UX Strategy: How to Devise Innovative Digital Products That People Want (2015)

Chapter 10. Strategists in the Wild

Gotta stop drifting around

Kill this ugly duckling

We’ve got the power

And must not misuse it

Cuz life is short and full of thought

I use the power.

— THE FALL (1979)

UNTIL RECENTLY, THERE HAVE BEEN FEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR PEOPLE who practice some flavor of UX strategy to huddle together and compare notes. For this reason, I decided to hunt down some of these strategists in the wild to interview for this book. They range from business strategists to design executives and have worked on everything from shoestring to big-budget projects. My goal was for them to share their perspectives and techniques even if their strategic practices were different from my own. They were all asked the same 10 questions. Here is what they had to say.

Holly North

Born: Cuckfield, England

Currently resides: London, England

Education: BA in Sociology from the University of Sussex (England)

Figure 10-1. Holly North

1. How did you become a strategist and/or get into doing strategy as part of your work?

Well, I started out in television, working on the production side, and I think it was around the mid-’90s when I began hearing conversations about email and “the Web” but it wasn’t until I saw a web address on an ad in the London Underground that I thought things were really beginning to shift. I wanted to understand these new digital channels better so I made the jump to digital or “multimedia” as it was called back then.

I worked with a big creative agency in London and experienced a great variety of projects, technologies, and clients. It felt great to be at the beginning of something. Then, with the rise of interactive television, I saw an opportunity combine my television experience with my digital experience. Broadcasters were looking for ways to further engage and entertain audiences amidst increasing competition. Many interactive services were conceived after the show had been produced and felt very much like add-ons or an afterthought. We realized that we had to think more strategically about the integration of interactivity and television programming, not just in relation to a particular show but how it would complement a broadcaster’s business strategy. This meant stepping back and looking at the business and media strategies in the context of the market and what these technological changes were enabling. We were looking for trends, gaps, and opportunities and then develop a digital roadmap accordingly. We looked beyond just who the audience was and asked what they wanted to do and what they needed and within the context of use.

I studied sociology, which, looking back, was invaluable in preparing me for what I do now. Sociology requires you look systematically at human society; to examine the relationships between the individual and society and to better understand people’s motives, occupations, traditions, and cultures. As it turns out, this is great training for a UX strategist.

I didn’t set out to be a strategist — certainly not a UX strategist. I do think that in order to be successful one needs a level of strategic thinking, a strategic framework. For me, this means seeking out fact-based information, not relying on generalized theories, questioning assumptions. It involves compromise, understanding our competencies, challenging our thinking. More important, perhaps, it means determining what the right questions to ask are.

2. What does UX strategy mean to you? Is it a bogus job title?

Oh, I do think there’s a difference between strategy and design. A strategy sets out the plan and approach, and design is the tactical implementation of that strategy.

Honestly, I prefer the term experience strategy to user experience strategy. User experience strategy implies that it’s set apart from, say the business strategy, or the marketing strategy, or even the product strategy. And it shouldn’t be. Developing a product or service strategy requires that you understand the various touch points within the business: who is involved and the associated tasks or activities. This means talking to business stakeholders, sales and marketing, engineering but also to those you wouldn’t necessarily expect, like the office manager, the mailroom guy, or sales assistant. Strategy comes from this collective vision of the business and its customers. Perhaps it’s a matter of semantics, but when I hear people talking about a user experience strategy it’s often about the user experience vision, principles, and design objectives for a particular product or service. This is certainly a part of an experience strategy but should not be limited to it.

So no, it’s not a bogus title. But I do think we need to stop umming and aahring about our titles and our places in business. UX isn’t an emerging discipline anymore: it has emerged. Business recognizes the importance of UX. If we are still struggling to define ourselves, perhaps we not being strategic enough about demonstrating the value we bring to business.

So, as far as what I call myself...sometimes, I call myself an experience strategist and sometimes I call myself an interaction designer, because I am and do both of these things.

3. How did you learn about business strategy?

I have no formal training. I learned the fundamentals of business strategy on the job, over the years. I understood fairly quickly that to be successful I had to have a really good grasp of an organization’s business model and strategy, not just its customers or end users. I wasn’t simply the voice of the customer, although that was my role when I was starting out.

For the longest time, UX was in its own department, usually off somewhere with visual design. Technology sat somewhere else, as did the business folks. There were few integrated teams, so we were designing in a bubble. How can you possibly design a solution for a business if you have no understanding of what that business wants to achieve?

Not everything we do supports business priorities; we have to balance it with the needs and priorities of the customer or end user. Nonetheless, to support business priorities we need to understand them. Typically, they’re about increasing revenues, driving costs savings, and increasing market share. If you’re not supporting those, you’re not designing the right solution.

I’ve worked with some outstanding business strategists from whom I’ve learned a great deal, and I’m very grateful for that.

4. Do you think it’s helpful for UX designers who are aspiring strategists to get an MBA or have a business degree?

I didn’t go to business school, so I’m not entirely sure. I do wonder, however, if the time and financial investment is really worth it.

Honestly, I’m not sure if business school would have the same impact on the careers of aspiring UX strategists as it would on the careers of management consultants or investment bankers. If you are doing it for the big paycheck, go into banking or finance. If you want to gain the specialized knowledge and skills required to be a UX strategist, you won’t find it in business school, you’ll find it in the workplace and working with other UX professionals.

There’s also a plethora of UX-centric resources out there: free online resources, books (like this one, for example), conferences, master classes, as well as university degrees, which certainly weren’t available when I started out.

5. What types of products have you done the strategy for that were the most exciting or fun to work on?

Being involved in the development of a truly innovative product or service is certainly a lot of fun. But honestly, given the time, the budgets, or the aversion that many organizations have to risk-taking, it can be a challenge to create truly innovative products.

I was lucky enough to work with the Google Glass team helping to think about the customer experience strategy for part of the business, not that of the device itself. I enjoyed working with new or emerging technologies because they provide such great learning opportunities, and Glass was no exception.

Projects where I’ve developed a strategy that leads to the creation of value for both the client’s business and its customers are really rewarding. Or projects I’ve done that in some way had an impact on the industry, like when I was working with the first interactive TV service provider in the UK.

Frankly, most of the time it’s the client and the people I work with that makes an engagement fun.

6. What are some of the challenges of conducting strategy in different work environments (for example, startups versus agencies versus enterprises)?

Much of what we do is about aligning people, processes, and expectations, and this is challenging. I’d say people management can be a challenge within some organizations. I spend a good deal of time thinking about whom I am talking to and shaping my conversations accordingly — being aware of organizational politics. Organizational politics is another challenge. It influences what we do and how we do it, which could have an impact the quality of the work. I usually try to find out who the project decision makers are and what factors tend to influence them so I am better prepared. Adaptability is another key skill and being adept at building trust amongst those you work with.

Although exciting, startups pose their own set of challenges. There might not have been a UX designer or strategist in the organization before you, so a large part of what you do might be educating those around you on the value of user-centered design. Decisions about a product or service might already have been made before your arrival, which can make any change hard to negotiate, especially given that business owners are often product owners and feel a very strong sense of ownership in the product. People often wear multiple hats in startups, jumping in where needed which can cause some confusion regarding your role. Clearly communicating what you do and the value you bring to a project or solution, as a UX strategist, is key.

Time can also be a challenge. Startups often move at breakneck speeds to get a product to market, so you can be pushed to deliver quicker than you’re comfortable. It’s important to step back, slow down for a bit, and review where you are. Is the product or service supporting business priorities? Is it supporting the needs of the end users? Are you able to explain what the product or service is, in a way that your grandmother would understand?

7. Have you ever conducted any form of experiments on your product or UX strategy, whether it be trying to get market validation on a value proposition or testing prototypes on target customers? How do you get closer to the truth while you are conducting strategy?

Do we ever get closer to truth? What is the truth, Jaime?! To answer, yes I have conducted evaluations. The type of evaluation depends very much on the available budget, the available time, what is being evaluated, what point in the process we’re at, and who the end users are.

I think it’s vitally important that we evaluate our work as UX strategists and designers. We’re tasked with crafting an experience that other people will use. The amount of time and effort we put into this means objectivity might be a hard thing to maintain. We are often not the target audience either, so we’re not best placed to see the good, the bad, and the ugly. That’s why we need to put our work out there, at different stages of its development, for others to evaluate. And it’s not just end users you turn to for evaluation: it’s important that you regularly invite the business to evaluate your work because they ultimately own the experience.

I love user testing. I love sitting down with people and seeing how they react to something we’ve designed. No matter what stage of the process or what form the evaluation materials take. The outcome of these sessions helps make me and design teams more effective. And it can be feedback that comes from sitting down with friends, to more a formal response from a group of users in a usability lab. I don’t think I’ve ever conducted any testing or any research where I haven’t been surprised by something. No matter how good we are, we’re designing something for people, other people, so it’s inevitable that we’ll be surprised with how some people end up using the product...or not.

It’s important to spend time with people while they test something. This might be as close as we can get to “the truth.” For example, how do you know what people are looking at on a page before clicking, without watching them? You won’t find out what they are thinking, without asking them, and you won’t know to ask them unless you’ve seen them pause.

8. What is your secret weapon or go-to technique for devising strategies or building consensus on a shared vision?

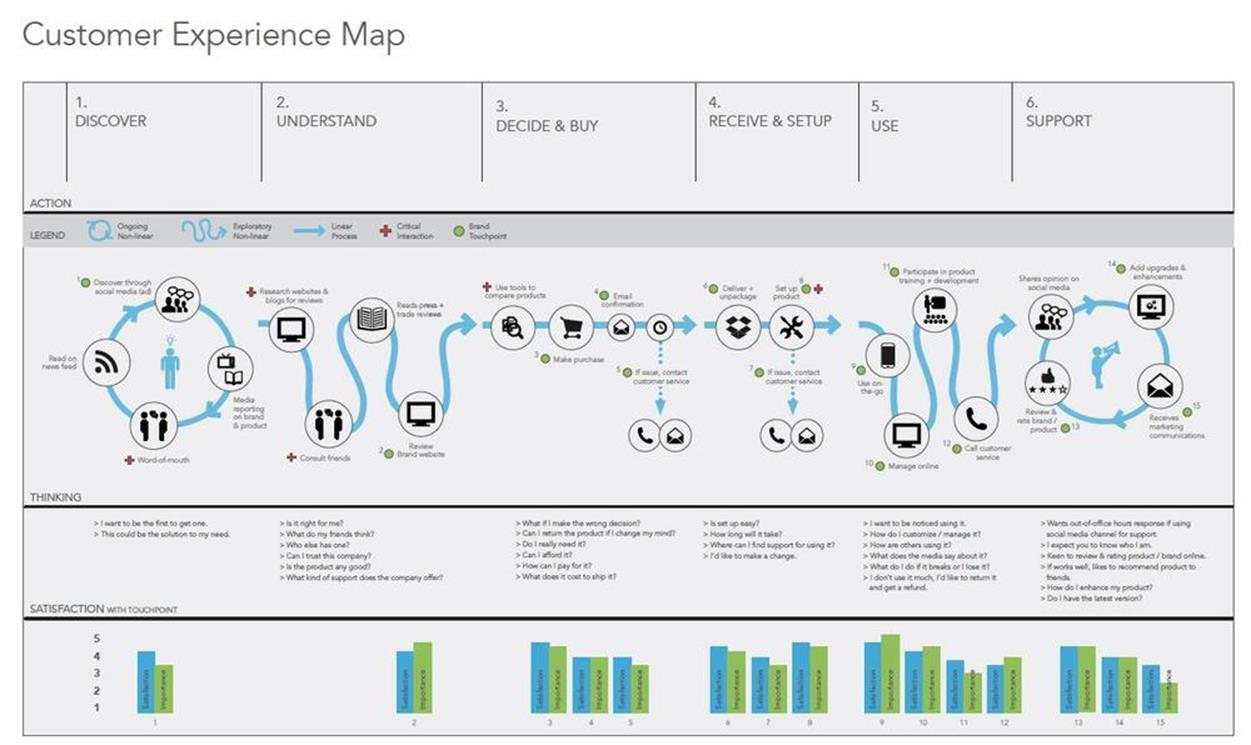

I would like to share what is called a user journey, or customer experience map (see Figure 10-2).

Figure 10-2. A customer experience map

An experience map is a strategic tool, rooted in user research, for capturing the complete experience a person might have with a product or service. It documents the experience from the customer’s perspective. What they’re doing. How they are doing it. How they feel about it. I use experience maps to help me understand the end-to-end experience a customer has with a brand. It helps me to see where the brand is creating value for the customer and where it is not. Ultimately, it’s a tool that helps determine the best strategy for delivering a seamless customer experience across multiple touch points.

I use customer experience maps to help focus a client on the customer. I bring stakeholders from across the business together and take them through the map. It’s a great tool for helping them understand the experience from the customer’s perspective and can be used to help build consensus on how to best serve customers at each touch point.

Depending on the nature of the engagement, I also might create a service map. It’s similar to a user experience map but from the business’s perspective. It captures how the business services the customer at each touch point. I layer this over the customer experience map to help understand what the business is doing, as a way of contextualizing the customer experience.

Each map tends to be a little different because they’re based on research, the results of which can vary significantly from one project to another. Maps are similar in that they’re visual representations of the user journey and tend to have similar phases within them. They often don’t represent a linear process, because customers tend to move back and forth through phases interacting with some touch points and not others.

The experience map in Figure 10-2 was part of an engagement with a retail client looking to refresh its brand and improve its overall customer experience, across its digital channels.

As you move from left to right across the map, you can see the six phases of the customer journey. These are the behavioral stages customers experience when discovering and interacting with a brand’s product. There is often continuity across experience maps with regard to these phases, but as I start amassing data about the purchase journey, I often refine or add to these.

For each phase, I ask customers what their goals are; what were their motivations. And then I try to discover the trigger or moment that moves them to the next phase. I jot down questions they ask themselves as they describe the journey, which helps me identify whether a brand is answering those effectively, or at all. I ask customers to describe their activities, interactions, and how long they take. I also ask them to rank their satisfaction of each activity on a scale of one to five, one being negative. Obviously, measuring customer experiences isn’t an exact science, because we’re trying to quantify a feeling, but it’s useful nonetheless. I often collect quotes from customers to accompany the rankings to help clients understand why customers ranked something in such a way.

There’s no right way to design an experience map. As I’ve mentioned, it depends on the nature of the engagement. I don’t treat it as a deliverable as such; rather, it’s a tool to move forward, leading to the development of strategy or design.

9. What is a business case or anecdotal story that you can share that walk us through the steps you have to go through when conducting strategy specifically for an innovative product?

I think it’s really hard to innovate and it’s something many clients want to do. It’s hard because it can require organizational or procedural change. Intellectually, clients understand this needs to happen, but emotionally it’s hard to commit to.

But it’s not Google Glass all the time. Innovation can happen in small, incremental steps. You can innovate around a feature or an interface or in phases, and ultimately it builds up to this really extraordinary, meaningful, hard-to-replicate experience.

I’m not sure that the steps I’ve gone through — when working on what were considered innovative products or services — have been wildly different from those on other products or services.

My process follows a similar pattern. I ask a series of questions.

I look at the business. Figure out what problem we’re trying to solve Determine the business objectives. Determine the measurements of success. Look at where the business is now and where it wants to be.

I determine who the intended users are. Without doing this, we’ll be designing for ourselves.

I look at the target market for the product. Who is or might be the competition? Is there a similar product on the market? What are the gaps and opportunities? What are the industry trends?

I look at the business capabilities and core competencies. Can the business achieve and maintain a competitive advantage based on its current capabilities and competencies? Do we have the capababilities to support the product now and in the future?

I often go back and refine what I’ve found with each new interview and with answers to the questions gathered, I review, analyze, and strategize. Gaps and opportunities will become apparent, creative solutions can be devised. Then, in collaboration with business stakeholders, priorities can be applied and an action plan developed.

10. What are important skills or mindsets for a strategist to have? Or what makes you good at your job?

You need a healthy dose of emotional intelligence. Nurturing relationships, building trust, and the ability to inspire people are what UX strategists do on a daily basis.

Be a critical thinker. Ask “why” questions and if you don’t get answers, reframe, and ask again. Don’t rely on the thinking of others and don’t assume. Challenge the existing opinions and beliefs of those around you...and your own.

Base your point of view on facts you’ve gathered from multiple sources. Evaluate and reevaluate to make sure your approach, decision, or design is still relevant.

Listen to those you don’t agree with. Are they making sense? Have you overlooked something? Seek opinions from people with different areas of expertise to gain different perspectives.

Own your decisions. Be prepared to be wrong. Be prepared to compromise.

Peter Merholz

Born: Santa Monica, California

Currently resides: Oakland, California, US

Education: BA in Anthropology from University of California, Berkeley

Figure 10-3. Peter Merholz

1. How did you become a strategist and/or get into doing strategy as part of your work?

I taught myself multimedia design in the ‘90s. My first formal role in software design was as a web developer, and then I transitioned from a web developer to being an interaction designer, and then from an interaction designer to a UX designer. Along the way, I realized that I needed answers to strategic questions, and that I needed to augment my “UX toolkit” to allow for more strategic thinking.

I truly became a “strategist” sometime around 2001 when I was at Adaptive Path. Adaptive Path was a very straightforward, very user-experience, design-oriented company. We were doing interaction design, information architecture, user research, and usability testing. However, to do the best design work that we could for our clients, we did more: we would ask them questions, so we understood the context in which the design work took place. We didn’t want to make a design for the sake of designing. We wanted to make the design deliver on some common interest, goal, or objective. And what we found was often our clients didn’t know the answers to our questions. They had never bothered to ask the questions themselves, and they didn’t understand how important those answers were to the shared design vision. So, we found ourselves moving upstream, doing what is essentially strategy work, to answer those questions. That’s how I became a strategist; to simply find the answers to the questions that I needed in order to do the best design work.

2. What does UX strategy mean to you? Is it a bogus job title?

You know, it’s funny. I just wrote a blog post about how there’s no such thing as UX design. And my point in that post was the design part of what we call UX design is typically just interaction design or information architecture. And the rest of what we call UX design is really just strategy and product management. However, at Adaptive Path, we talked a lot about defining what experience strategy and/or UX strategy was, so I think there’s validity to this concept. There is such a thing as UX strategy because product strategy and business strategy have failed in the prior decades to account for the user needs and awareness. To make sure that the user and the user experience was appropriately beneficial, we had to develop this thing called UX strategy.

In an ideal world you wouldn’t need UX strategy, because it would just be a component of your product or business strategy. We’re moving into this ideal world, I think. We’re seeing more and more often that UX is considered a part of a broader strategy. But, I think the separate and distinct concept of UX strategy was necessary for us — at least so we could focus on it — to shine a light on it and develop a toolkit to then wrap up in product strategy.

So, “UX strategy” is not bogus or overblown, but I do think that it’s a temporary artifact or a moment in time that we are in. If I think what UX strategy means to me, it is addressing those questions you need to answer and the answers to those questions that help inform your design. It’s not sufficient to simply have a business strategy or product strategy in the classical way of understanding your audience or total addressable market. You need to have a deeper understanding of your users, audiences, customers — whatever you want to call them — who they are, what they want, how they behave, and what they’re looking for. Traditional strategy methods, even if they talked about customers, didn’t really embrace deep customer understanding and empathy. So I think, what UX strategy does is it goes deeper into customer understanding. Again, what we’re seeing develop is a business strategy that is starting to appreciate that more directly.

3. How did you learn about business strategy?

I had no formal training or business strategy education. But something happened while I was at Adaptive Path. I was trying to understand how to do better UX design just after the dot-com bust happened. It was 2002 and there was a lot of soul searching going on in the UX community about proving our value. A common theme that we felt we needed to prove was the Return On Investment (ROI) of user experience. One of the opportunities we had at Adaptive Path was to explore these types of questions. I started digging into MBA-ish literature and then we got into contact with a professor at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, Sara L. Beckman (PhD, Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Stanford University).

She was one of first people who were trying to understand that design provides an interesting categorical advantage within business. One of her MBA students, Scott Hirsch, partnered with Adaptive Path to write a business paper on business value and how ROI drives user experience. With their advisement, we attempted to apply some real business thinking to our UX process. And so it was through these kinds of exposures that I was able to learn about business strategy and the kinds of things businesses tend to care about.

Honestly, business strategy is pretty straightforward: money in, money out. How do you reduce costs? How do you increase profits? At the heart of all businesses, that’s what it’s all about. If you can talk to a CEO or C-level people about how they can reduce or manage costs and increase revenues, or if they’re going to increase costs, increase revenue, whatever it is, that’s still business strategy. Tah dah! It’s not a black art.

One of the ways that I’ve been most informed about business strategy happened in 2005 when Adaptive Path hired Brandon Schauer, who has a master’s in Design and an MBA. Brandon ended up running Adaptive Path before it was acquired by Cap One. By working with him and being exposed to his methods, I was better able to understand the opportunity that design and UX has within a business context. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, we had already squeezed as much efficiency out of every value chain we could find. It was a lot about just-in-time manufacturing, process engineering; just squeezing, squeezing, squeezing, until the point of diminishing returns, and continuing to do that work. And so the opportunity was, well, how do we realize whole new value propositions. And that’s where good design comes in to point the way to whole new opportunities or differentiation within a space.

4. Do you think it’s helpful for UX designers who are aspiring strategists to get an MBA or have a business degree?

It’s not hurtful. Maybe it is moderately helpful. I’ve seen people who’ve gone through that experience and it’s been beneficial for them. But, you can also earn while you learn and come out in a very similar place. An MBA or business degree could be good for folks who are really transitioning from a craft form of a UX practice into something more strategic and need help making that shift. I feel like if you’re already doing it, even if it’s self-taught, an MBA isn’t going to get you much more. It could be useful depending on the school for making connections and meeting new people. Having a Harvard MBA or Stanford GSB certainly is not going to look bad on your resume. But that type of education is going to be a big financial investment too.

5. What types of products have you done the strategy for that were most exciting or fun to work on?

A transformative experience for me was working with Brandon Schauer at Adaptive Path on a project for a financial services client (not Capital One). It was in 2005, just when he joined our company. This project was meant to be a simple website redesign. But because we had a really savvy client, we were also able to do some strategic work, financial analysis, and modeling. This strategic work gave us a deeper understanding of the user research so that we could tie all these things together to help inform a potential strategic overhaul of the client’s entire service offering. However, as it turned out, they were not able to realize our vision because their organization was not set up to take on such a big shift.

What I learned on that project and some subsequent projects is that even if we delivered an amazing strategy to an organization, if the corporation is not shaped and its cultural values are not set to embrace that strategy, the strategy is meaningless.

The most fun strategy projects that I’ve worked on were vision projects. We did two for companies in South Korea, one that was the future of media, and one that was the future of commerce. These vision projects are awesome and they’re fun, especially when you’re working as a designer in a design firm. For one project we did a ton of trend analysis, trying to understand where these technologies were going, user behavior, and how that was evolving. That involved a lot of secondary research, which I’d say is not a typical method or UX practice. We read blogs, articles, and academic papers. We really just tried to soak in the space. We interviewed experts in media, we interviewed people who worked at YouTube, people who worked at product companies, people who worked in academia, looking at this stuff, trying to figure out — you know, where the future was going.

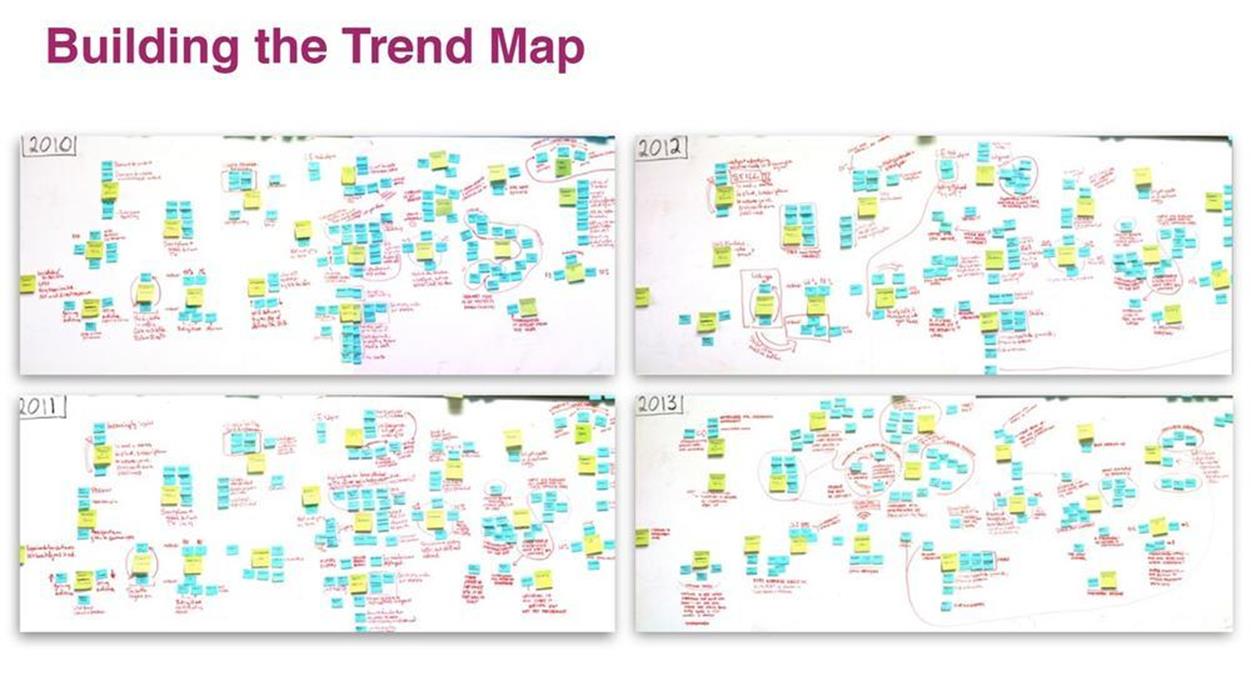

In digging through the trend research, we identified specific concepts, which we placed on blue stickies (see Figure 10-4). Then, we grouped those concepts around themes, which were yellow stickies. And we used red whiteboard marker to provide context and narrative for the concepts and themes. When we felt good about the map for a year, we took a picture of the whiteboard. Then, we erased all the marker lines and moved the stickies around (and added and removed stickies) to tell a story for the next year, and when we felt good about that, took that picture. So, the photos of the whiteboard became a time series of our trend forecasting, and fed into the Trend Map poster that we created (see Figure 10-5).

Figure 10-4. Trend analysis working session output

Figure 10-5. Trend forecasting slide

When those understandings paired with our design creativity and forecast of media experience in the midterm (three to five years), it was super fun. I learned a ton from that project and opportunity.

That’s a lot of the challenges for a lot of UX strategy work, particularly agency-based, where the impact of the UX strategy work is often unclear. I’ve not seen a lot of real organizational evolution. Since I’ve left the consulting world, one of the things that have been intriguing to me is how little interest Silicon Valley has in the word “strategy.” It’s almost like it’s a bad word, because I think it’s believed to mean a lot of chin stroking and not a lot of shipping, and there’s some truth to that.

The Lean Startup movement was responding to the same Silicon Valley mindset that is also kind of minimizing the value of strategy. The companies that practice strategy very seriously, such as Intuit, I don’t know what they have to show for it. So I’m kind of sympathetic to it. I think that there’s a role for strategy to play and explicit strategic efforts to play, in-house and within these tech companies, but there’s a struggle to find a right amount of strategy. You don’t want to feel as if it’s overwhelming, or it’s a waste of time and energy, or it’s too grand for us to realize, or that it’s just “Why did we bother?” Hitting that happy medium is an interesting challenge.

6. What are some challenges of conducting strategy in different work environments (for example, startups versus agencies versus enterprises)?

Within an agency context, it depends on the agency. At Adaptive Path, if you came to us, you were going to be embracing strategy. We weren’t the type of design agency that if we were to begin talking strategic concerns to you, you wouldn’t be, “Wait, what? No just push some pixels, will ya?!”

Some agencies have those challenges of moving upstream. But, I think for an agency, you have to set yourself up as a strategic provider, and if you attract clients, you’re doing strategy work. That’s relatively easy. Within that agency environment, and because of the way the projects tend to be structured, you can kind of create the safe space for strategy to be done. Now, the challenge for an agency, which I was referring to before, is that strategy can often feel irrelevant, by the time you go deliver it, or months later when you follow up on it, you’re like, “So what are you doing?” “Oh well, we had a reorg or this person left, or that person left, or what it is. We shifted this, that, and the other thing.” So the work you did just kind of doesn’t get used. So that’s the challenge for an agency.

The challenges for doing it in-house, at an enterprise, are for strategy to remain relevant. One method is to connect the strategic work to the production work, because those two functions tend to be owned by two different parts of an organization. So, the challenge is how do you make sure that your strategy feels actionable and operable so that your teams can draw and act on it. I think in an enterprise, you might get a lot of rich, deep, thoughtful strategy, but you might find that the market has changed by the time you’ve come up with all your strategic insight.

In the startup environment, the primary challenge for strategy is that there’s often no time to do it. To do strategy of any significant complexity correctly, it takes time, effort, and energy. In a startup you often don’t have that available excess time because you’re still trying to prove yourself, and just get a toehold. The strategic orientation within a startup has to come from the founders, as opposed to it being an explicitly separate activity that a UX strategist is conducting on his own. Having a UX Strategy and making sure you’re thinking properly about your UX as part of the broader product strategy is important. The companies that succeed are the ones that understand this, even if they haven’t practiced it explicitly.

The primary challenge is to embrace a meaningful and appropriate UX strategy, regardless of environment. The secondary challenge is making sure that strategic effort is operating at the appropriate cadence that your environment requires.

I’m now at a product company, Jawbone, which makes hardware. We can actually be more explicitly strategic than I’ve been able to be elsewhere. This is because for us to do a hardware product, it’s a huge investment. To mitigate the risk of that investment, we have to be strategic or we are going to be flushing a lot of money down the toilet. And so we have some room to be more thoughtful and mindful of our strategy.

7. Have you ever conducted any form of experiments on your product or UX strategy, whether it be trying to get market validation on a value proposition or testing prototypes on target customers? How do you get closer to the truth while you are conducting strategy?

The short answer to that question is “not really.” I see us doing that more here [at Jawbone] because of the risk, the up-front capital that it takes to launch hardware, you need to make sure you feel pretty good about it. So, because I’m new to this company, I need to validate earlier strategies before implementing them.

8. What is your secret weapon or go-to technique for devising strategies or building consensus on a shared vision?

Doing the right research, talking to the right kinds of folks, asking them the right kinds of questions, and observing the right kinds of behavior that can be analyzed and appropriately inform strategy and delivery. It’s hardly a secret weapon; a lot of people do it. Are you identifying your prospective audience appropriately so that your research participants are the kind of people who are going to engage once you have a product in the market? Are you asking the right questions? Observing the right behaviors? Probing them appropriately? You’re not just asking dumb questions. You’re allowing them to be who they are, but also recognizing you can’t do a purely anthropological study that can take months. So, to the degree that you’re forcing things, you’re forcing things appropriately, you’re getting the right stuff out of it. Are you then analyzing the results in meaningful ways so that you can develop appropriate insights?

I’m a fan of personas as developed by Alan Cooper (see Chapter 3). I don’t use them all the time, but when I do I like to study a full spectrum of user behavior. When I have the opportunity to look at the data from numerous user research interviews, I can identify the salient behaviors that stand out.

9. What is a business case or anecdotal story that you can share that walk us through the steps you have to go through when conducting strategy specifically for an innovative product?

For my last Adaptive Path project, we worked for a big global media brand client. We worked on its ecommerce platform — its online store. So, the strategy process began with research. This was a children’s media brand, so the research involved mainly moms. We did a lot of in-home interviews, talked to moms about buying stuff for their children, and focused mostly on gifting because of the nature of this brand. It wasn’t bought everyday. It was bought for special occasions. So we took that research and analyzed it.

We didn’t create personas for this project; we created profiles, very similar to personas but different. A persona is a face with a name you give it, and it’s meant to be a specific individual. Profiles are more categorical. We broke up these moms into four or five profile types. We had the mom who’s still a kid at heart and loves the stuff herself as much as the kids love it; we had the mom who’s more of the “I want to be an educator. I’m buying this stuff so I can create this world that my child can then succeed in”; then there was the mom that might be the kind of working mom who feels guilty working, so they’re spoiling these kids because they want to connect with them. So you come up with these profiles. From these profiles, we then told a series of stories and scenarios. The way we structured these scenarios was to focus on different technological platforms.

We had one mom that was all web, one mom who was all mobile smartphone, one mom who was all tablet, and then we actually used a grandmother who was kind of a spoiler; well, actually more of an indulger, who crossed all these streams. And we wrote scenarios of use. The grandmother one was actually, for the sake of this story, the one who ended up being the most interesting. We did talk to a couple of these grandma types. The grandma often doesn’t live near the grandchildren. Their children have moved away and have a family in another city, away from the grandparent. So, as we were writing this scenario, we have the grandparent in one city, the grandchildren in another city, and that was really interesting.

Okay, what can we do about that? Well, we write this story that’s around Christmas. The grandparent wants to get the grandchild something for Christmas. The grandparent can’t be there when the grandchild opens the present. So as we’re writing this story, what we realize is, well, what if you open this present, here’s a short form URL you can easily type into a web browser and you can get a video message from your grandma. There she is, Christmas morning, even though she can’t really be there. And so, that all came out of a strategic endeavor, research analysis, scenario development, essentially product design and development, leading to this particular feature that the client loved. They fell all over themselves and built the technology to realize it because they thought it was so appropriate for them. The client has a very clear brand, a brand personality, and this hit right at the heart of who the client is as a business brand. So that’s a story of from research to delivered feature where I feel that we had quite a bit of success.

You really want an understanding of what’s going on in the broader market. Now, that said, I think too often organizations look at what others are doing and feel they have to match that. But you don’t want to get caught in competition. Be at par. Parity is a red-ocean strategy; you’re just trying to line yourself up with everyone else there. You want to find that blue ocean. Now, I would argue that you wouldn’t want to find that blue ocean for the sake of finding the blue ocean. That is still being too cognizant of what your competition is doing. What you need to do is understand who you are as an organization, who you are as a business, and who you are as the people within that business so that you can see through to delivery.

I can see another company doing the same strategy that would perfectly fit its brand. But I don’t know if it’s what we should be doing, because it doesn’t seem to fit who we are. So, again, this is where I feel UX doesn’t really often embrace enough brand strategy. I think that there’s a reasonable antipathy to brand and branding within UX because I feel often branding is handled poorly. It’s very superficial. But, if you dig, you can appropriate brand strategy, issues of personality, issues of values that the company holds, issues of those characteristics that companies hold dear, and those elements of brand. UX needs to be very informed by that because releasing a product is hard. And if the people within the organization aren’t interested by the product they’re building, aren’t passionate about the product that they’re building, they’re only building something because they think that there’s a market for it, they’re not really going to dig in and do all the hard work needed to get that product to market as best as they could. It’s got to be a product the people that work there want to feel like they would use.

10. What are important skills or mindsets for a strategist to have? Or what makes you good at your job?

It is about a kind of mindset that you should possess where you can understand the parts and see how these parts fit within the whole. I became a strategist because I can’t help but think about design in a systems context, a design within a broader context. I have a systems mindset whenever I approach anything. And it was in order to satisfy my systems mindset that I realized I needed to embrace strategy, because I needed to understand how the context of the work that I was doing fit within this broader system.

A strategist also needs to be able to be persuasive, so you need to have good story-telling, communication, and presentation skills. You need to be able to bring people along in a story of engagement. Strategy tends to be abstract, so you need to be able to make that concrete so that other people can have a visceral response to it. Strategies that remain abstract tend not to take root, so another skill for a strategist is the ability to tell the story. To shape a narrative; to connect with an audience.

Milana Sobol

Born: Kazan (Tatarstan), Russia

Currently resides: New York City, US

Education: BA in Neuroscience and Economics from Brandeis University, MA in International Finance from Brandeis International Business School

Figure 10-6. Milana Sobol

1. How did you become a strategist and/or get into doing strategy as part of your work?

I had a startup right after business school where I had to do basically everything and wear many hats. We built a product from the ground up, so it became clear to me very early on that without a proper vision and a strategy to get there, we would be going around in circles. So I really learned about strategy on the job.

The startup was an online music distribution platform for unsigned musicians. It happened just as the music business started to unravel and everyone wanted to challenge the ways that the record labels did business. The strategy focused on understanding our audience (musicians) and their unmet needs online in the context of what was possible to do with the technology at the moment. We had to think about ways we could facilitate the digital tools for this new era so that these musicians could have more control over their art and the product they were making. But at the same time, we had to do that in a way that the business could make money. Strategy is not just about the product vision. It’s also the practical roadmap to get there; you have to think about both the end user and the supporting and sustainable business model.

When I started out, I wasn’t initially very good at balancing all the pieces. I didn’t understand how all the parts, business, design, and technology, came together so my planning and decision-making had holes in it. But I learned from my mistakes and was eager to try that role again in a more structured environment with better resources. So as I was exploring what to do next after the startup, I specifically sought out a position involving strategy in an interactive firm because I wanted to solve problems and build real products but in a creative environment.

2. What does UX strategy mean to you? Is it a bogus job title?

No, absolutely not. Over the years in both agencies and startups, I worked with many different types of UX strategists. There are some who think more like designers, and others who are focused on the business side of things. I consider myself more of a business strategist, and I really work the best with a solid UX strategist or very experienced designer. We need to work together to realize what the product does for the user and how do we make a business out of it. I tend to have some very basic ideas about how the product functions and the overall interaction experience, but I can never really think everything through at that granular level the way UX strategists and designers do it. So for me now, as a business owner and business strategist, the UX strategy is the core of everything we do, because in our case, the service is the product. It’s not like we are just a touch point for the customers along their experience with our business. Our product is the digital product. It is the service. It is the business. So we have to get it right, and it has to be delightful, and people will have to want to use it, and not just need to use it.

3. How did you learn about business strategy?

I learned most of what I know about business strategy in the first seven years after school just by constantly putting myself in the environment where I actually didn’t know anything about anything and had to learn about it. I had some academic credentials to get into it, but it didn’t mean that I really knew how to do it in a creative agency environment. I had gone to business school and took a lot of challenging courses at a good university, so on paper I seemed qualified for a strategy position. But to be honest, when I first walked into a professional environment, I didn’t really even know how to do the competitive analysis properly at the level required in product thinking. My training was more in finance.

When you are fresh out of business school, you want to do things in a very business school-y, academic kind of way. Basically, I had to learn from scratch. It was probably by the time I had done my twentieth business analysis/strategy presentation that I felt like I finally got it. It took some time before I truly understood how to put together a good story that was going to inform both the business goals and the design. But what I learned was not how to think analytically. That I already had. I learned how to tell a story. In a creative business, business strategy has to add up to a simple story about the product opportunity.

4. Do you think it’s helpful for UX designers who are aspiring strategists to get an MBA or have a business degree?

No, absolutely not. I think what is required is that they spend time with their colleagues in generative meetings. They really need to learn how to talk to clients and sincerely listen to their business problems. Being a good listener is absolutely essential. So, a degree in psychology might be more helpful than an MBA. I do think it is helpful to take a couple of business classes to learn and practice systems thinking and a framework approach to problem solving. Strategy is mainly about simplifying the chaotic and the complex into a simple diagram or a statement that everyone on your team can understand and get behind. Some people are naturally better at that kind of thinking and others are better at creative thinking. I find it’s very rare to find people who are super creative and analytical at the same time. Those people are very unique.

In my experience, business school is only a requirement if you want to get a really big corporate job. Having an MBA at a Fortune 500 company might be environmental requirement, but I don’t think it’s necessary for the creative world. I learned a lot by looking at the decks of strategists whom I respected and saw how they told the “business stories.” As I mentioned before, that type of storytelling is not something you would perfect in school.

5. What types of products have you done the strategy for that were the most exciting or fun to work on?

What I’m working on right now is probably the most engaging for me. But again, that’s because I’m the product owner who has a lot at stake. I think you have to have a different level of commitment not just when your name is on the line, but also all your finances and everything else. Perhaps that risk factor is what makes it very engaging.

In the agency world, you often do the strategy and sometimes you see through design, and in rare cases, you see it all the way through the build, but almost never do you then interact with the clients day-to-day to see how it really affects their businesses. With working in client services, sometimes you get feedback after delivery and you do postmortems. But it’s after your work has been delivered to your clients and the project is over. When the strategy is out of your hands, then it really becomes their baby. And the outcomes depend on what they do with it and how they market the product. And by that point, it’s really hard to isolate what worked or did not work. Was it the strategy or the design or the technology or the marketing? If the strategist is not involved throughout the process, she can’t really be held accountable. For me, that’s a bad thing because being able to be involved in the final outcomes is what motivates me.

So, right now I am building a product that we just put out on the market and I could immediately see how people reacted and how they use it. We spent nine months making assumptions and building a product based on our best thinking, and then, in a matter of days, we finally get some real feedback from real users. That is very satisfying, even if the feedback is not always positive. And believe me, it is not always positive. Through this direct learning, I get to iterate on the original idea with real people. The complete feedback loop is what makes it the most interesting product.

6. What are the some challenges of conducting strategy in different work environments (for example, startups versus agencies versus enterprises)?

Politics are always tough, and politics always come with the territory of any business that has more than three people. So with all kinds of enterprises and large clients, politics play a big role. You often deal with the budget that comes from a marketing department, and they have their own agenda. Often you are really building a product that’s informed by the business/product group, but then the business group is not actually involved in the strategy conversations. In that case, the challenge is to navigate all of that to make everybody play together.

A startup can have its own issues. It can be a little lonely. If you start small, there are only a handful of people you see and work with, 24/7. It can become too focused and sometimes you just wish, “Oh maybe we are tired and just need a fresh opinion.” Ultimately, until you start making a profit or get funded, the resources are always constrained. You don’t have people focusing on what they are best at, only. We all wear many hats.

I think that’s why agencies have the best balance. If you’re in the right group of people where you have the diverse and qualified team, you have feedback from the UX strategist, the business analyst, and all the different types of people that make your team well-rounded. When there is proper time to think and enough different perspectives, it fosters an environment where you are able to have enough points of view to really bring out great ideas.

7. Have you ever conducted any form of experiments on your product or UX strategy, whether it be trying to get market validation on a value proposition or testing prototypes on target customers? How do you get closer to the truth while you are conducting strategy?

The best example I can talk about is what I’m working on now, which is a mobile productivity app. I’ve done a number of tests with focus groups at different stages of development, from ideation, to prototypes, to the final product. We had an initial group of 20 people, a mix of potential users defined by background, needs, and behavior, that we showed our paper prototypes to first. This was helpful because in the conversations with potential users we got a chance to polish our own ideas to see if people are translating what we’ve created to what we intended to create. Do they get the overall concept?

The second level of testing was done with a couple of different clickable prototypes. We had a diverse group of people play with the apps and talk to us about what they liked and didn’t like, both about the concept and the execution.

The real test came when we actually launched the app and did a little marketing. Then, we had a much larger sample of 1,500 people using the app for a number of weeks. We did a survey online to understand why the users who were deeply engaged with the product love it and why others don’t. During this testing period, we continued to learn about what features they felt are missing and what users found confusing. It was not full-blown user testing, but we were able to gain insights that were super enlightening.

However, you have to take a lot of the feedback with a grain of salt. Some people are just mean and will say, “This thing sucks. I don’t know why somebody would build something like this. Nobody wants to use this.” But then I had few dozen people say, “This has become my favorite app. I use it every day.” The feedback that mattered was from those people who took the time to explain to us exactly what features they liked or didn’t like and why.

Even when we just showed very high-level concepts of the product, we saw that a lot of people were getting what the product was and validating that they would use it the way we had intended. That was when it felt like the strategy was correct. This was crucial because we did a lot of research to understand the opportunity space and needed to know that people wanted to have this product. We had certain assumptions that the strategy was initially built on, but as we refined our ideas through the various levels of design and testing, our strategy became more and more clear. At the end, we could clearly articulate what the product that we had built is, who wants to use it, and why. And we had real data to back it up.

8. What is your secret weapon or go-to technique for devising strategies or building consensus on a shared vision?

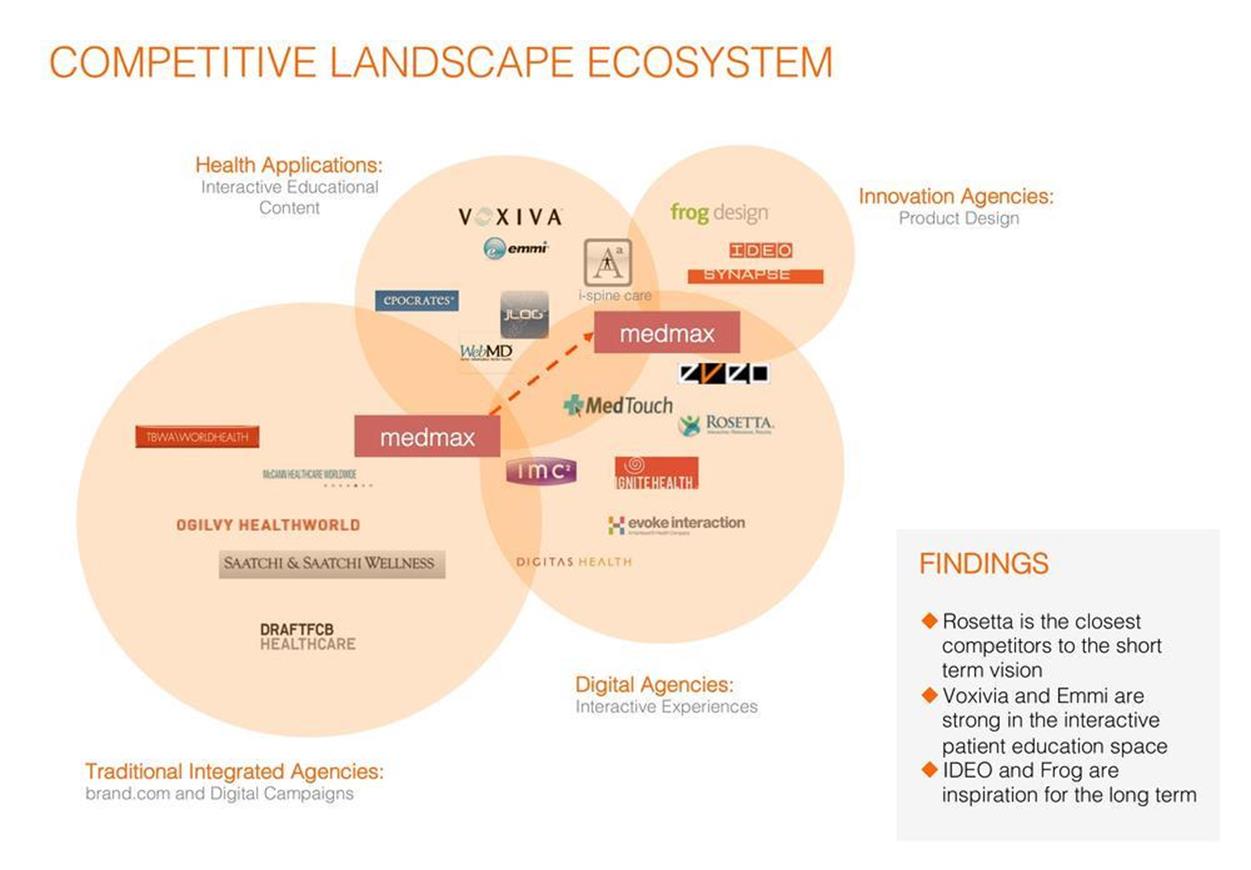

I’m a very detail-oriented person. I have to understand the whole macro view of what else is happening in the market. So, researching the marketplace is always the first thing I do. I want to figure out who the user/target customer is, what types of products that they are using to solve similar problems. I look at every angle of competition. Sometimes, it’s very predictable and sometimes it’s totally outside of the industry that you expect that you are competing in. I like to understand where they’re heading and how they created their UX. I want to understand their design strategy with the product and what it means for what we are trying to accomplish. Being able to share these details with my partners and team helps everyone to be well informed and make better decisions together.

Something I almost always do in every project is a simple ecosystem map (see Figure 10-7) that shows who all the players are, what they have to offer, and why people like them (what features differentiate them). It’s a competitive map but in a framework that is relevant to the product I am working on.

Figure 10-7. Ecosystem map

It’s a good reference tool for everyone on the team. I want everyone to know where we are on the map and where we are going.

9. What is a business case or anecdotal story that you can share that walk us through the steps you have to go through when conducting strategy specifically for an innovative product?

In an agency environment it starts with a brief. The client usually has the basic idea of the product or service it would like to create or at least the problem that it wants to solve. Often it might have an idea for the solution without completely understanding the true source of the problem, and it needs help with really clarifying both the problem space and the opportunity. So in the agency context, we begin by downloading the knowledge from the client, synthesizing what it knows and what the market tells us, and then coming up with a clear destination and a roadmap to get us there.

In the case of a tech startup, things are a little bit more fluid and iterative. The approach is more or less the same, but less time and effort is spent on consensus building across the client’s organization. More time is spent on refining and optimizing. There are less artificial time constraints, but often more resource constraints, so we must be very lean in our thinking.

In my current startup, the vision is clear and set, but the strategy has evolved and continues to evolve. Our initial vision came from us observing a certain kind of behavior that people were exhibiting around the way they were using email where email wasn’t the most efficient solution. We thought something could be done about that. We didn’t immediately know the perfect solution, but we had a very clearly articulated problem. We were not sure if the solution was a different kind of email app, or note-taking app, or even a task-management tool. So, step number one is to clearly identify (or make an educated hypothesis) about the opportunity space, or the problem that you are addressing for the end user. Based on this knowledge, we then form a strategy, a plan of action for the solution. In our case, we began to come up with a few different solutions that we believed were possible alternatives. But we didn’t know for sure until we really began designing, and prototyping. When we understand more or less what we wanted to design, we could do a more focused competitive analysis, looking at other similar products and talking to people who used those products. And based on that knowledge we tweaked our prototypes until we basically ended up with one solid solution. The lesson is that strategy is iterative just like everything else. You come up with a hypothesis, you create a plan, and you move forward until you learn new information, reposition the hypothesis, and adjust the plan. Strategy is a living experience.

10. What are important skills or mindsets for a strategist to have? Or what makes you good at your job?

What makes me good at my job is a combination of high-level thinking and focus on details and logistics simultaneously. You have to do a lot of “homework” before coming up with a strategy that might be not so exciting. But the way you put it all together into a story that’s both inspiring and practical is where the magic is. It’s not always that easy. You have to have the vision. You have to see the big picture and get excited about the possibilities. But you also have to be able to communicate that to other people so that they can get behind you.

Geoff Katz

Born: St. Louis, Missouri, US

Currently resides: San Francisco, California, US

Education: BA in History from Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

Figure 10-8. Geoff Katz

1. How did you become a strategist and/or get into doing strategy as part of your work?

So, I think the word “strategy” has very different meanings to different people, and you do a great job at boiling it down in the book. For me, helping people cut through the confusion, identify, and prioritize real opportunities is kind of what’s at the heart of the strategy work that I’ve done across a number of different consumer entertainment technology platforms. I’ve been lucky enough to be able to work on what you can call emerging platforms time and time again. There was a moment where the Web and animated GIFs were an emerging platform — that’s where we all started — and if you remember the first websites for McDonald’s or Levi’s from 1995, you’ll know what I mean. The opportunity to try to really figure out what people might like to do, because in a lot of these cases the media hadn’t existed previously, identify the essential components of what a UX could and should be, and then create a blueprint for how a product experience comes to market is what I’ve been focused on over the last 20 years.

My background and training studying the history of ideas was a perfect setup to have a strategy role in my professional life in the sense that you’re learning to constantly evaluate very specific primary sources of information and then using that to inform a bigger-picture story that needs to be original, interesting, and engaging for a particular audience. I started my professional career in advertising, and the task at hand with that was communicating clearly and succinctly in 30-second chunks. I was a television-commercial producer before the Internet, so when I moved from the big ad agency world to the unfathomable depths of the Internet at Organic in 1995, I was always working to pull things into focus for our clients and lead the design and engineering teams toward goals that were able to be understood quickly and clearly actionable.

2. What does UX strategy mean to you? Is it a bogus job title?

Having worked across a range of direct-to-consumer products and B2B products, UX strategy is really an essential component of product definition. Today, there are entire disciplines that make up parts of what you or I would have normally done on any given day on and interactive media design and development project. For people getting started in UX and product design today, the opportunity to go through academic programs as an undergraduate, postgraduate, or through professional training and get deep experience with every part of the interactive product design and development process is important. That broad background is what differentiates a UX designer from a UX strategist.

Strategists needs to have a higher-level perspective and a certain confidence about where the world is headed in order to be successful. I think it really takes will to help people, to pull emerging opportunities into focus and to define them in a way that is actionable by a team of engineers. I’ve heard time and time again over my career from engineers that they “just” want to be told what to build. That doesn’t mean that they’re not creative people. It’s that for them, without an extremely detailed level of specificity, software doesn’t just “happen.” Making the strategic effort to really tease out that detail and lead teams to where the world will be in 6 or 8 or 12 months and deliver a product that fits with a market at that time, is the fundamental work of a UX strategist.

I don’t think the title is bogus. It is a new title that recognizes that there needs to be someone at every company focused like a laser on supporting the business objectives of the company from the point of view of design. By identifying product opportunities based on the evolution of technology and user behavior and driving innovation through product design you can effectively deliver a product that is fundamentally better than anything they’ve seen or used before and achieve product/market fit that will help your business scale. UX strategy spans across a number of previously siloed disciplines. In fact, there’s evidence that leads me to believe that it’s growing as a new discipline. There was a moment where UX design in general was seen as a BS title. Clients at some of the interactive design agencies I’ve worked for just wanted to see pixels on a page, and the way that design behaved, the way that design made an experience easier or harder for a user, and how that contributed to brand, really was an afterthought. As the world became a little more sophisticated about the UX of interacting with screens and put the user at the center of the product design process, UX as a distinct discipline emerged and has become a fundamental part of interactive product development. I think that the UX strategist is now emerging as an important role because it bridges what could be seen as really disparate and distinct silos, design, experience, and business, and that’s why I don’t think it’s BS. I think it’s incredibly important.

3. How did you learn about business strategy?

On the streets. I don’t have a master’s or bachelor’s degree in design or business. When I was doing my formal liberal arts education, most of my classmates were aspiring to be lawyers, not MBAs. Art and design were something you did as personal expression, not as business, and the state-of-the-art technology was color Xerox. The accepted goal after four years of studying history was to take the LSATs and go to law school. An MBA was not even on my radar as an option at that time. So I moved to San Francisco, joined a band, and started making our posters. I saw the Macintosh computer having an impact on the way that print production was evolving and, taking my cues from how quickly that technology was evolving, I focused on using computers to do design. It was only in the early ‘90s that computers began to become a part of the creative process. Being someone who could work side by side with traditional graphic designers, art directors, commercial TV producers, and collaboratively work to bring computers into design and advertising as new tools that could unlock new business opportunities is really been something that has been fundamental to my career, since those earliest days. I think for a long time, like back in 1994 and 1995, the idea that not only the web would be ubiquitous, but it would be the primary business channels was quite hard for people to grasp. The web browser put a graphical face on the Internet that which was at the time less useful than interactive services like CompuServe (forums, email), AOL (dial-up walled garden of content), and Prodigy (ISP).

I was actually at a meeting at Netscape the day that they went public. I remember seeing someone wheeling a pallet of champagne down the hallway and knew that we were witnessing the beginning of a new world. And at the time, the Netscape guys would talk to us about how browsers would evolve (remember “frames”?) and where the Internet was headed. They were telling us that by 1997 the Internet would be a true direct-to-consumer business channel. It’s hard to think back to what the Internet was in 1995, but it was anything but a business channel. It was a big experiment. It was text and hyperlinks and bad graphics. Students at UC Berkeley that I interviewed in 1995 for a project for CKS Partners about how people were using the Internet couldn’t conceive of it ever being commercialized or using the Net to buy products. Jodi.org wasn’t going to have a billion dollar exit. But big companies like McDonald’s, Levi’s, MTV, and Disney did begin using the Internet as part of a new business strategy — first as an experiment, then as a new marketing channel, and ultimately the Web and Internet-connected products have become one of the most significant forms of direct-to-consumer and B2B business communication and as a source of revenues. Especially the entertainment business, starting with music and now TV everywhere, film distribution, UGC on YouTube, and social apps: you get the drill. Business (not art) is what made the Web more than just a fad or a technology experiment. Ultimately — I hate to say it — if these efforts and these one-time experiments didn’t ultimately contribute to the bottom line, they wouldn’t exist. I have been lucky enough to work for some of the biggest companies in the world to be able to spend their money, or their investor’s money, to prove out what works and what doesn’t work in interactive media. I think once every five years or so, something crazy like Facebook comes along that has its own center of gravity and kind of pulls everybody forward. But those other four years and 364 days, we are putting one foot in front of the other, just inching out over the known horizon and trying to turn fundamental technology into killer products and build sustainable businesses.

A lot of what we do as UX strategists is informed by the work that other people are doing in parallel at a particular time. Rarely in the history of businesses has there been such a fluid landscape ahead, and the pace of change is quickening. We’re still in the first couple of decades on how a globally connected media world really will affect the future of everything, not just what we view and see on our phones but the way that the world works in the future. Even this interview that we’re doing right now over Skype would have been unfathomable 15 or 20 years ago. In How We Got to Now, Steven Johnson does a great job of explaining how small, incremental technology innovations and experiments, often performed by people who are never recognized for their contributions, can ultimately change the world for the better in ways they could have never foreseen. I’d like to think that the contributions we make as UX strategists are similar contributions that will ultimately make the world a better place.

Working in the entertainment and media business, looking at the evolution of platforms from PCs to music players, to smartphones, tablets, game consoles, new connected devices like the HoloLens or Oculus Rift, new devices like the Amazon Fire TV Stick that turn your TV screen into a whole new entertainment experience, it’s a constant challenge to look out a little bit ahead of where the world is today and imagine what it’s going to be like in the next few years. Just this week, Chase Carey, COO of 21st Century Fox, said in his earnings call that “the business you see today will not be the business you see in a few years.” That said, the seeds of what’s going to become normal human behavior really were there from the very beginning of the Internet. In 1994, at the “Information Superhighway Summit” in Los Angeles, Al Gore talked about the 500 Channel Universe and the Internet and that’s the world we live in today — just add a few more zeros. Countless experiments need to happen before new technology enabled experiences become part of day-to-day behavior, and as a UX strategist, it’s fun to be part of that effort. So basically, I learned business strategy from participating in all of these cross-platform product initiatives and seeing what did work and did not work with users.

4. Do you think it’s helpful for UX designers who are aspiring strategists to get an MBA or have a business degree?

I think it’s important for UX designers to be grounded in the reality of what it takes to be a successful company. I don’t know if that really requires a business degree. I’ve worked with companies with thousands of employees and with companies with eight employees, and I think there’s a certain value in everyone understanding the reality involved with everybody getting a paycheck every couple of weeks. That’s something that really needs to be ingrained in people’s mental models of why they go to work and what they do every day. There’s a component of living and working in Silicon Valley in the last 20 years that kind of creates a false impression that there’s an unlimited amount of money and that the next funding round will just get you through the next stretch of time until you can figure out exactly what your product needs to be and what market it serves. But, I don’t think everybody’s that lucky in the big, wide world. At the end of the day, you try to create a great product that people love to use, and that’s a huge milestone, but it’s not necessarily a business yet. Even companies like Facebook and Twitter that have built great user experiences and wildly successful products and take their companies public are under incredible pressure every quarter to meet those projected numbers, so well-designed and loved products aren’t enough — you need to make money, and the more of it, the better. So, I don’t think that it’s possible to think about UX, product design, and UX strategy separate from the business realities of the world. I do think it’s a requirement for a strategist to be grounded in basic understanding of how a business really works and scales.

5. What types of products have you done the strategy for that were the most exciting or fun to work on?

I’ve always had the opportunity to work on consumer-focused media and entertainment businesses, so for a kid growing up watching TV it’s all fun. For me, from day one of the consumer Internet, we saw it as something that would be this kind of connected, unlimited, TV distribution platform. But, it wasn’t really until consumer broadband began to happen at the end of the 1990s, when I was at Excite@Home, and moving into the 2000s, as people became familiar with how digital video would truly be under total user control on DVD and on DVRs like Microsoft’s Ultimate TV and TiVo, that the dream became a daily reality for most of us. Now, with ubiquitous broadband, digital video, and a certain level of habituation around controlling media on connected devices, we finally have reached the world that I hoped we would at the very beginning of the Internet. What’s been exciting and fun for me is always having the opportunity to create the first examples of what products on these new emerging platforms could be like. I love to explore how these technologies work and think about how they will make the entertainment experience better and more engaging as media moves to new platforms. There have been times that concepts and products I’ve worked on have washed up on the rocks of history, and there are other times they’ve proven to be widely adopted. I think they’ve all been fundamental stepping-stones to the way people use and interact with media entertainment today.

6. What are the some challenges of conducting strategy in different work environments (for example, startups versus agencies versus enterprises)?

I’ve had the opportunity to work at both big product companies like Excite@Home, DIRECTV, and TiVo, and also at interactive design agencies. For example, in the mid-2000s I was lucky enough to work for a while at Kevin Farnham’s company Method, the brand experience design firm in San Francisco, and had the opportunity to start a media entertainment practice there that had both big entertainment product and service clients like Microsoft and Showtime Networks, and startups like Boxee.

For me, the easiest way to describe the challenges of conducting strategy in different work environments is that when you’re inside of a product company, you’re basically living in a world with blinders on; your focus is 100 percent on your product and the market segment that you’re competing in. Day-to-day focus is on the products that are currently in development, and all your energy goes into pushing that product development effort forward across all these different constituencies inside a company. When I was at DIRECTV, for example, they were in the business of putting satellites in space and sending video to set-top boxes in living rooms. So, the idea that we were going to create new “advanced services” that were new forms of data, and that you were going to bind that data to the satellite signal and download it to drive new user experiences, was met with a level of fear by the guys who built their careers as Hughes Corporation engineers. It was a new way to think about exploiting the platform they had developed, and their culture was one of absolutely avoiding risk. “You’re going to download something that’s going to turn millions of set-top boxes into bricks?” And the answer was, “Yes!” This kind of calculated risk-taking injected into a risk-averse culture at a big company is a big challenge, and it’s not a surprise that it took a change in control — News Corp. bought the company and changed the culture — to create an environment where innovation could continue to flourish. The siloed nature of big corporate structures doesn’t make taking risks a big part of the day-to-day. In fact, they’re all there to mitigate risk and focus on maximizing profits from where the business is today. This is the innovator’s dilemma, and as UX strategists, we deal with that in one way or the other every day.

When I worked at an agency, the challenge was a little bit different. You have very broad perspective. You have visibility into what a lot of companies in a broad range of industry segments are thinking about doing — and they need your help to actually get it done. The challenge in an agency environment is really trying to find a champion or advocate inside of your customer’s company that can fight that good fight, given the things that are structurally inherent in corporations that I mentioned before. The tough part about that, though, is you do your work, complete your deliverable, and you walk away. Then, you work on the next project. The beautiful part of agency work is that you don’t live inside of those client corporate cultures forever. The downside is that often those projects never see the light of day in the real world.

7. Have you ever conducted any form of experiments on your product or UX strategy, whether it be trying to get market validation on a value proposition or testing prototypes on target customers? How do you get closer to the truth while you are conducting strategy?