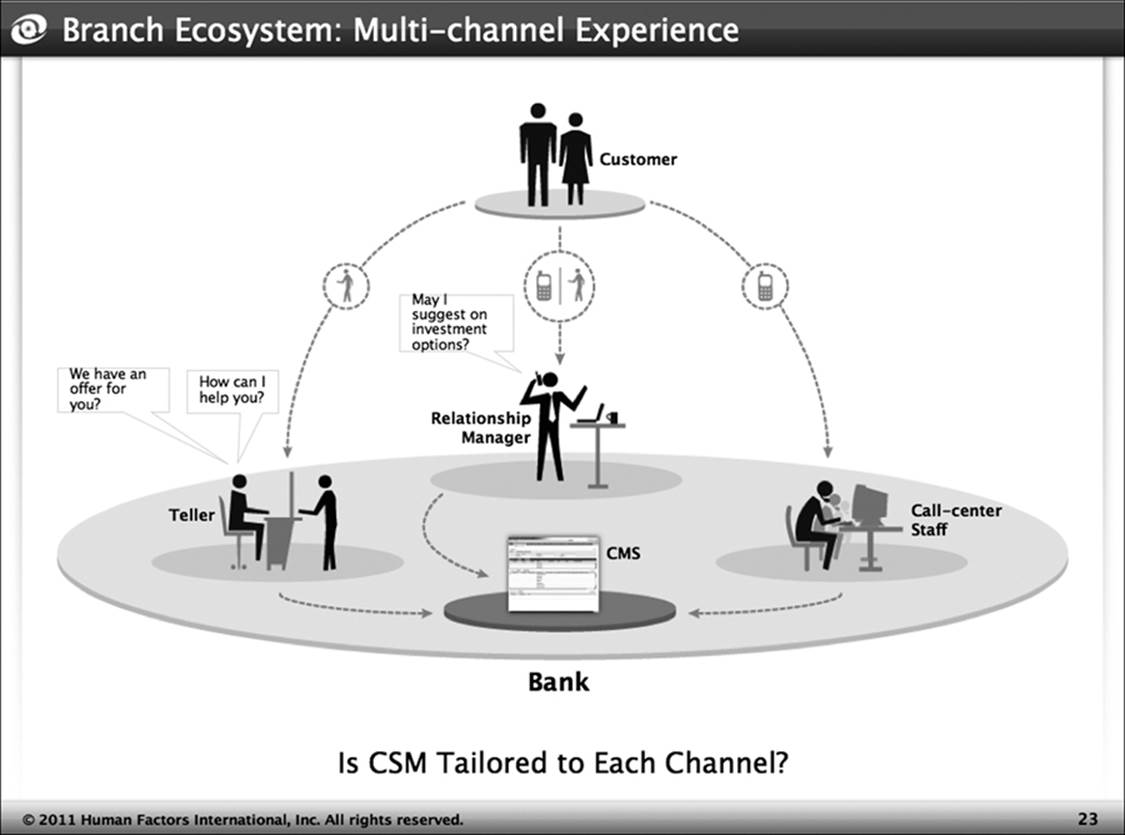

Today’s environment is characterized by truly ubiquitous computing. We develop applications that are used in a wide range of complex environments. We can no longer just look at one user operating one device. We need to design for complex ecosystems that have many user types (or “actors”), involved in many scenarios, in many environments, using many artifacts, and therein using our software (Figure 6-3). We have had to learn to apply ethnographically inspired methods to develop this type of understanding. Most real ethnographers, of course, spend months or years observing a culture—but we just don’t have that much time. Even so, we can gather this type of widespread understanding on a given context.

Figure 6-3: A high-level ecosystem drawing for a bank branch

The best practice of user experience design is to work from these ecosystem models and often design offerings that adapt to these ecosystems. Every organization has a range of ecosystems it tends to work with. To be able to claim that you truly “know your customer,” you must have a good model of all the major ecosystems that you target.

Standard User Profiles and Ecosystems

A thin persona takes very little time to develop, but you get what you pay for (though it might be better than nothing). In contrast, a serious user experience design team needs to get solid ecosystem models that can cost a lot to develop. Just studying one environment, such as an x-ray room in a hospital or use of mobile phones by middle-market digital natives in New York, can easily cost $250,000. Now consider how management will like having to pay this bill for each project. The costs become prohibitive very quickly. But there is a solution that makes it possible to work off of good data while keeping research costs to a reasonable level.

The answer to managing the cost of ecosystem research is to first maintain a shared standard for the commonly addressed ecosystems. Most organizations have a limited number of ecosystems that they address. A bank focuses on a branch, a high-net-worth client, a call center, and so on. An e-commerce company perhaps focuses on house renovations, with householders, contractors, families, and bankers as components of the ecosystem. A media company works on ecosystems of commuters, homemakers, and advertising buyers. There may be a dozen different ecosystems that are important—but the number is hardly infinite. In turn, we can create standard ecosystem models based on research and apply those findings to different projects for years. The cost of the research is amortized over dozens of programs, and now that $250,000 total cost for the research looks like $20,000 for each project, which is pretty easy to justify.

When we develop standard user interfaces, we always start with a generic set, if possible (see Figure 6-4 for examples). It is far easier to edit three generic interfaces than to develop those three standards from scratch. In the same way, a major benefit can be realized from the acquisition of baseline research that can then be fine-tuned to your specific environment.

Figure 6-4: A generic set of health care-related user profiles available for $900 from www.uxmarketplace.com

By acquiring a generic ecosystem model for your domain, you will have a much easier time creating a model for your specific organization. You can focus your efforts on what makes your situation special, instead of wasting time documenting common knowledge.

Acquired ecosystem objects can even be merged to provide a more sophisticated starting place. For example, you might need to create a health care ecosystem for China. If you can get profiles for only American health care users, you might be able to merge those American users with Chinese cultural attributes and obtain at least a generic starting place that will be closer to the ecosystem knowledge you really need.

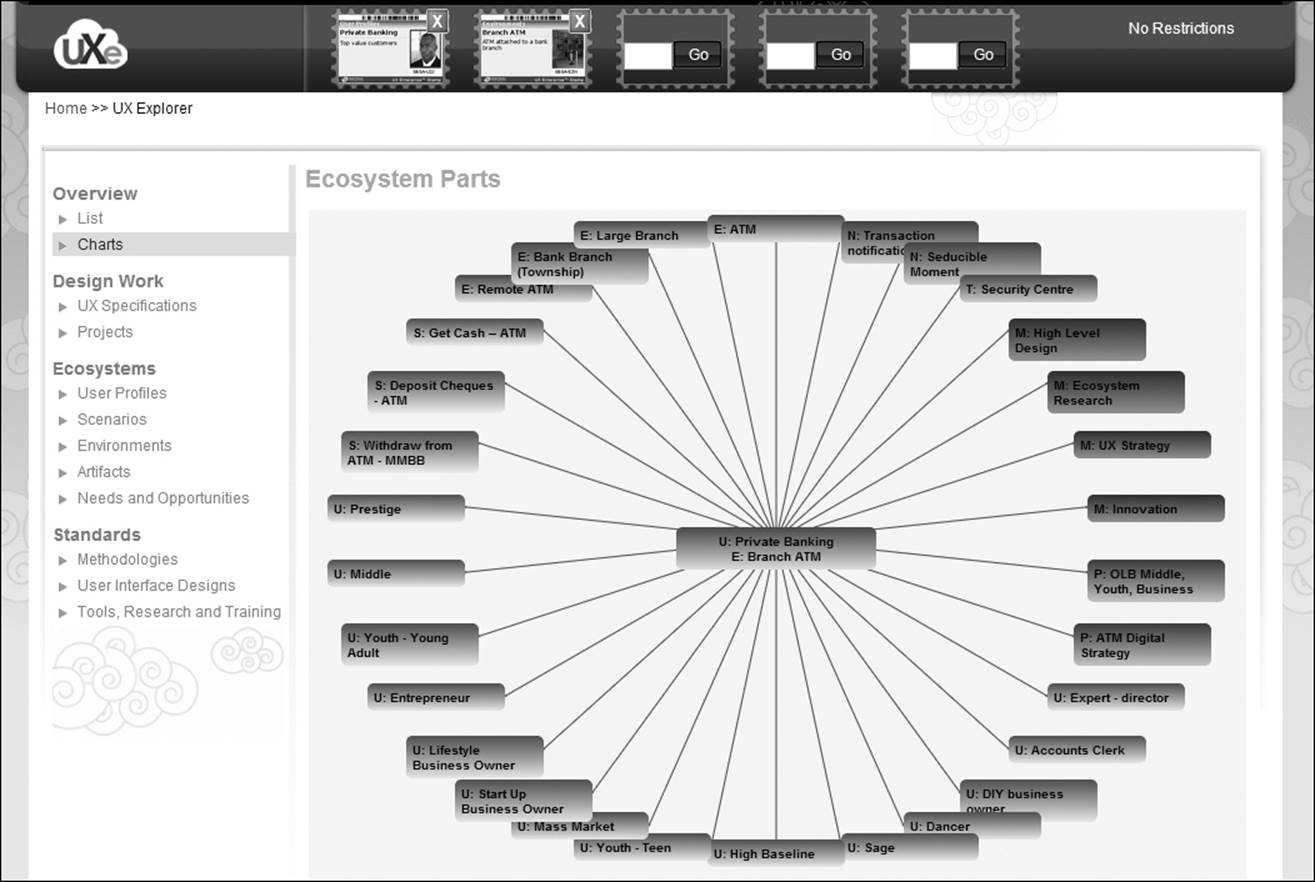

If you have complex needs, it becomes important to have ecosystem models that can be accessed using a relational database. As an example, let’s think about a pharmaceutical company. It might need to see the ecosystem knowledge about a surgeon’s use of a hospital pharmacy. There may have never been a specific study focused solely on this area, but a relational database can pull up all the ecosystem knowledge gathered from various studies that would apply. In the same way, a bank might need to know about high-net-worth customers’ use of a branch ATM (Figure 6-5). It is unlikely that a specific study will have addressed this issue, but there might be enough parts to pull together to get a pretty good idea of that ecosystem. Perhaps the understanding will not be sufficient to create a design, but at least it can be used as a starting place to do more focused research.

Figure 6-5: Even though a specific study with this focus has never been done, we can still see everything we know about high-net-worth customers’ use of a branch ATM using the UXEnterprise environment

At first glance, it might seem obvious which ecosystems will matter for your environment. A bank wants to know about branches; a media company cares about how people watch videos. In reality, the definition of an ecosystem quickly becomes very complex, because various ecosystems can be very different. The branch ecosystem consists of knowledge of everything around an environment; the watching videos ecosystem entails knowledge of everything around a scenario. In fact, ecosystems may be centered on almost anything. You might need to know everything about how a given design is used, or what a user experiences. You might need to know the focus of a previous study, everything around high-level design projects that have been completed, or everything around a strategic need (such as migrating customers to digital channels or reducing calls to the support group). And if this is not complex enough, you might need to know about combinations. For example, you might need to know about a user in an environment (e.g., a surgeon in her office), or about multiple users, using a device, while completing a scenario, in an environment (e.g., a family using mobile devices while watching movies at home). With these permutations, you can see why a relational database is almost essential for managing ecosystem knowledge.

Static versus Organic Models

Even if you have a very focused business, you will never really achieve a complete and final understanding of your customer. Your standard ecosystem models will always need to expand.

Today we live in times where every ecosystem is subject to change. There are changes in technology, so, for example, you might need to understand how mobile technology fits in, or near-field communication, or wearable devices. But technology is not the only source of change. There are rapid changes based on climate, and geopolitics, and shifting values, and memes. While your ecosystem models may be essential and efficient, you will still need to invest in periodic updates, just to keep up with changes in your field.

There is also a need to continuously get deeper and more specific insights. Obtaining such in-depth understanding is far better than doing the same research over. The standard ecosystems should provide solid foundational models, but you might want to conduct in-depth studies of how customers feel about using an ATM. That research will then need to be added to the existing ecosystem model. You will also find that good research tends to reveal a very complex and interesting set of driving forces, roadblocks, beliefs, and feelings. Beyond the obvious cost savings attributable to a shared and standard ecosystem model, there is value in letting research focus on more sophisticated issues.

Summary

Every organization should have standard, shared ecosystem models for the major user domains in its space. Development of such models eliminates the need for (and cost of) re-researching your customers. Even more important, it allows you to invest in research that gives a deeper and more specific understanding of your customers. You can also amortize the cost of the research across years of development projects.

For large-scale organizations, it is important to have these ecosystem models computerized so that they can be continuously upgraded. In addition, they must have relational database capabilities so that you can pull out just the knowledge of interest to your design project.