UX Strategy: How to Devise Innovative Digital Products That People Want (2015)

Chapter 8. Conducting Guerrilla User Research

Take a chance and step outside.

Lose some sleep and say you tried.

Meet frustration face to face.

A point of view creates more waves.

— JOY DIVISION (1979)

BY RUNNING SMALL, STRUCTURED EXPERIMENTS, THIS QUALITATIVE fieldwork will help you to immediately validate assumptions about the value proposition and innovative key experience from the users themselves. In this chapter, you will focus on harvesting actionable takeaways from your potential customer segment through guerrilla user research. You will use the prototype from Chapter 7 to get closer to the truth with an open heart and mind to really hear what your potential customers feel and think about your product’s core experience. This chapter focuses on Tenet 3, Validated User Research (Figure 8-1), and makes use of the UX Strategy Toolkit.

Figure 8-1. Tenet 3: Validated User Research

Guerrilla User Research: Operation Silver Lake Café

On September 23, 2013, an unarmed team of UX vigilantes launched an organized attack on the value proposition of the software engineer I introduced in Chapter 1. The treatment center operation lasted 8 hours and involved 10 participants in two hipster café locations in Silver Lake, California. The entire team of vigilantes (team lead, UX researcher, and event coordinator) and interview participants walked away unscathed. Neither café location was compromised, and all interviews were conducted without major incident. However, the client left the scene emotionally exhausted because the result from the research falsified his hypothesis that his desired customer segment — everybody — would be willing to pay for this solution, which left his business model in shambles.

Here is how the events played out:

1:10 p.m.

A UX researcher arrives at Café Location One. She buys a coffee and leaves a large tip. She then walks to the upper level to find an isolated area, out of view from café workers. The area has about six square tables. All the seats are taken, so she waits for a table to clear.

1:30 p.m.

A table clears with two seats; the UX researcher grabs the table and throws her extra jacket over the one seat. She takes out her laptop to test the WiFi connection and AC power outlets. While she sets up, Jaime (team lead) and the client (the software engineer) enter the café. They buy coffee, leave a large tip, and make their way upstairs. They make eye contact with the UX researcher and scan the area for a possible primary interview table for three.

1:45 p.m.

A table for three clears that is near an AC outlet and also has a view of the staircase. Jaime sits at the seat facing the stairs. The client sits opposite from her. Jaime texts the event coordinator: The interview location is ready. The event coordinator takes his position in front of the café and pulls out his clipboard to look official. His job is to catch participants before they enter the café.

1:55 p.m.

Participant One shows up at the cafe. The event coordinator greets him at the door. The coordinator walks Participant One into the café and up the stairs to the primary interview table. He introduces him to the team lead and client. Before he leaves, the event coordinator takes Participant One’s order for coffee.

2:05 p.m.

Participant Two shows up five minutes late. The event coordinator greets her at the door. He walks her upstairs to the secondary interview table with the UX researcher, who greets her in a respectful and professional manner. He then takes her order for coffee and goes downstairs to buy the beverages; he leaves a large tip. The event coordinator returns upstairs with the beverage orders for both participants. It’s at this time that he also gives them their cash payments. While the interviews commence, he then goes back outside and waits for the next set of participants to arrive.

2:10 p.m. to 2:45 p.m.

The team lead and UX researcher conduct 30-minute interviews and wrap them up on time (Figure 8-2). The client listens to the interviews and takes notes in real time that are saved in the cloud for the team to view. When concluded, the team lead and UX researcher quickly discuss if any changes need to be made to the interview questions. They make those edits and then text the event coordinator to bring up the next participants.

Figure 8-2. Guerrilla research interview in session at Café Location One: team lead on left; participant faces the wall; client on the right

2:55 p.m to 4:59 p.m.

During this block of time, Participant Three arrives. Participant Four ends up being a no show, and Participants Five and Six arrive as planned. The event coordinator greets each participant at the door, takes them upstairs to the appropriate interview table, takes their drink order, delivers it, and pays them. The team lead and UX researcher conduct and conclude the remaining interviews on time while the client continues to observe and take notes.

4:45 p.m.

After the last scheduled participant arrives, the event coordinator heads down to Sunset Boulevard to Café Location Two. He orders a sandwich and beverage and then finds a table near an AC adaptor to prepare the next location.

5:00 p.m.

The interviews at Café Location One wrap up after three hours. A total of five participants have been interviewed. The UX researcher, team lead, and the client discuss their findings, capture their insights, and tweak the interview questions for the second set of participants at Café Location Two. The UX researcher goes home; she’s not needed for any more interviews. Jaime and the client head down the block to the second location. They meet the event coordinator and order dinner. By 5:20 p.m., the event coordinator takes his position at the door with his clipboard.

5:30 p.m.

Participant Seven arrives. The event coordinator greets him at the door. He takes the participant to the table.

6:00 p.m.

Participant Eight arrives 30 minutes early through a back door in the café. She heads directly to the interview table and interrupts the interview in session. Jaime takes Participant Eight over to the event coordinator who deftly handles the situation. Jaime finishes up the interrupted interview.

6:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m.

Two more interviews are conducted without issue. One participant who was intentionally double-booked at the halfway point shows up, is paid, and is excused after 30 minutes.

8:30 p.m.

The interviews at Café Location Two wrap up after three hours. A total of three more participants have been interviewed at this location.

9:00 p.m.

The client, Jaime, and event coordinator discuss their findings and capture their insights. The debriefing session concludes, and all parties go home.

After a long day, a week of planning, and a $5,000 research budget, we didn’t even need to look at the notes afterward or analyze what we found. It was clear the participants consistently admired and applauded the solution prototype. They loved the value innovation and key experiences demonstrated through the UX in the prototype. But, the stakeholder knew in his heart that he had a major pivot on his hands. Even though the customers were enthusiastic about the solution, they continually invalidated his business model — channels, revenue stream, and cost structure. (See the business model canvas in Chapter 2.) Without it, his product wasn’t sustainable. He had to go back to the drawing board, pivot, or make a tough choice about whether to continue or not.

LESSONS LEARNED

§ When you put key stakeholders in front of a real customer, they will learn the good or bad news sooner rather than later, directly from the source.

§ An organized, well-coordinated, and mobile team effort is essential to successful field research.

§ To get validated learnings, you don’t need to invest in an expensive or time-consuming endeavor.

User Research versus Guerrilla User Research

The purpose of conducting user research is to understand the needs and goals of your target audience in order to inform the value proposition of the product. There are many traditional techniques for understanding users’ perceptions including card-sorting, contextual inquiries, focus groups, and surveys. There are hundreds of books that you can buy to learn user-research techniques. The two recent ones that I like are UX for Lean Startups by Laura Klein[56] and The User Experience Team of One by Leah Buley.[57]

User research usually involves usability testing and/or ethnographic research. Each has advantages and disadvantages, and it’s important to know the difference so that you can decide what kind of research is best for your product and process.

Usability testing focuses on whether your products work by discovering how people use the product in real time. Data points tested in a usability study include the following:

§ Does the user perform the required tasks using the interface?

§ How many clicks does it take for users to perform them?

§ How long does it take for the user to figure out your product?

The answers to these kinds of questions can validate whether your product’s calls to action are positioned correctly, whether the user can find important information, or if the nomenclature of the navigation is clear. Traditionally, usability testing is conducted in special usability labs with two-way mirrors or on the premises of large corporations. Nowadays, it can be conducted remotely by using online services (such as Usertesting.com) that provide quick, reasonably priced screencast videos that record how people use your product or prototype while speaking their thoughts. However, usability testing generally is to interaction design what quality control is to physical product design. This means that it’s typically conducted after the product is completed but before it’s released to the general public.

In contrast, ethnographic research — the study of people in their natural environment — is all about getting to the deep, dark places much like the qualitative personas Alan Cooper advocated in Chapter 3. To get an idea of how in-depth it can be, let’s look at one of my heroes, anthropologist Dr. Genevieve Bell from Intel. In 2005, I saw her give an inspiring keynote speech about a project she conducted in Asia to learn how people use technology. The research was meant to gather insights from developing countries to inform Intel on future chip designs. Over two years, Dr. Bell visited hundreds of households in 19 cities in 7 countries. She described one story about how she tracked down a woman in a remote village. Even though the woman didn’t have water or electricity or even a computer, she still regularly corresponded by email with her son who was away at college. So how did that happen? The woman walked dozens of miles to a family’s home, and the family helped her with all email transmissions. The woman never used the computer at all!

That kind of user research takes some hardcore contextual inquiry. And although I admire Dr. Bell, her intense fieldwork, and her comprehensive and thought-provoking analysis, most of us don’t work for Intel or have the time and money to spend on that kind of research. When I try to estimate the expenses myself — more than 200,000 air miles traveled, hotels, guides, per diem, 19 field notebooks[58] — my mind boggles. Unless you’re working for a big-budget client, large enterprise, or research division with long-term initiatives for product strategy, it’s probably more likely that you’re dealing with a research-averse stakeholder who is in a big rush to “get something out there.” In this case, convincing him to perform any user research whatsoever can be a challenge. Instead, you need to have faster ways of conducting qualitative user research that will deliver immediate feedback with testing budgets closer to $5,000, rather than $500,000. So, what do you do?

The answer is guerrilla user research, which can be thought of as a nonlethal form of guerrilla warfare. Guerrilla warfare is a strategic form of confronting the enemy using a small mobile force to perform ambushes and hit-and-run tactics. Who is “the enemy,” you might wonder? The main enemies for your team are probably time, money, and resources, because if you run out of them, you might never know if you’ve actually created an innovative but sustainable digital product. For clients with little time or no budgets, traditional user research such as ethnographic studies would take too much time, and usability testing just isn’t relevant to help determine if your value proposition is on target or your key user experiences provide value innovation. That’s where guerrilla user research comes in — it’s cost-effective and the mobile tactics should help you to validate the following quickly:

§ Are you targeting the correct customer segment?

§ Are you solving a common pain point the customer has?

§ Is the solution you are proposing (demonstrated in the prototype of key experiences) something they would seriously consider using?

§ Would they pay for the product, and, if not, what are the other potential revenue models?

§ Does the business model work?

Even clients with fat budgets should consider performing guerrilla-style research. That’s because doing this form of “lean” research is not just about saving money, it’s about saving valuable time. The tech industry moves at a rapid pace and innovation is a moving target. As I’ve talked about in many chapters, your window of opportunity to do something unique is either closing or shifting. Guerrilla user research assures you that your team’s “operation” will deliver immediate, useful, and pointed knowledge.

GUERRILLA WARFARE: A SPOTLIGHT ON JUANA GALÁN

One of the most famous female guerrilla fighters of all time was Juana Galán (see Figure 8-3). She became known in 1808 during the Peninsular War when Napoleon Bonaparte’s Grande Armée attacked Spain.[59] His formidable army consisted of hundreds of thousands of well-drilled and disciplined professional soldiers. To defend her home, Juana Galán organized the women in her village to fight back. She led them through highly improvisational tactics such as pouring boiling oil on roads and throwing scalding water out of windows against the French soldiers. These mobile combatants not only saved their own village but also played a part in the French army’s decision to abandon the entire province of La Mancha.

Figure 8-3. Portrait of the Spanish heroine guerrilla fighter Juana Galán (1787–1812). Licensed under Creative Commons

The Three Main Phases of Guerrilla User Research

Guerrilla user research is different from traditional user research methods because it is fast, is lean, aligns the team vision, and provides immediate transparency with the stakeholders. But it requires a lot of coordination. Unlike a sterile research room with recording devices, you can’t control your environment in the wild. So, your team needs to think through every step in the process and have several back-up plans in place. Lives might not be at stake, but cost and time must be contained!

Let’s begin with a high-level review of the three phases to understand the basic breakdown of time and expense involved. Then, I will explain each phase in detail using the treatment center operation as the case study.

Planning phase (one to two weeks depending on team size and number of participants)

The planning phase is the most complicated of all three phases because it involves everything from finalizing your solution prototype to scheduling the participants. Everything must be thought through, timed, and rehearsed. Everyone involved must know their respective roles and where to stand or sit. As in a guerrilla warfare action, you need to get in, do the thing, and then get out quickly without being “captured” (in other words, thrown out by the café owners).

The five steps that I will teach you to ensure a successful planning phase include the following:

Step 1: Determining the objectives of the research study. Define which aspects of the value proposition and UX are being examined.

Step 2: Preparing the questions to be asked that will get us validating. Then, rehearse the entire interview along with giving the prototype demonstration.

Step 3: Scouting out the venue(s) and mapping out logistics.

Step 4: Advertising for participants.

Step 5: Screening the participants and scheduling time slots.

Interview phase (one day)

The interview phase can be the most nerve-wracking and exhilarating of all three phases, because you must prep the location, coordinate the sessions, and conduct the interviews.

The interview phase involves:

§ Prepping the venue

§ Participant payments, café etiquette, and tipping

§ Conducting the interviews

§ Taking succinct notes

Analysis phase (two to four hours)

The analysis phase is the least complicated of the three phases but is still essential. Don’t get sloppy on this phase, because you need to aggregate the data captured during the interviews, debrief team members who sat in on the interviews, get the client’s feedback if the clients was present, synthesize all of these inputs quickly, and ultimately decide if the interviews were effective in getting the right kind of evidence. The last step is making decisions on the best way to move forward based on your analysis.

Planning Phase (One to Two Weeks)

Step 1: Determine the objectives

In this first phase, you need to establish the objectives of the research study and define which aspects of the value proposition and UX was being examined.

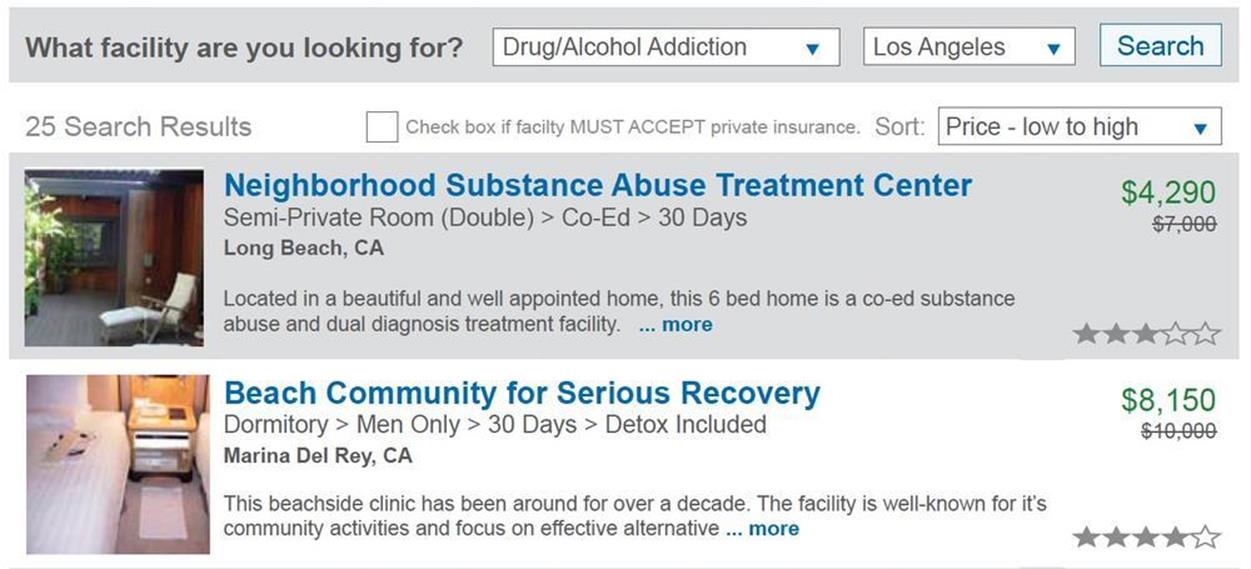

Ask yourself, “What is the most important thing I need to learn to determine if this product really has any purpose, marketability, and viability?” What this means is that you need to ask what is the riskiest assumption(s) still on the table at this point in your process. In the case of the software engineer, the value proposition was still up in the air. If I use the formula introduced in Chapter 3, I can tell you that the value proposition before the guerrilla user research was basically Hotels.com for people seeking treatment for their loved ones. The software engineer’s interface provided a matching system similar to Hotels.com, in which users enter a price that they want to pay. The system then offers matches in the specified price range. As in Hotels.com, the name of the rehabilitation center would be withheld until after the user booked it. A big concern was that my team didn’t know if this reverse-auction business model was desirable for that user segment.

Because the business model was innately tied to the UX, this uncertainty paralyzed our ability to make any other decisions about the product. We could not move forward until we could determine the success or failure of the value proposition. This also meant that we had to decide as a team along with the client how many times we would hear the word no before heading back to the drawing table, versus how many times we would need to hear yes before moving forward. At the end of the entire operation, what would be our success criteria? That of course depended very much on the feedback from the participants we would interview.

Step 2: Preparing the interview questions

Chapter 5 discusses the distinction between quantitative and qualitative data points via a Starbucks latte (16 ounces and 90 degrees Fahrenheit versus comforting and yummy). There is also a distinction between quantitative and qualitative user research that goes beyond data points, because often we will collect both in either type. Quantitative user research generally relies on a large sample size of users. More users means more numbers. In contrast, qualitative user research will rely on a smaller selection of customers — quality over quantity. This is the main difference, and qualitative user research is the kind of research your team will conduct.

In guerrilla user research, your goal is not to place the prototype in front of 1,000 users in one day. Instead, it is to interact with 5 to 10 handpicked users to gain intensive and pointed insights. The Nielsen Norman Group believes that testing up to 5 users in a usability study is enough people before you begin to hear the same things back over and over again.[60] If you show your product to 10 users and discover that none of them likes the idea, you might have your baseline for whether the product is a success or failure. However, if you want to keep pursuing your value innovation, you need to learn information beyond the user’s like or dislike. You need to persist and discover exactly why, how, and what you can change to make the product better.

Remember, these are not usability tests in which you just observe how the user accomplishes the task with the actual product. These are demonstrations (and not necessarily clickable) that are meant to help the participant visualize the future product clearly enough to give useful feedback on whether they can achieve their goals. You will guide the user through a key experience, and the feedback you receive will predominantly be verbal, real, raw, and in your face.

To get that kind of qualitative response, you need to really think about your interview questions. The right kind of open-ended and follow-up questions can lead to discovering opportunities for value creation you might not have previously considered.

I recommend creating your interview around two great approaches: the problem interview, which you learned about in Chapter 3, and the solution interview, which comes by way of lean guru Ash Maurya.[61] You must carefully construct all questions; they should relate to your product and your expected UX. They shouldn’t lead the participant. The questions you ask also need to be flexible enough to be easily rephrased for each participant’s personal situation. For example, in the treatment center operation, some participants booked themselves into rehabilitation, whereas others booked a loved one.

Here is the general structure that I like to use when building my interview questions. You can access a copy of this format in one of the templates in the UX Strategy Toolkit online. You can also use it to capture your questions online. Share them with your team. Discuss them. Brainstorm about them. Really look at each of them to create the best interview possible.

Set up, recap/verify screener input (three minutes)

Before the participants come to the interview, you need to prescreen them through a phone call or other means, which I’ll discuss in Step 5 of Phase 1. However, when they arrive onsite, you want to kick off the face-to-face interview by verifying what you already know. These questions also warm the participant up to the questions in the problem interview. To make the participants more comfortable, you might repeat back information you learned when you screened them. You might want to have them expand on any aspects that will help you understand their experience.

Here are some of the setup questions that my team asked on the treatment center operation:

§ Can you tell us how many times you have booked your loved one into a rehabilitation center?

§ How long was each stay and did the facility offer you discounts to prolong the stay?

§ How did you find out about individual rehabilitation centers (word-of-mouth recommendation, the Internet, a list provided by a specialist, and so on)?

§ If you used the Internet, how did you find the facilities (for instance, Google), and which sites did you use for finding them and learning about the specific details?

Notice how the questions would seem nonintrusive to the participants. They aren’t shocked by them, because they know (based on the advertisement and screener questions) that that’s why they’re here. However, the questions have a second purpose, and that is to set up the context for the next part of the operation: the problem interview.

Problem interview (10 minutes)

The problem interview is set up similarly to the problem interview described in Chapter 3. The difference is that you are probably going to ask more questions and in greater detail. You want to get deeper insights about the problem, too. In these questions, ask the participants how they solved the problem in the past. Try to fully understand what their experience is like. Have them recite the timeline of problem-solving events they undertake in a linear format.

During the problem interview portion of the treatment center guerrilla user research, my team focused on payment. Who paid cash for a treatment center as opposed to using Medicare? Here are some more examples we asked in this line of questioning:

§ For those rehabilitation centers for which you paid yourself, was the process different in terms of your options for making a selection?

§ Did the center negotiate the price with you? Do you feel you received fair value for what you paid? What do you think makes the cost of the facility worth the price?

§ Do you remember how long in terms of time from when you decided upon the treatment center and the patient actually went in? (Prompt: What is urgent? How long did the selection process take?)

§ Was there anything specific you remember that was really great or really horrible about the process of finding the treatment center?

In total, we prepared 10 problem questions, and the answers definitely gave us a lot of insight into our participants’ pain points. In addition, the questions also helped get the participants back into the mindset of what it was like to experience those problems. In this way, we could contextually prepare them for the solution interview.

Solution demonstration plus interview (15 minutes)

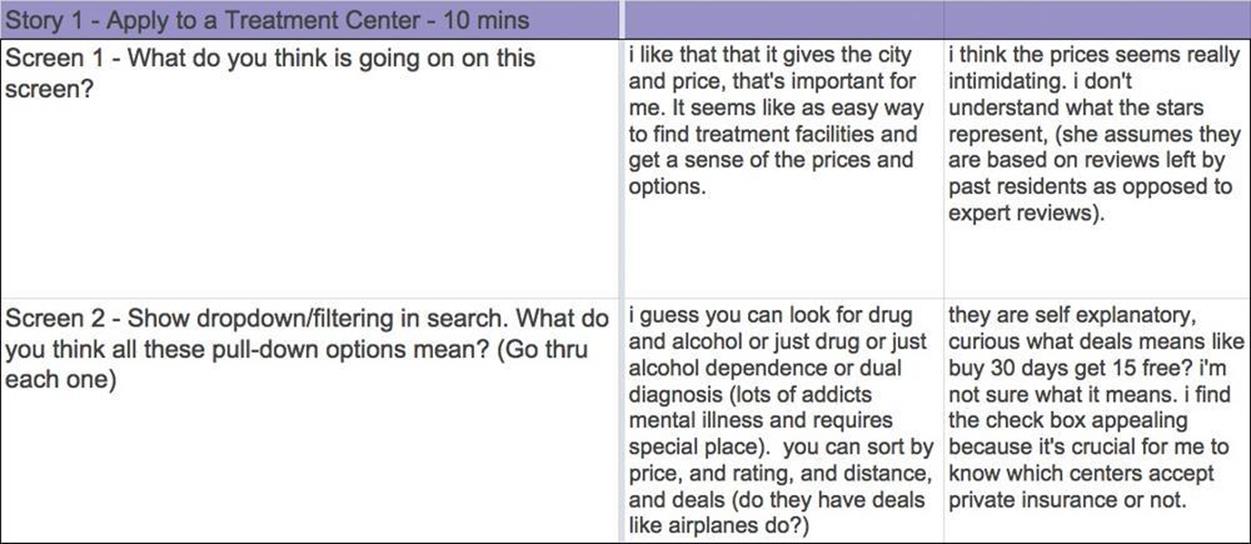

The problem interview sets the stage for the solution interview, in which you reveal your product solution and learn if it solves the customer’s problem. You might need to create several solution concepts and a set of questions for each key experience you need to present. In the case of the treatment center operation, my team presented three solution demonstrations for three key experiences, as shown in Figure 8-4. If you find yourself in that scenario, schedule your time accordingly.

Figure 8-4. Portion of prototype screen from the rehabilitation study

Create solution-interview questions that will encourage participants to think through your solutions and other alternatives; they might have insight into making your product better. Again, don’t create or ask leading questions. Conversely, don’t put participants on the spot by forcing them to brainstorm in front of you. Give them options of familiar mental models that will give the solution prototype context. Be open-ended initially with the questions, and then give enough hints and prompts to validate the solution.

Following are the solution questions for one of the key experiences (see also Figure 8-5). You might also have to contextualize the screen for the users before asking them any questions.

§ Screen 1: What do you think is going on in this screen?

§ Screen 2: What do you think all these pull-down options mean? (Go through each one.)

§ Screen 2: What do you think the ratings are based on?

§ Screen 3: This is the listing page with information about the rehabilitation center. What do you think is going on here?

§ Screen 3: What do you think of the “Apply Now” button? Where do you think it will take you?

§ Screen 3: You might have noticed that we don’t display the treatment centers’ actual names. Would that be an issue for you?

§ Screen 3: Would you be comfortable applying to this facility without contacting it first?

Figure 8-5. Solution demonstration interview questions from the rehabilitation study

Final thoughts (two minutes)

At the conclusion of the interview, be sure to thank the participants by name. Share with them a tidbit of the knowledge you gained from the screener interviews to make it personal, and tell them how much you value their honest feedback. Ask if they might be open for you to follow up with them in the future when you are further along with the product.

Now, your team must rehearse the entire interview using a colleague or friend to play the participant role, asking her the questions and walking her through the prototype demonstration to verify that the questions and solutions make sense.

Step 3: Finding the venue(s) and mapping out team logistics

It’s important that everyone — stakeholders, the product team, and anyone else — take advantage of this opportunity to interact one-on-one with your intended customer. So work with them to ensure that they will attend.

Determine how many people are going to be part of each interview. No matter if you are running multiple interviews simultaneously or one at a time, try always to have one note taker (ideally the client or stakeholder) and one researcher doing the interview. Taking notes and trying to ask questions at the same time consumes valuable time, and it’s important for the interviewer to focus on the participant.

If you plan to schedule multiple interviews, add an event coordinator to your team who can screen participants as they come and go, handle money, and deal with any other issues that might arise. Before the interview dates, your guerrilla user research team should definitely meet and go over all their roles. In the case of the treatment center operation, my team had three preparatory meetings to go over logistics, location, and scheduling.

A big question I always hear is why a café; why not my office, or a lab? Here’s why:

§ You want the participants to feel like this is an informal meeting. They should be comfortable enough to not feel judged, unlike when being watched through a two-way mirror in a lab.

§ The participant will be in a somewhat familiar environment around other people as opposed to a sterile lab or private office in a large building or a coworking space. Your team is the minority; the participant is not.

§ Cafés are free locations! There’s no need to rent a lab or a coworking space. (A hotel lobby can be okay, too, but these locations can be more difficult to access and even harder to find free or nearby parking.)

§ The clients or product stakeholders also can interact with their potential customer in this informal setting. Instead of being separated by a mirror, or surrounded by colleagues, it’s just them, their product, and a person telling them to their face whether they like it or not. It’s hard for any stakeholder to remain on Fantasy Island after that.

Here’s a list of the most important rules for choosing your café:

§ Find and spend some time at a café you like at the exact time of day that you plan to do your study. Ensure that it’s not loud, difficult to find, or insanely busy on the days you want to conduct your interview. I tend to gravitate toward sole-proprietor cafés and away from busy franchises such as Starbucks. Find the café that fits your needs best.

§ Test the WiFi connection. Ensure that there are multiple tables that can comfortably seat three people with nearby AC power outlets.

§ Ensure that the tables are not in line-of-sight of café workers or near an entrance. You want to be tucked out of the way.

§ You’ll need to camp out for three to four hours on interview day so choose a counter-service type café or coffee shop without table service. You’ll want to avoid being disrupted or asked to leave before all interviews are done.

ON NOT USING RECORDING DEVICES

Note-takers are vital components to my interviews because I don’t use recording devices. I capture data in real time and then debrief with the stakeholders immediately afterward. I used to use devices but have since abandoned them for the following reasons:

§ Recording devices make people more self-conscious. Some participants are concerned about sounding stupid, and others fear the recordings could make their way to a more public place like the Internet. In the case of the treatment center project, this was an important issue because the participants were talking about very personal experiences.

§ It’s more efficient and cheaper to bring a person who can type fast notes straight into a spreadsheet or any text document than spending the time transcribing them after the fact.

§ When conducting an interview, it’s better to be in the moment and fully engaged in the conversation as opposed to playing around with recording devices or notes. I pay far more attention to what participants are saying and doing when I know that I won’t have a second chance to listen to the interviews.

§ When you debrief with the stakeholder and your team immediately after the interview, you can instantly make decisions and take action on whether to abandon, refine, or move forward with your solution.

Step 4: Advertising for participants

In certain cases, researchers recommend finding unpaid volunteers because they believe money influences the participants’ answers. Still, you can’t stop people from lying, whether they are paid or not. There is a fine balance between compensating people fairly for their time and extracting the right information from the right people. I recommend compensating participants, because at this point during your strategic endeavor, they are helping us.

Payment amounts also depend on whom you are targeting and how much they value their own time. Seemingly, if you need to speak with busy professionals, you’ll have to pay a lot more then you might to other customer segments. Make your payment high enough to recruit worthwhile participants but low enough to keep your study affordable. Always mention in the advertisement that participants will be paid in cash at the interview. If you’re not sure where to start, try a payment of as little as $20 for 30 minutes. During the initial screening calls with participants, you can probe them to ensure that they have the insights you want so you only end up paying the people who will really help your team.

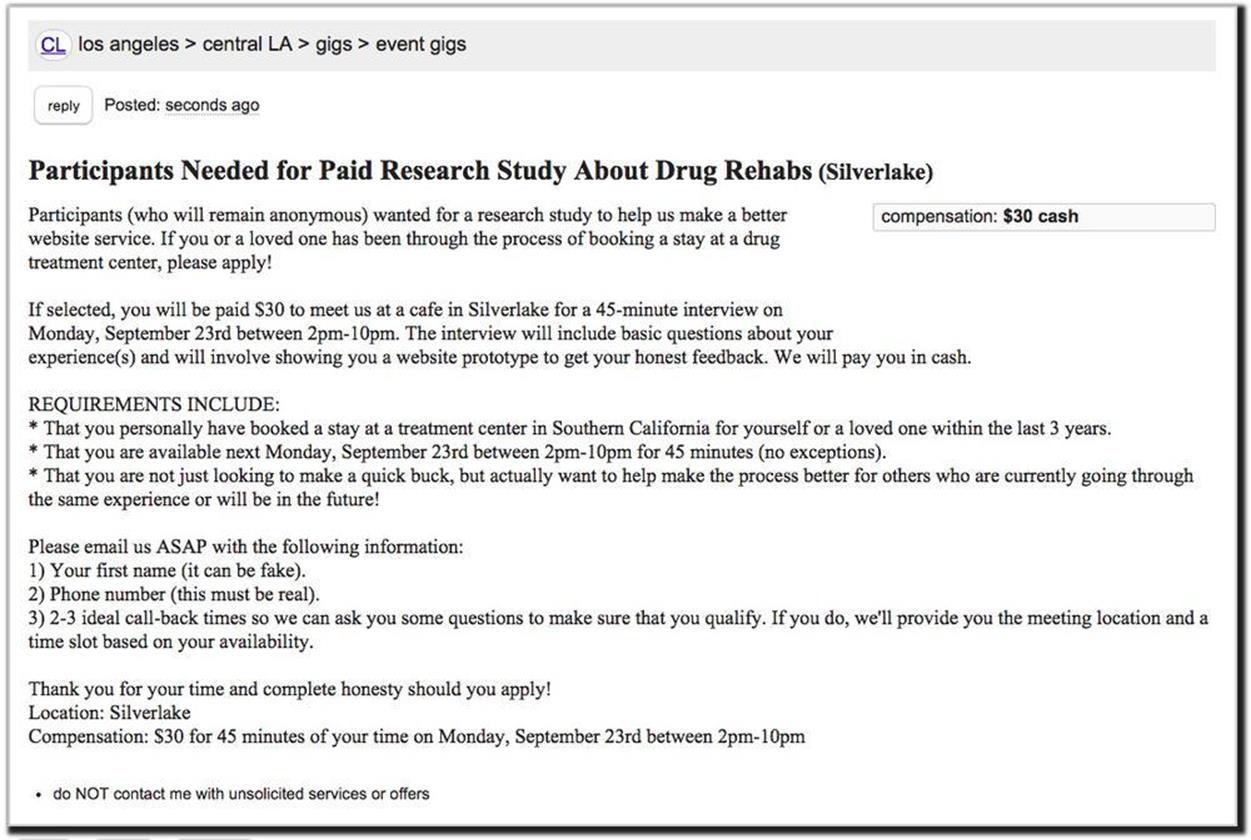

For the treatment center operation, my team initially advertised for participants on Craig’s List. Here are some other ways:

§ Facebook friends (if you have a lot, ask your network for introductions to their friends).

§ LinkedIn Special Interest Groups (post to specific relevant groups).

§ Meetup Groups (attend meet-up groups in your area or post to them).

§ Twitter (use # [hashtags] for casting a wide net or @ profiles for hopefully gaining a retweet among a specific group of followers).

§ Get referrals of friends of friends who fit your customer segment.

§ Canvas an area where there is a high concentration of your target customer segment. For instance, my students at the University of Southern California (USC) were able to recruit participants for their field study by setting up a table in a highly trafficked area on campus and offering free sodas (to those who passed their screener questions) in exchange for making an appointment to be part of the research study.

Just be aware of the implicit bias if you recruit from family and friends.

My team opted for Craig’s List because we assumed it would cast the widest net and get us the fastest responses possible. And it did. Within two days, we had about 75 responses. (I will discuss how to screen through candidates in Step 5 of Phase 1.) However, when we learned after the Silver Lake operation that we needed to target a more affluent customer segment, we opted for another method (see Chapter 9).

When advertising for participants, keep the copy of the advertisement simple. Here is a basic framework of a Craig’s List ad for you to build off of:

§ Title: Paid Research Study: Looking for <customer type> who have experience with <problem type>

§ Body: Market research firm in <city> is looking for <more specific customer type> participants to join an upcoming paid research study.

§ The study is going to be on <day and date of the week> during the hours of <# - #> at a café in the <part of town> area. Please let us know the ideal time that works for you.

§ The study will last for <#> minutes and the compensation is $<##.00>. (optional) The study will not be recorded on audio or video.

§ Please respond with your contact information and the best time to reach you.

§ (optional) Link to survey here:

The framework can change based on the requirements of the study, as is evidenced by the advertisement we used for the treatment center operation shown in Figure 8-6.

Figure 8-6. Craig’s List advertisement for participant recruiting for the treatment center project

No matter the advertisement, make it clear whom you are looking for and why you need their help. The copy should hook your potential customer segment so that they do respond with genuine interest. Date, location, and time will depend on your customer segment. For example, in the treatment center operation, my team needed to schedule interviews on a business day, starting in the late afternoon and running into the evening to accommodate people’s work day. In contrast, Bita and Ena (my former students whom I introduce in Chapter 3) ran their guerrilla user research on a Saturday because that’s when busy brides-to-be tended to be free.

When posting your advertisement on Craig’s List, you have the option of two kinds of ads: free or paid, with some cost variance by city. For example, it’s more expensive to run job ads in San Francisco than Los Angeles, and whether you choose a paid ad will depend on which category you think your customer segment will visit. The two most common sections for running research study ads on Craig’s List Los Angeles are in the “et cetera” and “general labor” sections. If you are not in a hurry and don’t want to pay people, you can try the “volunteer” section, too.

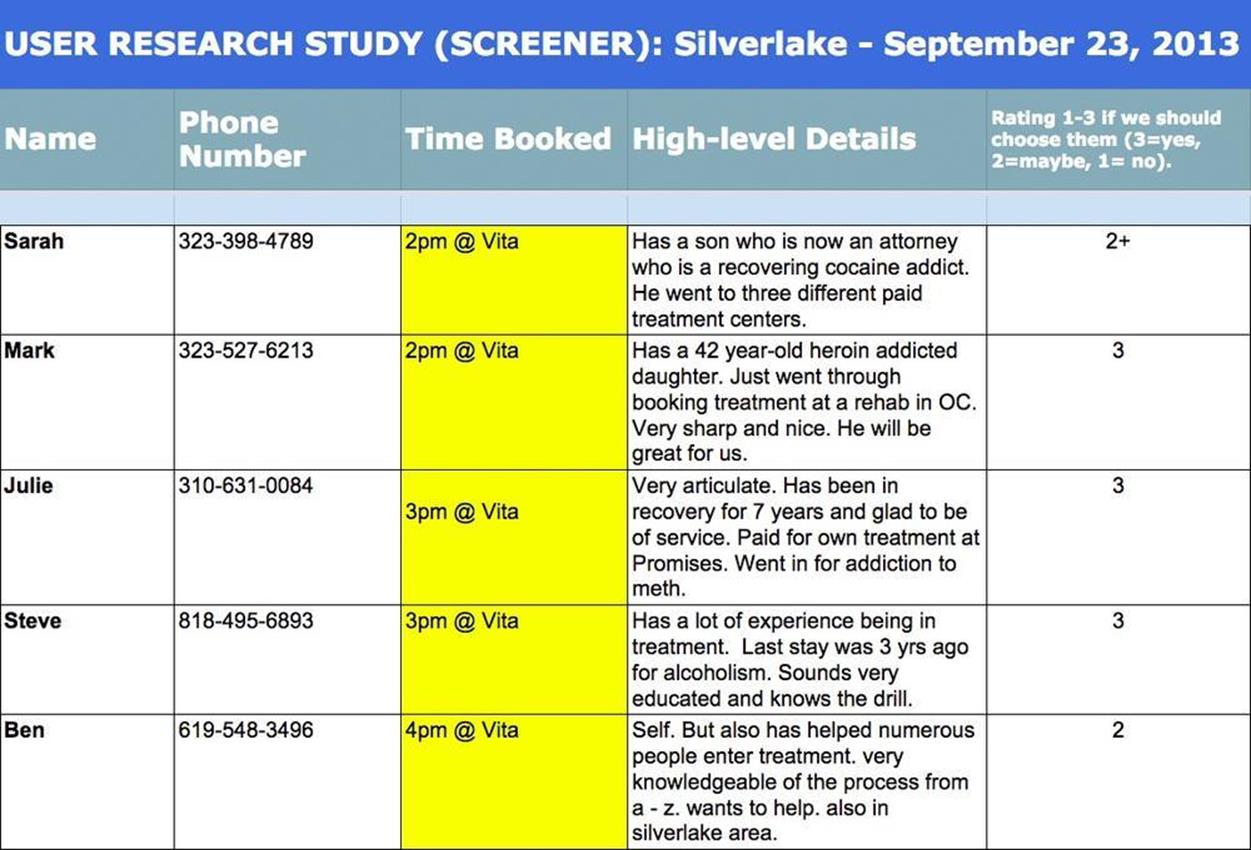

Step 5: Screening participants and scheduling time slots

When you post an advertisement on Craig’s List or elsewhere, you are likely to get responses. But how do you know if the respondents are the people you actually want to interview? This is why screening participants is the most critical part of the planning phase. You must choose participants who match your hypothesized target customers to ascertain if you are validating the correct problem with your solution. This is where thoughtful construction of screening questions comes into play. Look at your provisional persona and think about the critical characteristics needed. Don’t fill your interview with friends or family. By doing so, your study is no longer a “controlled” experiment.

As is discussed in Chapter 3, good screener questions help you to weed-out the wrong people. Yet, whereas you conducted them in person in Chapter 3, you can do it digitally now. You might ask respondents to your advertisement to answer questions that you know are deal breakers. You could send them to a tool such as Survey Monkey or even a Google document. For the treatment center operation, we needed a subject matter expert (SME) to screen our candidates. Whenever a person responded to our ad, that person’s information was captured in a document available to the entire digital team and client. You can see an example of this template in Figure 8-7.

Figure 8-7. Participant screener and schedule

Because the respondent sent her phone number in their initial contact, the SME was able to call her back. He always began the conversation by double-checking the initial information and documenting any changes. He asked for the participant’s name, phone number, and times and dates she’d be available. Then, he asked her the screener questions, such as the following:

§ Were you the person seeking treatment or were you seeking treatment for someone else?

§ Do you mind telling me how much you paid? Where and when did you go? (To confirm it was residential and for how long.)

We needed people who had paid for themselves or loved ones to go to a treatment center, which is why we asked the first question. We needed their experience to be recent (within three years), and we needed to ensure that they could afford paying a certain amount for a rehabilitation, which is why we asked the second question. We also ensured that the ad didn’t reveal that potential participants would be grilled with screener questions as a means to help cut out respondents who just wanted to make money.

After we had this data, the SME gave each participant a rating of 1 (no), 2 (maybe), or 3 (yes). After the SME’s debrief, my team called all the “3” participants to officially schedule them for an interview. Because people’s schedules change, ensure that you try to get them in within 5 to 10 days later.

Interview Phase (One Day)

In this second phase, your team is now executing the planning phase. Everything needs to run like clockwork, like the choreography of a ballet. If something goes wrong, the action cannot stop. Everybody must know their places and how to react and adjust if something unexpected happens. The show must go on.

Prepping the venue

Arrange for each researcher to arrive at the café to find a good table at least 30 minutes before the interviews begin. Before the interview day, you should instruct them on where and how to set up in the quietest area possible; you probably observed where this should be when you found the location. As mentioned previously, it should be out-of-view from café workers and away from major walkways, such as entrances or exits. All devices and laptops should also be charged before arrival. But to be safe, find tables near an AC power outlet, especially if you’re going to be there for a while. Try to avoid sitting by a window or in an outdoor area where there might be glare on the computer or device screen.

There should be one researcher for each table you need. The researchers should each bring a jacket to throw over an extra chair to save it. You don’t want another patron to interrupt an interview or distract the researcher by asking if it’s free. The researcher should do what she can to limit the participant’s visual distraction, too. For example, the researcher can sit facing out toward the main café while the participant sits facing the researcher and only the wall. The table should be clean — food and beverages should be limited. Your team should always have eaten beforehand, and participants should receive at least one beverage of their choice.

Ideally, your team will play your solution prototype on a tablet device because it’s easier to pass to participants, and unlike a laptop screen, it won’t block the participant’s face from you. Ensure that all devices work properly before the interviews begin. Is your demonstration functioning properly on it? Can each device connect to WiFi? If a stakeholder or note-taker joins the researcher, they should sit directly across from each other; this way the participants will sit in between them, providing an optimal view of their reactions and interactions with the demonstration.

Participant compensation, café etiquette, and tipping

Designate a team member to pay the participants upfront. In our Silver Lake scenario, the event coordinator was in charge of this, but it could just as easily be the stakeholder, team lead, or UX researchers. Get the money out of the way early so that the participants don’t wonder about it. Pass it to them in an unsealed envelope as opposed to handing it to them under the table like it’s a drug deal.

Sometimes, participants are concerned about what the compensation means — will this interview be used against them somehow? In the case of the treatment center operation, this was a real concern because we were documenting personal and emotional experiences. Because you’ve screened them beforehand, however, you know that they have a personal interest in helping you; it’s just a matter of reassuring them to participate sincerely. Pay them upfront, and be genuine. Explain that you are paying for their honest feedback. Tell them that you’re not here to pitch the product. This isn’t a “beta-test.” This is just the concept of a new potential product. My team even sometimes says they’re not the people designing it (even though we are) to put some participants at ease.

Because you are using this café or eatery location for free, be cognizant that it is a place of business; don’t be a cheapskate. Spend some money on beverages and food, and most importantly overtip. The team lead or event coordinator should bring a big wad of bills broken into smaller denominations. I have on several occasions put $10 in the tip jar while making eye contact with a barista to ask if it was possible to turn down the music.

Conducting the interviews

Conducting a good interview for gaining worthwhile insights is an art form to be mastered with practice. To learn more, check out a book called Interviewing Users by Steve Portigal.[62] It is an outstanding primer focused specifically on interviewing techniques for conducting user research out in the wild. If you are shy or new to talking to customers, practice with team members and friends beforehand.

Here are my basic guidelines for conducting your guerrilla user research interviews:

§ Always greet people with a warm smile. I typically stand up to shake hands and immediately thank them for coming.

§ Do not begin interviews with small talk. Be professional. You want to quickly build a rapport with them and avoid dwelling on how cool the café is or how difficult it was to find parking.

§ Quickly state the reason why they are there and that you looking to them for their brutal honesty. Then, launch into your setup questions.

§ Stick to the script. Ask additional follow-up questions if needed to probe deeper into specifics about how they currently solve the problem. Find out how, if, and why your solution would work or not work for them.

§ Have the note-taker set his phone as an alarm to keep your pace (typically 15 minutes). The ringer should be on silent so that the phone vibrates to indicate to the researcher at the table that it’s time to move on to the solution portion of the interview, even if there are more questions to go.

§ Ensure that you schedule buffer time between participants in case an interview does go longer than planned or a participant shows up late.

§ At the end, thank the participants for their time and tell them how helpful their insights were.

You also should be able to make slight changes to questions and the solution prototype throughout the day. This is another benefit for your team to conduct, collaborate, and capture data in the cloud. You can update questions in real time and keep all researchers abreast of the changes. However, don’t do anything more than small changes to the demonstration. Your researcher or team member will need to make the change and share the update to all interview groups before the next round of participants arrive. Also, you don’t want to change the demonstration and questions too much; otherwise, you’ll disrupt the baseline for your control group.

Extracting succinct notes

The reason you conduct guerrilla user research is that at the end of the day, 90 percent of the work is done, the information is organized, and your team has some action items to do. So, your note-taker is a very important component on this day. He should ideally be typing notes into a computer document during each interview. You can even have him type it directly into the UX Strategy Toolkit so that the information is viewable by the team in real time. If he is taking notes on paper, he had better be fast; immediately after the interviews he’ll need to transcribe notes into the cloud or into a document that is shareable with the team.

During the interview, the note-taker should not worry about spelling. She can go back and fix it later. She should try to distill participants’ responses into short sentences that encapsulate the essence of their responses. She should focus on capturing answers (see Figure 8-8) to script questions without noting additional insights — that can come later when there is a lull between interviews and team members can talk. Or, it can come at the end of the day when the note-taker can clean up the data a little and provide insight into how to fine-tune a solution or pivot.

Figure 8-8. Team members Bita (middle) and Ena (far right) during the Solution demo portion of the interview at a Culver City café. Participant on the left.

During or after the interviews, the note-taker or you can also color code the spreadsheet to help make the analysis quicker (just as in Chapter 5 when you analyzed the competition.) A major pain point would be color-coded red. If a key experience or product concept received an easily fixable response, the note-taker could color-code it green. Feel free to develop your own system.

Analysis Phase (Two to Four Hours)

As I described at the beginning of the chapter, my team and the software engineer didn’t need to analyze our findings after the guerrilla user research. It was clear that the business model didn’t work. The users we interviewed were interested in the value proposition, but they couldn’t afford or were not willing to put down a large enough sum of money Hotels.com-style to sustain the business model. The product, as it was, needed a direct channel to an affluent customer segment.

However, if it’s not that obvious, the analysis phase involves synthesizing all the feedback from the interviews to determine your team’s next action. Did the guerrilla user research validate or invalidate your assumptions? Was the experiment a failure because the execution was sloppy? Or, did something unforeseen occur such as in the case of the treatment center operation, in which we learned the business model did not work? Your goal is to use the analysis as a decision point to pivot in a different direction or double-down on further experiments that actualize the value proposition.

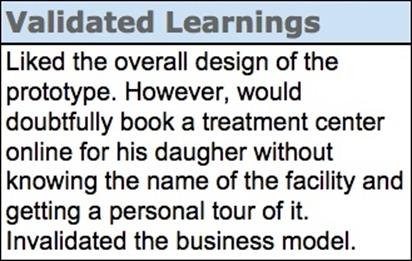

At the bottom of the template is a row called Validated Learnings. This is where you can put your high-level findings for each participant and track which participants either validated or invalidated your solution hypothesis, as shown in Figure 8-9.

Figure 8-9. Validated Learnings sample cell

To do the analysis, you need to take a step back as you did in Chapter 5. Zoom out from all the details that you were just bombarded with and think carefully about the big picture. You might find yourself doing one of these things:

§ Assess to determine if the correct customer segment was reached, by looking at your provisional personas or initial customer discovery research. If it was not the correct customer segment, begin making new assumptions about the right one.

§ Assess if the problem that your product is trying to solve is an actual problem based on the feedback that you heard. Was it a small problem or a big problem?

§ Assess if the solution that you showed was on target. If people were not truly excited about the value proposed in the solution prototype, think through possible ways to improve it.

§ If the value proposition was validated, congratulations! However, don’t stop there. Determine if there are any easy fixes that can be made to improve the user experience.

§ If the value proposition was not validated, assess why immediately. Was it because you had the wrong customer, problem, and or solution? Is it fixable? How can you change the product or user experience?

§ Listen to the signal. If the experiment was an abysmal failure, resolve to take a break while you reset your entrepreneurial or intrapreneurial clock.

§ If you have a client or stakeholder who does not believe in your research and wants to build the product regardless, you face an existential challenge wherein you are trying to balance your principles and your pocket book. Only you (and your spouse) can answer this one.

Enter your insights, answers, and conclusions into a spreadsheet in the UX Strategy Toolkit at the bottom of each participant’s column quickly. You want to make the turnaround on your team’s decisions fast.

You are now at the end of your guerrilla user research, and you are once again at a crossroads:

§ You invalidated your value proposition. If you are wrong about your original customer segment, go back to Chapter 3 (customer discovery).

§ You invalidated your value proposition. If you are wrong about your solution, go back to Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6, and Chapter 7

§ You validated that you have product/market fit. Go build a functional MVP and move on to Chapter 9

Recap

Conducting guerrilla user research (especially with stakeholders present) can feel intimidating at first, but the more you do it, the less scary it becomes. It has the benefits of immediacy and transparency. Plus, your entire team and the stakeholder will be better off learning sooner rather than later if your solution works. Plus, you do it as a team; everyone is equally invested in the outcome. They have the benefit of really seeing how users will experience the product.

[56] Klein, Laura. UX For Lean Startups. O’Reilly Media, 2013.

[57] Buley, Lean. The User Experience Team of One. Rosenfeld Media, 2013.

[58] http://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/06/technology/for-technology-no-small-world-after-all.html

[59] Rudorff, Raymond. War to the Death: The Siege of Saragossa. Hamilton, 1974.

[60] http://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-many-test-users/

[61] Maurya, Ash. Running Lean: Iterate from Plan A to a Plan That Works. O’Reilly Media, 2012.

[62] Portigal, Steve. Interviewing Users, Rosenfeld Media, 2013.