Eliminating Waste in Business: Run Lean, Boost Profitability (2014)

Chapter 2. Strategy of Waste

Waste at the Strategic Level Creates Waste Everywhere

There’s only one growth strategy: work hard.

—William Hague

In the business world, we tend to equate growth with success. In both the business and academic worlds, we seem to be obsessed with the fastest growing companies, the largest companies, and the companies that have the most rapid increases in stock price. In fact, public companies traditionally receive high praise and recommendations for investment possibilities because of their capability to deliver rapid earnings growth, along with quickly rising stock prices, despite any real qualitative factors about the true well being of the company.

However, in one of the seminal books on strategy, George Day, in 1990, warned of overcapacity. He stated that all markets/industries in America suffered from chronic overcapacity by 15–40 percent, depending on the industry.1 We’ve known this for over two decades. We think most people have grown tired of the whole “hyper-competition” subject, the idea of “saturated markets,” and concepts like “how to stand apart from the clutter.” Now, overproduction has reached China as well, to the point at which more than 1,400 companies in 19 industries in China have been asked to reduce their production due to overcapacity.2 So, why more than two decades after being warned about excess, and now experiencing international excess, are we still obsessed with growth? Why is growth still our number one goal and the foremost indicator of a sound strategy?

![]() Note Long-term growth is not always profitable or sustainable. Only grow when it makes sense, based on the market conditions. When it doesn’t make sense, be satisfied with profitability.

Note Long-term growth is not always profitable or sustainable. Only grow when it makes sense, based on the market conditions. When it doesn’t make sense, be satisfied with profitability.

We believe that this whole growth mindset is skewed in the wrong direction. It has set the template for how businesses are managed and how strategies are created. But growth should never be the goal by itself. Growth is not a goal. It is a consequence of meeting other goals.

In fact, we believe that a goal of growth leads to downward spirals. It leads to generating innovation for the wrong reasons and cheapening quality for the sake of growth. It leads to a desire to expand without considering the market or the industry factors. It leads to managers constantly trying to revamp and update the strategy. It leads to excessive, misunderstood, and pointless benchmarking, as everyone is always trying to “keep up with the Joneses.” It leads to unnecessary innovation and financially unsound mergers and acquisitions.

Having growth as a strategy often leads to internal excess and waste. This chapter focuses on how to make strategy more efficient and effective, how to take strategy away from what everyone has likely heard in business schools, and how to focus on key factors other than growth. It is only through a focus on efficiency and on the customer that a company can see long-term growth.

CREATING A LEAN ENTERPRISE

In the words of George Day in 1990, winners are focused on two things: a shared strategic vision and responsiveness to marketplace/customer desires. This is still true today. Managers must create a stable, common-sense strategy that everyone in the company can implement and that is based on customer desires. The only thing that has changed in the last decades is an additional emphasis on efficiency and quality, because markets are now even more saturated. Using these principles, managers need to work to create a lean enterprise.

Prime Areas of Waste

We organized this book to focus on waste in the typical functional areas of business, so there is overlap between chapters. In this chapter on strategy waste, the primary source of waste is the creation of the strategic plan itself—and, unfortunately, the creation of this plan seems to be atremendous source of waste. But we will also focus on other areas of waste created by strategy. Some of these are ineffective leadership, lack of tangible outcomes in a strategic plan, benchmarking, and pointless growth. (Many of the specifics about these areas of waste are discussed later in this book in their respective chapter. For example, if you feel you have waste caused by ineffective leadership, refer to Chapter 5 on human resources.)

Waste from an Ever-Changing or Unattainable Strategic Plan

Every company needs to have a strategic plan, but the frequency and level of planning that companies undertake is often much too extensive. For the small to midsized companies, for example, a strategic plan should last for several years and sometimes even decades or longer. In a larger organization, there should be an overarching strategic plan that lasts just as long. For instance, a company like General Electric would have a General Electric strategic plan and plans for each division, such as GE Financial, GE Transportation, and GE Appliance. This is due to the breadth of the organization and the differences between the business units. Even in these large organizations, planning too frequently can be counterproductive and wasteful.

But before we can get into how strategy is wasteful, we need to focus on what strategy is—or more importantly, what it should be.

What Is Strategy?

We have heard many times in our careers that strategies should be ever changing, innovative, and hard for competitors to predict. Many times, strategy is described as a maneuver on a battlefield or a football field. Anyone who says this doesn’t understand strategy. Strategy is constant. Tactics change.

Think of Amazon.com. They have had the same basic strategy for almost two decades. They amazingly have no innovative products or services, no great technological geniuses, nothing extraordinarily remarkable, and nothing that can’t be readily copied. Their success flies in the face of everything we learn in business schools about competitive advantages and the resource theory.

![]() Note Strategy is constant. Tactics change.

Note Strategy is constant. Tactics change.

One of the first theories about strategy and competitive advantage was the resources-based view. In that view, in order for a firm to have and maintain a competitive advantage, it needed to possess resources that were rare, valuable, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable. The capabilities view of the firm came out shortly thereafter and essentially said the same thing, but in regard to processes instead of resources. More or less, the company had to do or possess something that competitors could not easily have, do, and copy in the near future.

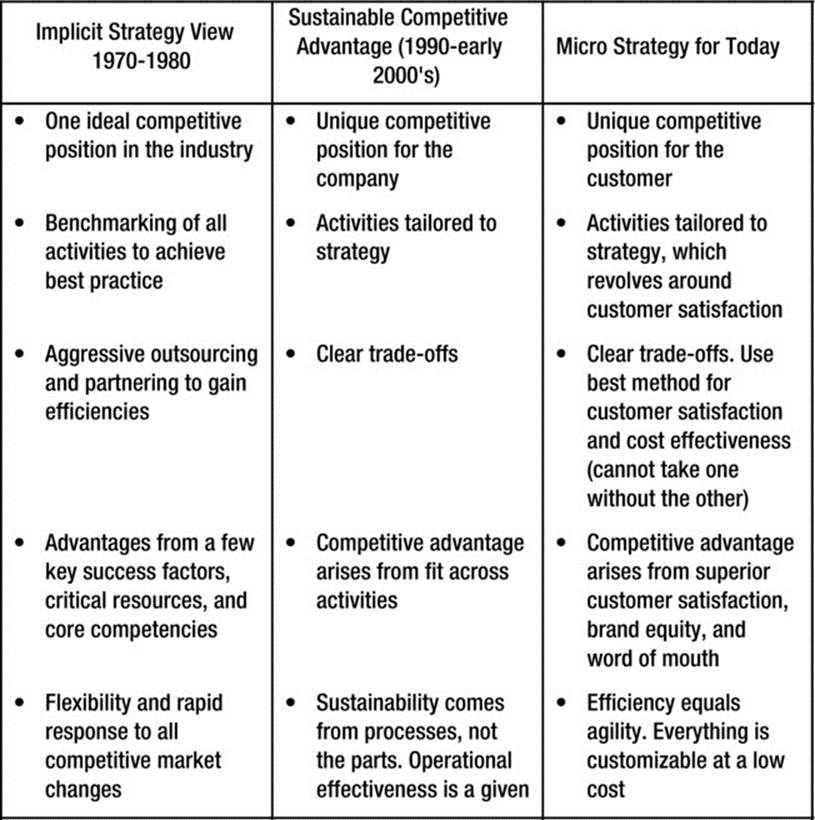

Then, a wave of business school research came out touting the advantages of the learning organization. In this view, firms should collect information, process it, disseminate it, and ultimately learn from it. This was all done in order to innovate and change. The company would always be changing and adapting to customer trends, with the goal of outpacing the competitor by keeping up with the customers’ ever-changing needs. Figure 2-1 shows the evolution of strategy.

Figure 2-1. The evolution of strategy. Source: Heavily adapted from Porter, Michael, “What Is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review, November/December 1996, pp. 61-78

Let’s go back to the Amazon.com example. Why are they obviously winning and killing everyone else around in numerous categories (Borders Books and Best Buy)? They have no rare, valuable, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable resources or capabilities, and they sure aren’t making any mass moves. You could argue that they have had some changes, like those with the Kindle, but let’s go back to what strategy is. We looked around and found the definition we liked best, of all places, from ehow:

“Organizational strategyis the creation, implementation, and evaluation of decisions within an organization that enables it to achieve its long-term objectives. Organizational strategy specifies the organization’s mission, vision, and objectives and develops policies and plans, often in terms of projects and programs, created to achieve the organization’s objectives. It also allocates resources to implement them.”3

That’s it. An organization needs to figure out what it does, make sure it is feasible, and do it the best they possibly can. They need to do it with a complete customer focus in mind, at the most broad level. Sure, things have changed in 20 years for Amazon.com. Customers now expect free shipping, and they want to read reviews before buying products. But, the basics are still there. Where can a customer go to buy anything, in the most convenient way? There’s nothing terribly secret about that. It’s just that everyone else seems to be more focused on finding something rare or learning and innovating toward the next greatest thing.

STRATEGY: IT’S EASIER THAN YOU THINK

We cannot make this any simpler. Stop reading all those books on strategy and holding strategic planning sessions. First, figure out a feasible plan of action for what you do best. Make sure there is a customer need. Note that we’re not even saying unmet need. Because there really aren’t many unmet needs left to be fulfilled. The key is that you are going to find something you do well, and you are going to do it well. At least good enough to have exceptional customer satisfaction, which will lead to brand loyalty and word of mouth. You will not change it or modify it because your strategy is going to be specific enough to provide direction, but not so specific that it does not allow for change. Amazon.com did not out set out to be the best paper book distributor (or they would not have called themselves Amazon.com, they would be “Book-A-Plenty.com”). Instead, they set out to be a massive online distributor. This implies that Amazon.com must have exceptional warehousing and Internet systems, but does not lock them into any particular product. All of their most valuable metrics and analysis tools should involve things like speed of delivery, user search functions, ease of buying for the customer, and other similar metrics. They need to make sure that customers go to Amazon.com when they’re thinking about shopping online and they need to understand why. They will not change unless people stop buying online. This is all there is to strategy. Stop wasting resources by making it more complicated than that.

![]() Note Stop overcomplicating strategy. Figure out what you do best and do it the best.

Note Stop overcomplicating strategy. Figure out what you do best and do it the best.

Developing a Strategic Plan

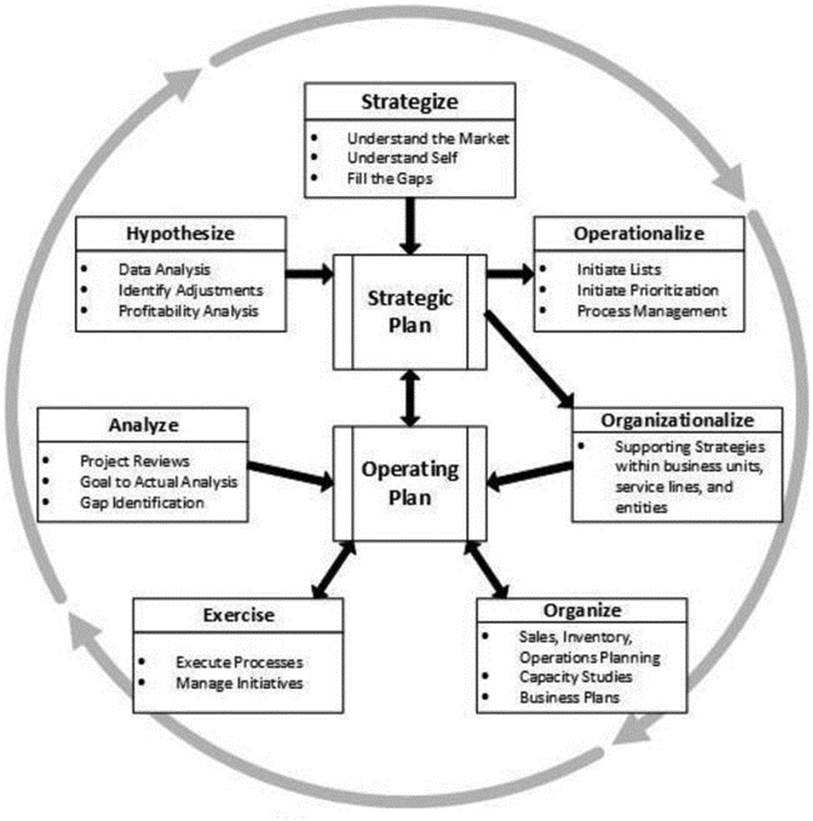

The process of determining the strategic plan includes compiling data on yourself and your competitors. After the data is analyzed, you must identify any gaps and develop strategies to address these gaps. Once you develop a good plan and set good metrics, you should use the Hoshin Kanri process (see Figure 2-2). This process eliminates the need to do special data analysis projects, since these metrics are likely ongoing measures used in the business. It also makes sure that when the strategy is initially created, all the proper groups have a say. This will lead to a stronger strategy and more consensus in the long term. Finally, this process includes the implementation plan and the metrics as part of the strategy. Waste is reduced by setting up a lean structure in the beginning.

Figure 2-2. Hoshin Kanri Process

Understanding What You’re Good At

If you are going to develop a strategy that does not cause waste, you first need to understand what you are good at. You can start with a SWOT analysis, taught in all MBA programs. Keep in mind that SWOT analyses should not be done every year. We are assuming that you are either starting with a new company or at a loss in terms of what you are good at. The elements of SWOT are simple:

· Strengths: What are you good at?

· Weaknesses: What aren’t you good at?

· Opportunities: Where can you take advantage of the market?

· Threats: What are you at risk of losing to your competitors?

Please realize that SWOT should only be used to organize your research. It is not an analysis tool. You also have to remember the adage, garbage in, garbage out. Your information will be incorrect if you are not basing it on sound data collected from relevant departments in your company using the right metrics.

Understanding Your Market

Understanding yourself is the first step to developing a strategy. The second step is to understand your market. (These steps are intertwined.) You must understand these both in order to determine if you have something to offer that you are not currently offering, or if you can expand what you already do well. You need to understand yourself first, because otherwise, you may be tempted to try to be something that you cannot do and waste resources on failure. After you understand your company, you can focus on your customers’ needs. This understanding of market needs comes from market research (covered in Chapter 3).

Developing the Strategy

Once you have identified opportunities that match your capabilities, it is time to develop a strategy. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line (see Figure 2-3). Strategy is the method you use to plot that straight line.

Figure 2-3. Strategy as the Straight Line

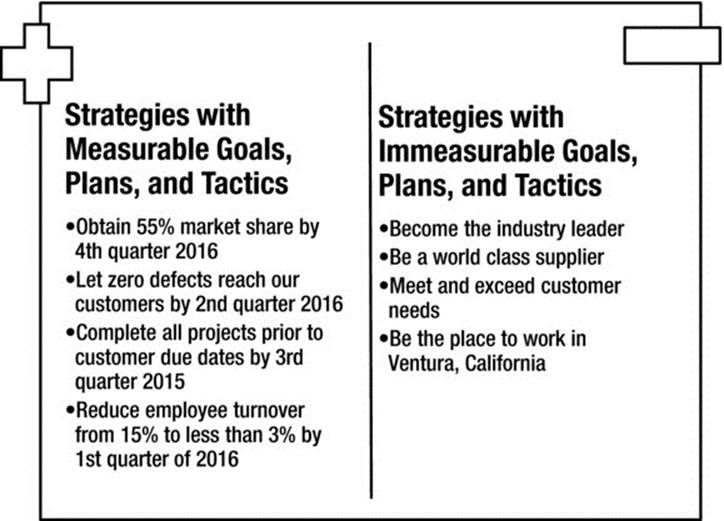

Too often, companies develop mission and vision statements and set up immeasurable goals without a real plan to reach those goals. See Figure 2-4 on these differences. This is often called strategy. This is not strategy. Strategy is the roadmap between where you are now and where you want to be. Therefore, there are probably turns that you need to take on the path to meet your goals. This is strategy.

Figure 2-4. Measurable and Immeasurable Strategies

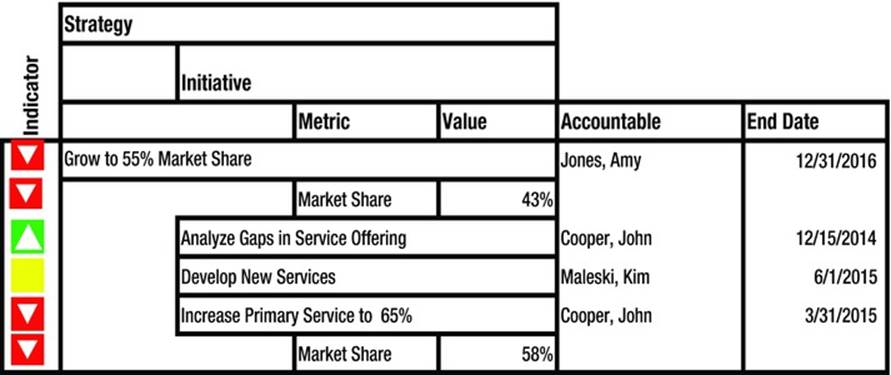

From there, you start to develop tactics. In order to build these tactics, you identify gaps between the current and future state of the business. The steps to fill these gaps can be placed on a timeline, with clear, measureable goals assigned to each phase. Each phase may represent six to twelve months. Once this plan is assembled, you assign tasks to implement the first phase and track each action to show progress toward that phase’s goals. Every three years, you should revisit the strategy (not necessarily to re-create it). You do this because, as the company matures, different long-term goals may be necessary or outside forces affect the current plan. But again, we want to urge you to use consistency in your strategic planning. You can see how you should track the initiatives associated with each strategy in Figure 2-5.

Figure 2-5. Initiative Tracking

![]() Note Strategy is based upon a series of tactics. In this way, it is a roadmap, not a destination.

Note Strategy is based upon a series of tactics. In this way, it is a roadmap, not a destination.

OUTSIDE FORCES: A REASON TO CHANGE STRATEGY

In 2010, when the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was signed into law, healthcare providers were forced to revisit current strategic plans. This is an example of why it is important to continue to revise strategies as outside forces change. In this case, failure to do so would result in not being able to operate under the new regulatory and payment systems. Similarly, in the late 1990s and 2000s, companies were forced to realize that nearly everything might potentially become electronic. This change especially impacted brick-and-mortar retailers. Although these are extreme cases, the point is that outside forces can force change. Don’t be guilty of being too committed to your plan. Instead, your plans need to be flexible enough to allow for market changes. That is not to say that you should change your plans frequently. If you have a good plan, and there have not been significant changes in the business environment, stick to that plan. Don’t waste time replacing an effective strategy.

Executing the Strategy

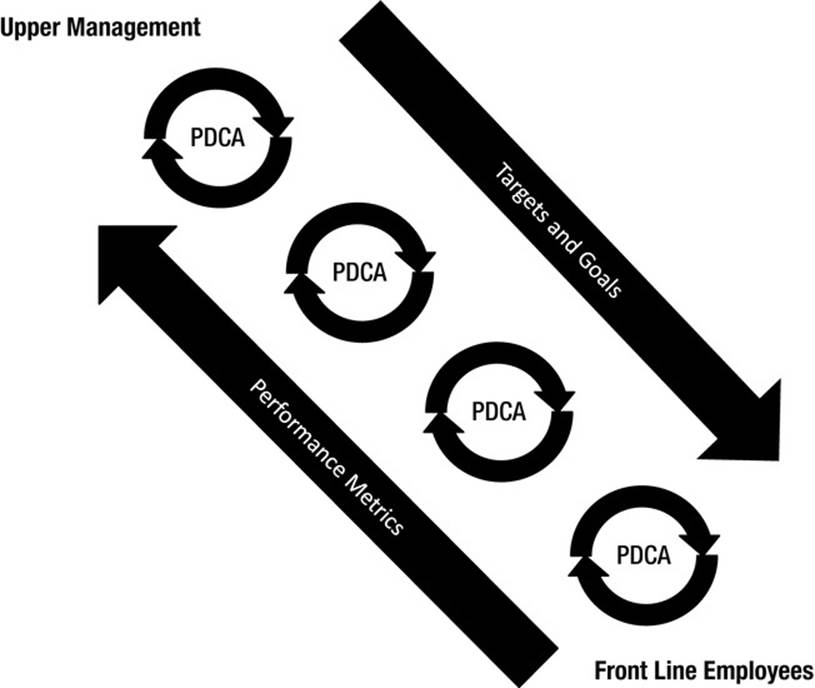

Strategic plans need to be simple enough for the average employee to understand his part in their implementation. This is a simpler task in a small company than in a large one. Strategies of small companies often are more tangible due to the nature of the business, whereas large companies develop more grandiose strategies that seem to have no real bearing on their daily operation. Note that it should not be this way. All plans—for small and large companies—should be implementable. Effective implementation of Hoshin Kanri is necessary for successful strategy execution. Hoshin Kanri helps management translate strategies into implementable goals and actions. Upper management sets the corporate strategy and drives the strategy through tangible goals and projects at each level of the organization. Figure 2-6 shows a simplified representation of this concept. Each level of the organization can use PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act), developed by Dr. Deming, in order to drive performance improvements.

Figure 2-6. Hoshin Kanri Simplified

At each level of the organization, initiatives are designed to support the strategies of the levels above it. This concept makes the sometimes vague strategic plans tangible for every employee, although there are challenges to implementing them. These challenges include being able to dissect the strategies into smaller and easily understood pieces. Large corporate strategies are often difficult to simplify. Of course, if we expect them to be executed, we must be able to get the company to understand them. It is therefore a good idea to simplify them.

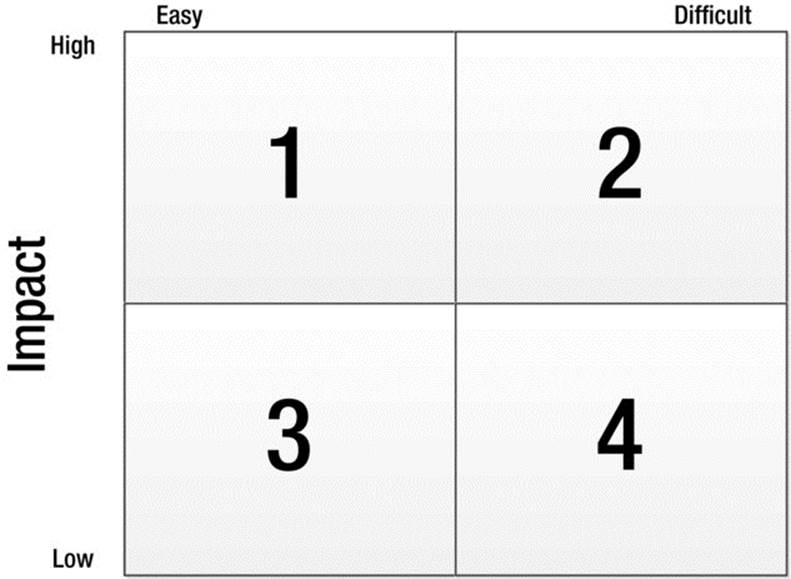

Another challenge is effectively prioritizing the tactics supporting the strategic plan. Most organizations do not make this prioritization process an effective part of leadership. For those without a formal process, an impact/effort matrix, as shown in Figure 2-7, is a simple way to prioritize work. When using this tool, a team assigns an impact and effort for each project. Easy projects with high impact are the first priority. Difficult projects with a low impact rarely get accomplished. The final challenge is using meaningful metrics to show progress on each level of the strategy deployment.

Figure 2-7. Impact/Effort Matrix

These tools, if utilized together and correctly, should help you implement a consistent strategy to run your business. They can help reduce the waste during the planning process.

Waste from Strategy and Management Based on “Fluffy” Outcomes

Until the mid-1950s, growth was about marketing, and marketing equaled sales. The job of the marketing department was to persuade a customer to buy a product. It didn’t matter what the customer needed; what mattered was the product that the company made. Then, persuasion became the name of the game. In the 1960s and 1970s, companies started to see how this mindset wasn’t working. They started to tailor their products to actual customer needs. Unfortunately, this was all lost in the 1980s, 1990s, and still today. Strategy itself seemed to become the most fundamental concept. This was a top-down mindset—CEOs ruled.

Both the practitioner realm and the academic circles exploded with books and research on strategy: how to create a strategic plan, how to create a mission statement, and how to perform a SWOT analysis. All of this study was very “fluffy,” meaning it had remarkably few tangible specifics. It was not based on solid customer needs or research, but instead, just what the CEOs dictated. This trend, coupled with the stock market booms and crashes, seemed to shift the attention of the businesses to the indicators already described, such as growth and stock price.

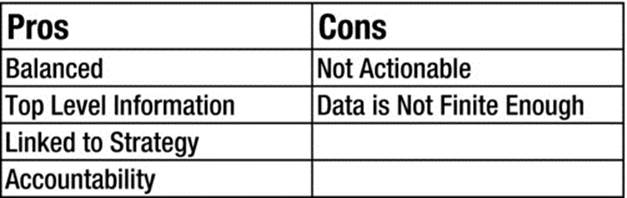

In his popular book, Making the Numbers Count, Brian Maskell outlined the case to accountants and chief financial officers to change the way that they measured business functions.4 These overarching indicators, such as profitability and debt-to-equity ratio, do not provide enough information to get a clear picture of a firm. At least not clear enough to formulate an effective strategy. Maskell discussed new costing methods, process management, concurrent engineering, and life cycle analysis. Dr. Deming started this movement with his criticism of the systems of absorption that are often used in accounting that lead to destructive business decisions.5 Metrics must be relevant to the operations at hand rather than easy to get or commonly used accounting values. Lean Six Sigma methods value this approach because you cannot change the output of your processes by focusing on the output. Rather, you affect the output by understanding the inputs that drive performance.

We learned this in high school algebra through the formula Y=f(X), but have somehow forgotten to consider this when operating businesses. We chase sales through price cutting or by making deals in order to meet a quota, rather than doing what truly drives sales, which is making customers happy. If you analyze the factors that drive customer satisfaction, you’ll have a formula that you can use to drive sales through service and value, rather than less healthy strategies. It is not the output that matters, but rather the inputs. You should measure the Xs, not the Ys.

![]() Note Use Y=f(X) in all situations. Don’t drive your business by focusing on the results. Focus on the things that drive results.

Note Use Y=f(X) in all situations. Don’t drive your business by focusing on the results. Focus on the things that drive results.

Accounting measures happen in monthly, quarterly, or annual cycles. This is far too infrequent to adequately affect operations. Rather, if you focus on measures that predict the monthly financials, you can drive those inputs, view them on a regular basis, and improve overall performance. Many of you have heard of SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-Bound) goals, but still try to run your businesses without them. Business success is not typically the effect of making one or two great strategic decisions; it’s the direct result of making intelligent decisions every day. In order to make effective decisions, you need real-time data that influences management. You also need the experience and industry knowledge to react to that data and to improve performance.

Strategy must include the overall vision of the organization as taught in MBA schools. But it must also go way beyond what is taught in these classes. It must also include steps that are necessary to achieve this vision. We see mission and vision statements that talk about being “world class” or “best in class.” We also see statements such as “meet or exceed our customer requirements.” These are cliché strategic phrases that have no real meaning. How do you measure “meet or exceed our customer requirements?” You don’t. However, you can measure things like dock-to-dock time or development cycle time, both of which could predict the ability to meet customer requirements (assuming that your processes are capable of meeting their requirements). If you take the time to develop strategies, you must take the time to understand the variables that reflect the success of your strategy and the inputs that drive those variables. Effective leaders will work on finding key metrics to tie to strategy and then delegate the implementation of the strategy to trusted employees. They do this by communicating the vision and showing what success looks like.

An example of this type of strategy can be found in a company like Aneonline. (We understand this is a relatively unknown company, but unfortunately, it is hard to find companies with great strategies.) This company is a small, online marketplace owned by an Australian company. Aneonline’s strategy is, “We intend to provide our customers with the best online shopping experience from beginning to end, with a smart, searchable website, easy-to-follow instructions, clear and secure payment methods, and fast, quality delivery.”6 Every single one of these desires is specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound. Searchability of a web page can be measured. Payment methods can be assessed. Delivery can be measured for quality and speed. Crafting a strategic plan through goals like “growth,” on the other hand, is meaningless. Strategy must begin and end with measurable goals.

Having measurable strategies is somewhat difficult, due in part to the traditional organizational structure. This structure includes departments including sales, marketing (sometimes included in sales or vice versa), accounting, and operations. Each department is incentivized to be at odds with the others, rather than focus on the overall health of the organization. The performance metrics focus on individual performance and are used in order to incentivize people to improve individual performance rather than the health of the organization.

![]() Note Strategy must begin and end with measurable goals.

Note Strategy must begin and end with measurable goals.

We have essentially taken the fundamentals of what Toyoda taught us and perverted them to fit Western culture, therefore making them less effective. Maybe it is time to consider getting rid of the traditional organizational structure and instead have cross-functional teams that focus on each of the business areas. The concept of sales, inventory, and operations planning used in many organizations is a step in this direction, but does not address the root issue, which is the need for departments to consider the health of the whole company rather than how good each department looks. For instance, we should include operations and sales in investment decisions. The lack of knowledge about the overall operation of the business leads each individual to drive the metrics that he feels are important. In some cases, these may be the right metrics, but in many others, they are not. It is impossible to develop a strategy at the upper level of a company, when the individual department’s needs are not known, considered, or integrated. (We discuss silos later in the chapter.)

Not having a measurable strategy creates waste everywhere in your company. Everyone is running in every direction doing things with no purpose. The first step to a waste-free company is a good strategy based on the ideals outlined in this chapter. Measure the Xs, not the Ys.

Waste from the Strategic Planning Process

The strategic planning process is normally extremely wasteful. Strategic plans may be hashed out in a retreat format, which deserves some discussion here, although we discuss retreats more in Chapter 5. Why is a retreat wasteful? Taking leaders out of the daily activities and focusing on a topic or issue is not necessarily a wasteful activity, but unfortunately too many retreats include special amenities like hotel stays and country club conferences. They may also include offsite team building or brainstorming sessions. These activities are all wasteful.

If you need a retreat in order to focus, then grab a space at the company and tell everyone to leave you alone. This way, company resources are not wasted on an offsite location. Skip the team-building exercises. These are neither true rest-and-relaxation events nor something more meaningful than discussing how the leaders can work better as a team. These conversations are too often guarded and a complete waste of time. We have all been part of these wasteful events far too many times.

![]() Note The cost of developing strategy is inherently wasteful. Don’t add retreats, spas, catering, and more to the mix. Respect your workforce. Plan strategies in an efficient manner. Keep in mind that having a strategy that is not executed or understood is even more wasteful.

Note The cost of developing strategy is inherently wasteful. Don’t add retreats, spas, catering, and more to the mix. Respect your workforce. Plan strategies in an efficient manner. Keep in mind that having a strategy that is not executed or understood is even more wasteful.

Instead of the aforementioned wasteful strategic retreats, consider this strategy session from our experience that was beneficial. The company in question brought managers from multiple manufacturing locations together to standardize operations and reduce waste. It had never been done before and had a specific purpose. They didn’t rent conference space; instead, they set up folding chairs in an empty space in the warehouse. Of the various strategic planning sessions that we have been part of during our careers, this was the best one that we can remember. They didn’t spend time on SWOT or multi-generation plans, because they already knew where their opportunities for improvement were. Everyone was aware of the session beforehand and came prepared with applicable information in hand. We exited the one-day meeting with a clear path to standardize operations and share best practices. How was this different from other strategic plans? It included the following:

· Focus: Too many organizations haven’t identified the reason for their strategic plan. They put together the plan because that is what they are supposed to do. After all, their MBA professors told them they should and they have seen other companies do it, right? If the business is doing well, then why bother? If there is a gap, focus on that gap. Develop a plan to sustain current successes and bridge the gap to get where the company wants to be.

· No soft stuff: Trust falls don’t build teams. Golf and obstacle courses don’t build teams either. Teams are built though mutual respect and accountability, and by working together on work that needs to be done. The “soft” stuff you do at retreats and strategy sessions won’t build your team. It is an excuse to have recreation on the company’s dime. In the age of downsizing and infrequent pay raises, this is not only wasteful, but is belittling and cruel to the employees.

· A path forward: The outcome of the strategy must include a plan for execution. Nobody should walk out of the planning session without knowing what they or their department is doing to drive the strategy very specifically.

· Respect: Again, it deserves mention, leaders need to respect their stakeholders and avoid elaborate expenses for these sessions. What is the definition of elaborate? Anything outside of meals and beverages should be questioned. If the company possesses an internal resource, then why would they waste money on renting the same resource?

Business has changed over the last 20 to 30 years. It used to make sense to build business units around the world to serve regions and have sales offices in those areas as well. It used to make sense to come together and have “leadership retreats” or even frequent “strategizing sessions.” Obviously, the infusion of technology has made the world a smaller place.

These logistics improvements have also given small and medium-sized businesses the ability to be global without needing locations around the world. There are times when it makes sense to build facilities around the world, such as when a customer builds a large manufacturing location and you want to serve the customer well. This happened when Bosch Siemens Hausgeräte (BSH) built facilities in the United States and China. Some German suppliers built factories near the new factories in order to provide good service to the new factory. Although local businesses got some of the new work that BSH offered, the companies who followed BSH took a large portion of the work. Why did this happen? It was the result of a good customer relationship. We mention this example because these suppliers built manufacturing locations for logistics purposes.

There are many times when logistics become less important. Technology enables companies to hold meetings through the use of Skype or Webex, saving unnecessary travel expense. In fact, with the exception of some types of sales calls or services where physical presence is necessary, the need to travel for business is nearly extinct. We know of a company in Ohio that outsources all of its IT work to a company in California. So why do so many managers and employees travel? There is a lot more about this topic in later chapters, but we will briefly discuss some of the reasons here.

The chief reason is probably why we do many other wasteful things in business. It’s the “we have always done it this way” philosophy. We travel to meetings with other divisions of the organization or to visit customers because we think we have to do it that way. We can’t craft a strategic plan without sitting together in a room to “brainstorm.”

In reality, we can hold most meetings and even technical discussions via the Internet. The downside to limiting business travel is that many employees use this as an opportunity to vacation. Think of the news stories around meetings and conferences held by the Internal Revenue Service or large banking firms. Do we think that these are the only people who do this? It is obvious throughout a company when executives waste money.

We spend so much time in constant communication with employees and customers that strategic planning workshops are frequently a waste of time. Get the data to make informed decisions, make your plan, and move on. Stop the bleeding of excess money in the name of planning.

![]() Note If your strategic planning process has not changed in ten years, change it now!

Note If your strategic planning process has not changed in ten years, change it now!

Waste from Too Much Leadership

Any discussion about strategy must contain a discussion of leadership. We discuss particular aspects of management in terms of human resources and how to calculate leadership/management excess in Chapter 5, and here we discuss the broader idea of leadership.

Management guru Peter Drucker was interviewed by Forbes magazine shortly before his death. In it, Drucker noted that one of business’s worst problems was too much leadership, both in sheer numbers and the whole concept of charisma. He felt that there were way too many leaders walking around and very few actual managers who accomplished things. Additionally, Drucker felt that charisma was one of the most overrated concepts of all time. Charisma accomplishes nothing. In Drucker’s words, “What they really need are competent managers who can do the hard work of decision making, planning, and coaching.”7

As an example, I can think back long ago to my days in college when I paid my college tuition and other bills by waitressing and bartending. Typically, the managers had worked their way up through the company. Every now and then, the big corporation way down in Florida would bring in a new manager who had never waited tables, never bartended, never washed dishes, never cooked, and was never a hostess. These people never lasted more than about 1-2 years. They burned out quickly when they realized how hard the job was, and moreover, when they realized they had no respect from their workforce. They try to replicate this experience in the CBS show “Undercover Boss,” in which CEOs go undercover as workers in the frontline jobs. Typically, the CEOs seem like buffoons trying to do these jobs. Even in this forced and fictitious situation, it is easy to see that some CEOs have absolutely no idea what is required in their companies or how hard it is. You cannot be a restaurant manager without doing every single gross and hard task throughout the day.

This example is extreme, because restaurant jobs can be arguably some of the hardest. But, the lesson is no different in corporations. How can someone set strategy, set up plans to implement strategy, and set up metrics to measure success if they cannot or are not willing to do the work? This statement cannot be translated exactly in all situations. A CEO of a hospital might not know how to perform brain surgery. They might not even be a doctor—that’s okay. What’s not okay is when they do not understand each employee’s job—what they need to know and possess to do the job and how to be successful in that job. They can’t implement and measure strategy without this understanding.

Therefore, Drucker criticizes charisma because charisma in itself does not drive leadership. It is a combination of leadership and management that gets the work done. Not everyone can be a leader. Not everyone can be a manager either. But no leader can be truly effective without solid management skills. Drucker’s criticism of leaders is based on the fact that so many leaders are incapable of management. (With more than 13,000 books written on leadership, there is an obvious problem.) By focusing on good management skills, true leadership can be developed. In reality, leadership roles are often filled through years of service or as a progression through ranks of management, such as in the restaurant example. Leadership, however, should be developed through aptitude and ability.

![]() Note Leaders manage and inspire. One without the other is not leadership.

Note Leaders manage and inspire. One without the other is not leadership.

A TRUE TEST OF LEADERSHIP

Traditional leaders are often type A personalities who may not possess the humility necessary to handle true leadership. Leaders start by leaning on the expertise of those whom they lead. They ask questions about what must be done and how it should be accomplished. The best leaders surround themselves with exceptional people. This is absolutely true. Andrew Carnegie wanted to put on his gravestone, “Here lies a man who knew how to put into his service more able men than he was himself.”8 Effective leaders leverage the abilities of others to maximize their potential and drive organizational success.

Waste from Commitment-Stuck Leaders

Robert Cialdini wrote about the weapons of influence and their effect on the decisions that people make.9 One of these weapons is the commitment and consistency principle. Cialdini warns us that we can become victim to making decisions and then sticking with them, even when they are clearly bad, due to this psychological principle. Have you ever been in a fight with a loved one, and then realized after some time that you were wrong, but still continued to fight? This is the commitment and consistency principle. Leaders are often guilty of this.

I once had a conversation with a coworker about an initiative that we had been working on for a while. Our company had spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to implement this initiative. I commented that it had become ineffective and we should shift our focus elsewhere. My coworker said, “And throw away hundreds of thousands of dollars that we have already spent? We can’t do that; we’ve invested too much.” This is exactly the point. Even if millions are spent on a project, business leaders cannot afford to continue to invest more money just because they are afraid to be wrong and are more concerned with saving face than making good decisions.

Another example of this principle was with a project whereby, in order to make operating improvements, a leader made the decision to spend over $1.1 million on upgrades. Shortly thereafter, an engineer showed that 80 percent of the projected improvement could be reached for about $20,000. So, faced with the decision to spend $1.1 million and have a return on investment (ROI) that would take years, versus spending $20,000 with a ROI that would take months, what did this leader do? Obviously, we are telling this story as an example of commitment and consistency, so he started spending the $1.1 million. Initially, it seemed like arrogance or ignorance. But, after reflecting on the situation, it is clear that this leader had committed in his mind. Even when confronted with data about the inefficiencies of the larger project backed up with a good measurement system analysis, he could not change his mind.

These are just two real examples of situations where valuable resources are wasted due to the inability to see an ineffective project when you have one, and then be able to move on to better projects. This supports the previous advice to have metrics built around initiatives and goals. Then you should use these metrics to make future decisions. If you put the structure in place as you make decisions, then you empower employees to combat the automated response of commitment and consistency that Cialdini identified.

![]() Note Don’t be trapped by your poor decisions; learn from them and move on. Commitment to a poor strategy will cause continuing poor performance.

Note Don’t be trapped by your poor decisions; learn from them and move on. Commitment to a poor strategy will cause continuing poor performance.

Waste from Benchmarking

One of the most frequently misunderstood principles in strategy is benchmarking. Almost everyone does it, yet very few understand when and how benchmarking should be used. Does Apple benchmark against other companies? Of course, any company in a competitive market keeps an eye on the competition, but benchmarking is often not used this way. We seriously doubt Apple spends much time pondering the moves of Microsoft and Motorola, or at least they didn’t when Steve Jobs was around. We’ve seen some recent moves to show they are spending time benchmarking too much, and all for the wrong reasons.

Benchmarking is effective when it is used to cross industry boundaries, such as the way healthcare organizations look at aerospace or nuclear power to develop their own culture of reliability. It can help by identifying some best practices to implement, by finding ways to generate potential savings, or by identifying methods used to increase customer satisfactions ratings. It can also be used as a temperature check. You can use temperature checks to determine if you are a leader or a follower. In other words, benchmarking can help you know how competitive you are as an organization. In one of my former careers as an engineer designing appliance components, I would go to Best Buy and look at the appliances. This way, I could see what our customers, like Whirlpool, Electrolux, or Frigidaire, were offering in their appliances and then see what the prices were and also what the competitors were offering and at what prices. This told me whether we needed to look for ways to improve our designs. It would in no way tell me how to completely redesign a products or a strategy.

Unfortunately, there are more weaknesses than strengths in regard to benchmarks. One downside is the potential cost. Some suppliers of benchmarking information charge tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of dollars to provide the data. If, after you have reviewed the data, you find that you are better than 90 percent of the market, then it is time to rest, right? Wrong! You should also perform an ROI analysis of the benchmark. If, after buying the benchmark (or doing it yourself), and calculating the labor and resource costs associated with analyzing the benchmark and implementing the changes, you do not show a profit, it would never be a worthwhile endeavor.

Companies should look at their own performance to identify targets and improvements. The ROI is much higher this way because you have taken the time to identify the root causes of waste and eliminate them. Plus, how likely is it that you are looking at companies directly comparable to your own? The risk is high that you are not. Even the exact same type of company, in the exact same industry, will not have the same employees, resources, or anything similar enough to be directly comparable. You may make decisions on the benchmark data that cause the company harm, because you’re not comparing like companies.

If you use benchmarking, you should only benchmark the best. Average is not acceptable. Second best is not acceptable. Only the best applies. However, you have to realize that your company is not directly comparable to the ones benchmarked. Specifically, in a mature industry such as healthcare, where lots of data is available, benchmarking is over-utilized. It is measuring poor performance against other poor performance versus continually working toward perfection. There are always some companies that do some things well and some things poorly.

![]() Note No benchmark will tell you what factors are creating great success and which aren’t, let alone how all the various factors interact.

Note No benchmark will tell you what factors are creating great success and which aren’t, let alone how all the various factors interact.

In many areas of manufacturing (but not all), the concept of zero defects is the leading force in quality circles. Statistics are done on samples to show Six Sigma quality of 3.4 defects per million opportunities, which essentially equates to zero defects. Other companies still rely on acceptable quality standards driven by standards, such as MIL 105-E. With this standard, the company accepts a low level of defects instead of zero, feeling that for the price of the product (generally a very low priced product), they cannot expect zero defects. It is no wonder that we have injuries and recalls in the manufacturing world. The sad thing is that the manufacturing environment is about as good as it gets.

Many financial institutions are so accepting of defects that they do not keep a single profile on the consumers they serve. This leads to potential fraud because all of the divisions do not have the same view of the customers. Healthcare is no different. Donald Berwick has spoken and written multiple times on the inefficiencies and lack of quality in the healthcare field.10 In healthcare, a certain level of defects is considered acceptable as long as it is in line with the poor quality of such facilities. This is not because the customers want defects (who wants a healthcare defect!?), but rather because the companies expect defects since the benchmarks show that all companies have defects.

Benchmarking should never be used in this manner. In cases where you look outside your industry, like healthcare looking at manufacturing to see how they handle zero defects, it might not make sense. Benchmarking in the same industry almost always yields mediocrity, which will never generate an ROI, which will always lead to waste.

![]() Note Benchmarking can be an effective tool for determining how you stand in the market or even for getting ideas for process innovations, but when it’s used to copy others or to set targets, it will lead to mediocrity and underutilization of the company’s potential.

Note Benchmarking can be an effective tool for determining how you stand in the market or even for getting ideas for process innovations, but when it’s used to copy others or to set targets, it will lead to mediocrity and underutilization of the company’s potential.

Waste from Growth

Michael Porter talked about the growth trap over 15 years ago in his paper on strategy in 1996, yet we still see and hear about growth being a strategy. Porter said growth has a “perverse effect on strategy”.11 It incentivizes companies to go after the big customers for a quick win rather than building long-term and mutually beneficial customer relationships. In order to obtain the large customers, lower prices are offered, which limits profitability. The alternative is to grow by selling in low volume to customers willing to pay a higher margin for quality. Notice that there is still growth with this strategy, but there is a clear difference between growth as a strategy and growth resulting from customer service and excellent value. The former is a recipe for declining profits or a desperate move to reach some financial target, whereas the latter is a recipe for long-term profitability and appropriate growth, which the company can most likely handle without major investments.

We have witnessed management making changes to strategy that include adding features that customers don’t really want, trying to steal ideas from other companies, and acquiring companies that have no real value to boost the overall revenue or to enter into new sales channels. The desire to grow confuses the company because—rather than having an internal strategy to make good products or provide services, which provides direction—the strategy is handed to the company by the highest bidder with the most volume to offer. The company identity dies in the wake of a growth strategy. Without this identity, it is increasingly difficult for managers to make decisions without a mistake, so all decisions must go through leadership.

We talked briefly on using growth as a strategic decision, but what is growth? Is growth an outcome that you are looking for? Why do you want growth? Will it make your company more profitable? Believe it or not, there is not a linear relationship between growth and any outcome that a business is striving to achieve. Growth has been studied since the 1950s and nobody has ever been able to come up with a formula that will drive it. McKelvie and Wiklund studied growth and found, “Despite hundreds of studies into explaining firm-level growth differences from 1950 until now, researchers have been unable to isolate variables that have a consistent effect on growth across studies.”12 It’s not great leadership, it’s not great employees, and it’s not great customer service. Growth is created by a set of circumstances unique to each company in which it happens. There is no one thing that leads to growth. (Which again explains why benchmarking in ineffective).

A study was done that looked at the growth hypothesis.13 In it, the authors found that leaders who sought growth without profitability first, failed. This is like the company seeking growth through investment capital. The only way to have successful growth is to have profitability first. This is clearly shown. Thinking that growth brings profitability cannot work. That is, as the phrase says, “putting the cart before the horse.” Leaders who focus on the inputs that drive growth, rather than focusing on growth itself, will be significantly more successful. The inputs must be the focus, not the growth.

Too often, businesses try to become something they are not for the sake of growth. Every business has something that it does well and no business is good at everything. General Electric (GE) realized that it was trying to be good at everything. Even with 140 years of innovations from General Electric, they decided to sell the GE Plastics division to Sabic. Why would they do this? Because, with the exception of their appliance division, GE is not good at being a low-cost producer. They pride themselves on innovation and quality, which directly competes with low cost. (For this reason, it is surprising that the appliance division has not been sold as well.)

When GE was successful in the plastics world, it was because they developed innovative plastics and could charge a premium for them. Customers think of Lexan® or Plexiglas® when polycarbonate is needed even though there are dozens of polycarbonate options. When GE lost this advantage and customers demanded competitive prices and service, GE found that the plastics business was not as profitable as the other divisions. Therefore, they sold the plastics division to a company that could increase the margins or be happy with lower ones. Most businesses are not this insightful and would have tried to hang on to the plastics business.

Growth can mean growth in sales profitability, customers served, or number of employees. The goal of any business is to make money. Even not-for-profit businesses must make money to pay employees and have reserves to handle fluctuations in business. Does growth equal higher profits?Chapter 3 talks more about marketing and sales wastes, but the pursuit of growth while reducing profitability is a main waste of sales and leadership.

So companies think that growth will increase profits. Maybe growth will give them more purchasing authority or give them more negotiating power with their customers. Erie Plastics from Corry, PA thought growth would make it profitable. That was until it became bankrupt when its biggest customer, Proctor & Gamble, chose to stop working with it. Similarly, Core Systems, LLC, of Painesville, OH grew to nearly $50 million from around $20 million over 15 years. Although it had a modest, but solid average increase in sales of about seven percent per year in revenue, it didn’t save the over 400 employees who were laid off when Whirlpool Corporation stopped buying from Core Systems In both of these situations, they had a well-run business with qualified leadership and dedicated employees. Growth was the Holy Grail to achieve stability and long-term profitability. Growth led them both into making deals with massive companies, who would never value the relationship. Growth did not work out in either case.

This is a common formula that we see when we read business publications. It is so common that books have been written challenging the whole notion of growth. In the consumer market, growth creates more liability due to a potential increase in litigation. If you have taken a business law class, you have probably learned about the company with deep pockets. You don’t sue poor people, you sue filthy rich people. Generally, once a company becomes large, that’s when you start seeing discrimination lawsuits or product negligence lawsuits. Likewise, once a company becomes public, you begin to see the drive to pay investors, which frequently causes the leaders to cheapen products. This eventually pushes customers away due to low-quality issues. Yet, business schools teach that businesses must grow. Business leaders feel that growth is a measure of success.

If we assume that growth is the answer, how do we grow? Is it a fault of leadership or lack of resources or capacity? When faced with growth opportunities, businesses often look for loans or investors to fund the resources necessary for growth. This puts stress on the company. In order to meet the covenants on loans, the leaders make decisions to drive short-term targets at the potential expense of the company. We are not saying that companies should not attempt to grow or even take out loans to fund growth. We are saying that growth should be stable and achievable, based on real market factors. Resources should not be extended to the point of potential failure to achieve growth. It is better to grow slowly through happy customers with a real demand, who are willing to pay a decent margin, than by methods that commit you to success or failure based upon “false” growth. Rapid growth is greedy. And we all know how bad greed is. We have outlined some of these growth myths here:

· You can outgrow an organizational or leadership problem. Bad decisions happen regardless of the size of the company. Growth will not solve the problem, but magnify it. This mindset is similar to a married couple having a baby to “save” their marriage. The baby just brings more problems and more stress. The same thing happens in a company. The company must have a good foundation before growing.

· Growth equals profitability. As a young engineer, I frequently heard this justification for lower prices: “we will make it up in volume.” This is like the idea of making something more efficient without improving its quality. You will only make additional bad products quicker if you make a bad process more efficient. The same holds true for growth. Growth will magnify the loss that you will have if you lower your prices and therefore lower margins.

· Profitability improves when you control the market. When you control the market and it is profitable, other organizations will enter the market and become competitors, either through a similar product or a substitution. This is a fundamental idea that Michael Porter discusses in his books. You will have increased profits only when you have something special: good customer satisfaction and brand loyalty. It is not a function of growth.

· If you grow, customers will benefit. How exactly will customers benefit? If you realize savings through growth, perhaps by economies of scale, however rare that normally is, you would doubtfully pass those savings on to the customers. Also, you will be distracted from servicing your existing customers as your customer base grows. You may need to hire additional people to service your customers, which may lower the quality of the service. And if we believe that fast-growing and highly leveraged organizations are less able to adapt to change, how do the customers benefit from that?

![]() Note Grow only when it makes sense for your market or you will end up eroding your margins and losing your competitive advantage. And please remember, growth itself is not a strategy. That only creates waste.

Note Grow only when it makes sense for your market or you will end up eroding your margins and losing your competitive advantage. And please remember, growth itself is not a strategy. That only creates waste.

Waste from Mergers and Acquisitions

How many of you have been part of a merger gone bad? We have seen at least six mergers or acquisitions (M&As) in our careers at different companies where the goal was to create synergy or growth through new customer bases. In five of those cases, the profit that was promised was not achieved. Customers at the acquired companies were either not profitable or chose to leave shortly after the merger. The only time it worked was when the founding manager continued to manage the acquired company and was incentivized as part of the acquisition to meet certain financialmetrics. On the whole, M&As simply don’t add much value.

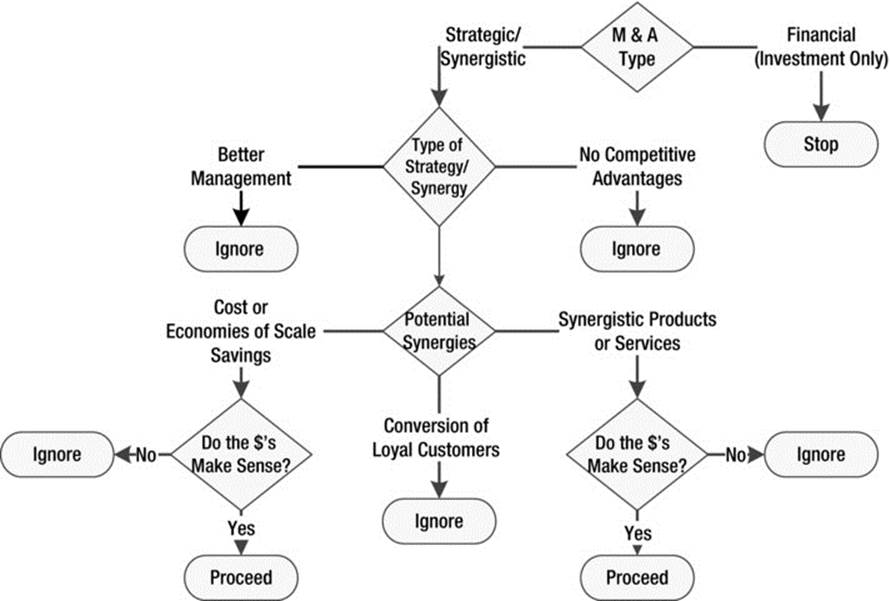

M&As happen for a variety of reasons. See Figure 2-8, which summarizes different types of mergers and acquisitions, including when they can be beneficial. When M&As are made for simple, financial, investment reasons, shares of the acquiring firms decline by an average of 4 percent at the time of the acquisition.14 This number is significantly understated, because it doesn’t account for the average 30 percent premium over the actual book value of the acquired firm, which is typically paid.15 Then, over the next five years, shareholders see a 20 percent decline in the value of their stock, on average.16 Based on these averages, you have to be going against all odds and being extremely lucky to benefit financially from an M&A.

Figure 2-8. Mergers and Acquisitions

Strategic mergers and acquisitions can sometimes provide a profit. If there is no competitive advantage or synergy, obviously, they don’t work or add value. Even when there are synergies, there might not be a good reason to go ahead with a merger. Michael Porter examined 33 large companies that had performed mergers from 1950–1986 and found that these companies had divested far more companies than they had retained.17 Subsequent studies show that on average, M&As performed for synergist reasons do have an increase in operating margins, but these margins run in the range of 0.2 to 0.4 percent. Given the premium price normally paid to acquire a company, these M&As rarely make sense.

Let’s look at some of the reasons why managers think synergies will be created. Sometimes, managers think that companies can, in a sense, “transfer” brand loyalty. This is completely impossible. For example, in the Pepsi/Frito Lay merger, it may make sense for logistics and economies of scale, but just because someone is loyal to Pepsi does not mean they will be loyal to Fritos. But, you can save money if the Pepsi and Fritos both go through the exact same logistics channels and therefore save on logistics expenditures.

Many times, businesses buy other companies because they think that the good management will transfer. Normally, in this situation, the buyers feel that there is an operational or management deficiency and that the M&A will somehow overcome this deficiency. This concept assumes that the buyer has accurately assessed the company and that the buyer has the right skills to turn around the company for a profit. This is largely like the idea of flipping houses without the predictability of the local market to give an investor some idea of the return on investment. This philosophy just doesn’t work. Just because a group of managers together makes good decisions and has a certain degree of luck in one business doesn’t mean that the luck and experience will transfer to the new company.

An acquisition can work, however, if the two companies are truly synergistic. For example, when JM Smucker bought Jif peanut butter from P&G, they created Uncrustables, the ready-made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. However, this brief example does not consider the fact that Smucker’s may have just been able to buy peanut butter from a supplier at a good price. So, even in this example, which seems to make complete sense, there is no way to know which move for JM Smucker would have ultimately been more profitable without the acquisition.

Christine Moorman showed in a 2011 marketing survey that of those companies that plan to grow (realize that excludes everyone who does not plan to grow), about 10 percent planned to grow through an acquisition and 14 percent through a partnership. Nearly 70 percent of the companies planned on organic growth.18 The reason for this is simple. M&As don’t work as often as we would like them to. The odds of a merger or acquisition working are high enough that companies will continue to try to make them work, but they are low enough that it is likely not the best growth strategy if the goal is long-term profitability. Generally, M&As are used as someone’s efforts to falsely boost a company’s earnings. This just doesn’t work. Beyond the fact that there is rarely added value, M&As frequently dilute a firm across more efforts and each individual product or service gets less attention.

ORGANIC GROWTH

The least wasteful growth strategy, if you desire to have growth, is organic growth. It leverages the capabilities of the company, serves current customers, and builds lasting relationships with new customers.

So, the solution to this common business waste is not to do it. If there is a company that seems like it makes sense to acquire, look to see if there is a true competitive advantage that company has in its industry that will increase the value of your current operations. Unless you can definitively show the ability to fix any operational problems in the company that you want to acquire, don’t pretend you or any consultant that you hire will be successful in getting the return on investment that you are assuming you will get from the deal.

![]() Note M&As rarely make financial sense. Do them only when there is a very obvious and exploitable synergy, like JM Smucker and Jif or Disney and Pixar.

Note M&As rarely make financial sense. Do them only when there is a very obvious and exploitable synergy, like JM Smucker and Jif or Disney and Pixar.

Waste from R&D

If you are developing your own products, you need to have effective research and development (R&D) to make good products that people want to purchase. If you make products for other companies developed by those companies, you need effective R&D to create efficient and effective processes. If you provide services to others, you need effective R&D to create processes that meet or exceed customer expectations. These points are rather obvious. With 70 percent of companies with a growth strategy of organic growth, as mentioned in Christine Moorman’s study, the R&D processes should be defined, if not done so already, and refined if in place. Unfortunately, there are many mistakes that can be made when doing R&D. In Chapter 3, we discuss more about market research in particular and statistics and analytics that go into understanding customer needs. Here, we focus on the overall process and some of the biggest areas of waste in R&D.

Process Mapping

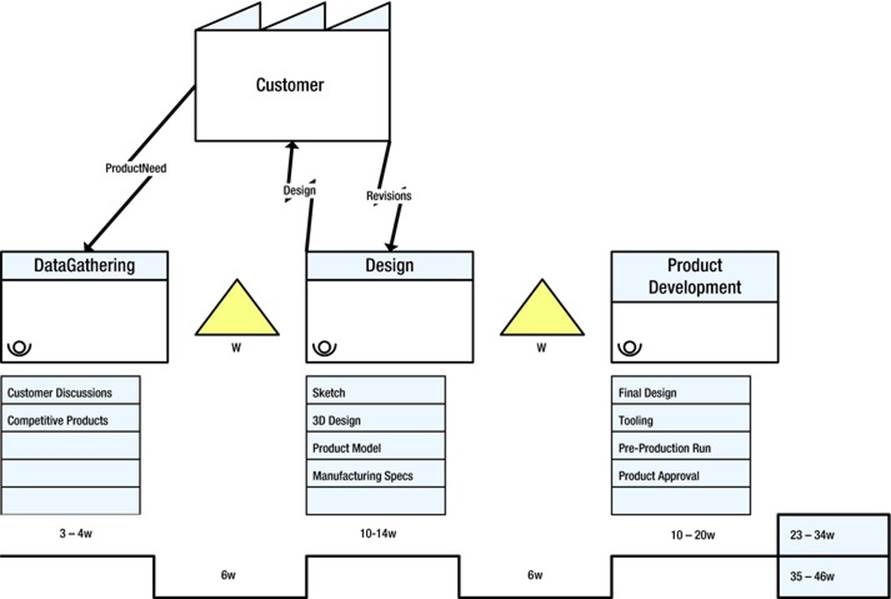

One of the biggest areas of waste in R&D is having no process at all. You should create a value stream process map for the R&D and innovative functions of your firm. With this, you can design and analyze the flow of information (mostly customer data), materials, and resources required to create new products, processes, or services. This allows you to gain a full picture of the total resources involved. Often, these are overlooked, like the total amount of each employee’s time in the project. By linking the process map to a Gantt chart, you can more easily recognize these connections. Likewise, by having a value-stream map of your R&D process, you can understand where the bottlenecks are and where the process is breaking down.

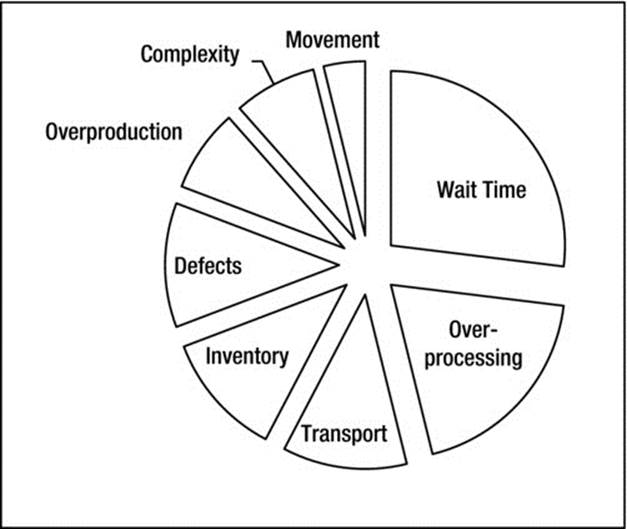

Process maps do not need to be complicated, but they need to be done. We provide an example of one in Figure 2-9. (This example is obviously a very simplified version of the development process. A real development process would have many, many more steps and resources associated with it.) Studies have shown that once process maps are put in place, one can expect to find 60–90 percent time waste in processes during new product development.19 The same study analyzed where typical waste occurs. The results are shown in Figure 2-10.

Figure 2-9. Sample Process Map

Figure 2-10. Areas of Waste in the R&D Process

This study found that the largest area of waste in product development came from waiting. This is defined as late delivery of information or delivery of information too early, which leads to rework. In order to overcome this area of waste, the R&D department should make sure that information is gathered from customer sources on time and be recent enough so that it is not obsolete. Most importantly, as soon as information is gathered, it should be processed and analyzed and entered into a database so that it can be readily found and accessed when needed. These databases should be available to everyone involved in the project, without layers of approval or delay.

Over-processing was identified as the next biggest area of waste in R&D. Excessive processing of information is defined as information processing beyond requirements. Waste in this area happens for many reasons, typically involving excessive formatting of reports because each person does not have a standard system. There is also a significant amount of over-processing due to lack of concurrent design processes and excessive approvals within the process. Turf wars often erupted when one department or person had a great idea or dataset, and did not want to share.

Transportation waste is defined as unnecessary movement of information between people, organizations, or systems. This area of waste is caused by the excess handling, reformatting, and re-entry of information. The more standardized systems are, the less the waste occurs. (We will spend time talking about these issues in Chapter 6, including how technology and IT systems can be developed to limit waste.)

Inventory waste occurs when information is unused. Think of this area almost as information overload. This waste occurs for many reasons. Sometimes people have a poor understanding of the project and its needs so they collect too much of the wrong information or there is a lack of disciplined systems for updating new information and purging old information. Defects create waste in the system typically because of human entry error or lack of validity and reliability checks of data. Overproduction occurs when information is over disseminated, typically when people send all information to everyone. Complexity occurs when the processes are overcomplicated. And finally, movement of information creates waste typically when people physically move information instead of using electronic means. This could happen because people print reports instead of using email or simply because of a bad physical distribution of people and resources.

Typically, when companies think about R&D and innovation, all they think about is how they can be more innovative. Yet, before this question is even asked, you should sit down and create a value stream map. This could save you 60–90 percent of your R&D staff’s time. Imagine how much more innovative you could be if you more than double your R&D resources!

![]() Note Stop worrying about how to be more innovative. Start worrying about how to make your R&D department more efficient, and then possibly double or triple your resources!

Note Stop worrying about how to be more innovative. Start worrying about how to make your R&D department more efficient, and then possibly double or triple your resources!

In addition to process-mapping the R&D department, there are a few more areas where businesses create waste. (Some of these are covered more in Chapter 3, along with some more detail on process-mapping your product-development process.)

Spaghetti on the Wall

We’re sure you’ve heard this expression. This is a common product-development strategy where the designers create dozens of concepts and pitch all the concepts internally or to existing customers until something is chosen. This is a horrible waste of resources! If you follow a sound process based upon good data gathered from customer sources, this won’t happen.

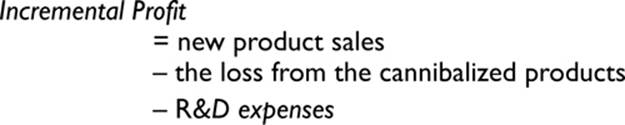

Product or Service Cannibalization

So you have a successful product or service that has gone through the natural lifecycle that all products go through. This product is near the end of its maturity and you want to get more sales. The natural inclination is to copy your successful products and “refresh” them, perhaps in a new color or a new version. After you create this new product and start selling it to your customers, you find that you have grown very little if at all. Why? You are cannibalizing your own products and driving your margins down. You are reducing efficiencies that you have built into your operation and are potentially building inventory that may be damaged or become obsolete.

This scenario can happen when you offer services as well. Maybe you introduce a new service or a new location and find minimal overall growth with increased costs. This is the result of the market being saturated by the fact that every company wants to grow.

Out of the thousands upon thousands of new products introduced every year, less than six percent featured any innovation in packaging, formulation, positioning, technology, market creation, or merchandising.20 That means that over 94 percent of new products and services were not actually new! That means there’s a 94 percent chance you are cannibalizing yourself! It is no wonder that over half of senior executives admit to being dissatisfied with the return of their new product innovations.21

To avoid waste, there should be extremely accurate, detailed forecasts of new and old product sales. (New product forecasting is outside the realm of this book, although we cover forecasting a bit in Chapter 7.) We highly recommend having a statistician with a marketing background on your staff or the help of consulting firm. This task should never be taken lightly. It should be done before launch as a forecast, and at many time intervals, post launch. The metric you are looking for here is incremental profit increase. To find that, you take new product sales, minus a loss from the cannibalized products, minus R&D expenses.

In most of these decisions, if you analyze your forecasts, losses, and expenses with sound statistics and analytics, you will find that more of the same is not an effective strategy. Instead, you need to find an unmet need or create a need through an innovative concept.

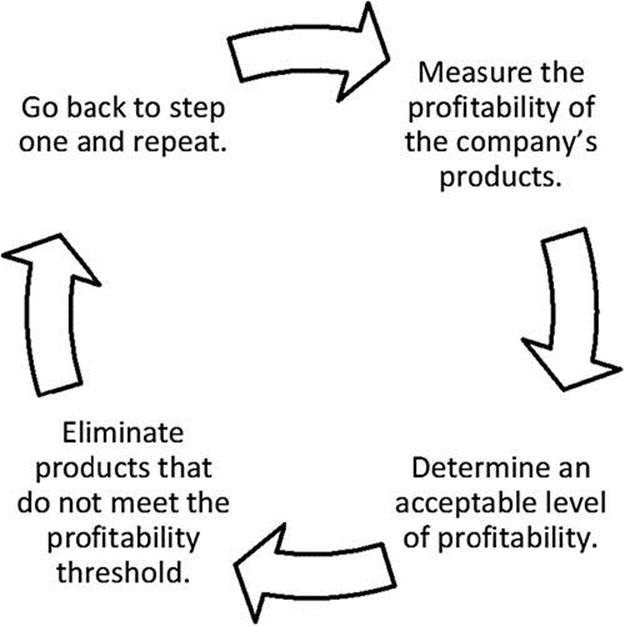

Don’t forget to consider the best way to eliminate bad products. The typical decision process to do this is shown in Figure 2-11. The rationale is fairly straightforward. If a product is no longer meeting a specified level of profitability, the company should eliminate it. This is very short-sided. It does not consider the customer’s needs and buying behavior.

Figure 2-11. What Not to Do When Eliminating Old Products

An example of how this process can go wrong is presented in the book Driving Customer Equity, by Rust and colleagues.22 They call this process the profitable product death spiral. Pretend that a grocery store ran an analysis and found out that high-end gourmet cheeses are extremely unprofitable. They carry price tags in the $10 to $30 range. They sit in the cooler, sometimes until they go bad. So, the grocery store manager decides to get rid of these cheeses. The next day, Sally is doing her grocery shopping. In addition to her normal shopping for the week, she is also shopping for her weekly Saturday night wine tasting party. As Sally fills up her cart with food, she goes to the wine department to select the wines for her party. Next, she makes a trip to the party section and picks out some lovely plates, paper napkins, and decorations for her party. She finally swings by the cheese section to get some cheeses to serve as appetizers with the wine. Imagine her frustration when her only options are mozzarella and cheddar. So, she checks out, leaves the store, and travels down the street to get her cheeses somewhere else.

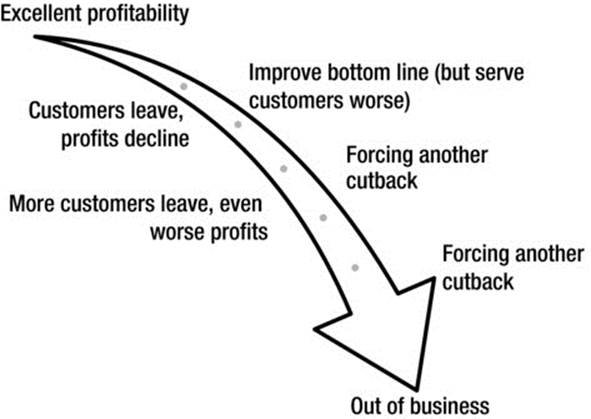

What is likely to happen next week on Sally’s shopping trip? Sally is busy. She doesn’t have time to run to two stores. So, the next week, she does all of her shopping at the store down the street. If she is consistently able to buy all of the products she needs at a good price, she will likely become loyal to the other store. Other customers will have the same buying pattern. An illustration is provided in Figure 2-12.

Figure 2-12. Profitable Product Death Spiral

What causes both cannibalization and the profitable product death spiral? You have to understand the buying behavior of customers at the individual level. You cannot rely on averages. Profitability comes from customers, not from products. The customers are paying your bills. You must set up information systems to track individual purchase decisions and behaviors. You need to understand complementary or competing products within your own company. (We give key metrics to understand this better in Chapter 3.) If you don’t understand this, your product decisions will likely be a waste.

Don’t Let Customers Design Your Products

That all being said, please realize a caveat. If you do supply a large retail company or industry giant, it is likely that you have experienced the request to design a product or service specifically for that retailer or giant, including changes to the packaging. If you believe that success is a result of differentiation and innovation, then what do you get when you take the brand and use it to become a custom manufacturer for the innovation of your customers? This is a classic issue that companies who sell to retailers face. In the name of growth, they create an environment where their products become commodities and where they are told what margin they will get for their products, how many they will create, and if they don’t sell, that they will be responsible for taking them back. It doesn’t take a business expert to know that the odds of long-term success in this business model are pretty slim. But, growth drives them to make these decisions. By the time they realize that they have made a mistake, the brand has been devalued. The customers who used to be willing to pay a higher price due to brand equity and quality are no longer willing to do so.

Use customer information to understand the market. Then, make decisions based upon your resources and abilities. You will never be all things to all people. You cannot forget your company’s strategic goals. If customer needs are forcing you to stray from your mission, you likely need to take another look at your goals and at the targeted customer niche.

Waste from Silos

The issue of organizational silos is discussed in several chapters in this book. They are one of the single most common roadblocks to efficiency. Many companies use resources to transfer funds between departments. Each department acts as its own business and must justify its budget and expenses. In order to make their departments look good, managers will create strategies around their own department’s profit and growth. Many times, departments will charge other departments for services. Process-improvement decisions are made based on the limited view of the manager’s span of control. Although this might be the most efficient way to run the department, in the end it costs the company money.

The customer experiences the whole company, not the individual departments, as explained in the previous wine and cheese example. In addition, if one department saves money, but causes an equivalent or greater cost in another area through that decision, it costs the organization money. This concept is also discussed in Chapter 7, but is worth mentioning here because at some point in any company’s history, this strategy was implemented. Most likely, this strategy is used to hold people accountable to meet the budget or ask only for interdepartmental services that have a real return on investment. This strategy is misguided because it makes employees care less about the overall health of the company and more about the health of their department. It sets up barriers to cross-functional work, which further degrades operational efficiencies.

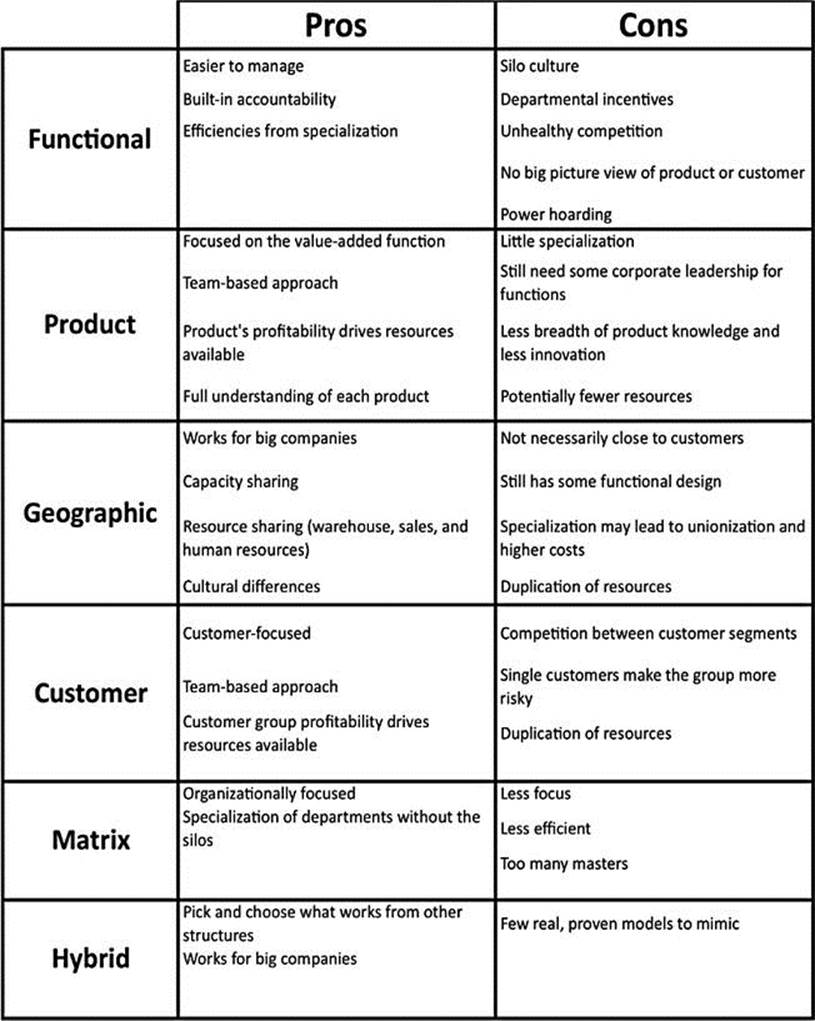

If we were to do a root cause analysis, we would find the issue of organizational structure a key problem to tackle. There are a few common options when looking at organizational structure:

· The functional design, the most common of the structures, has departments separated by what they do, such as human resources, finance, manufacturing, maintenance, engineering, nursing, marketing, and sales.

· The product design is when each product or product line has a group of the functions that you see in a functional design. This helps the employees focus on working together toward a common good rather than for their own department. However, you still end up with competition between product groups and you have duplication of resources.

· The geographic design features a group of entities structured around a geographic region that serves a specific customer base or product type. This typically is used in very large, spread out companies, or when geographic regions have very different needs.

· The customer design has groups that are focused on a single or small list of customers, where all of the functions have the same focus.

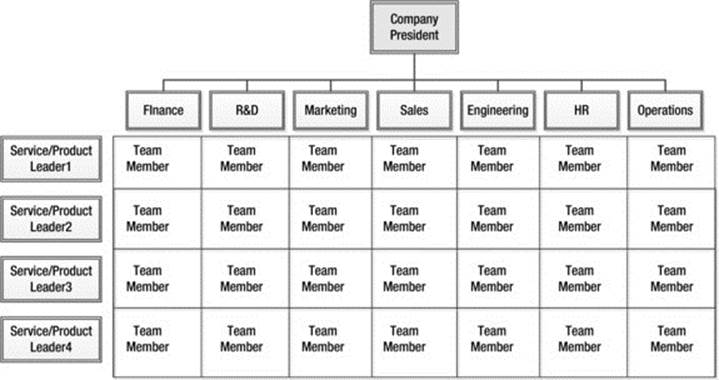

· The matrix design (Figure 2-13) is when there are more reporting relationships than single ones, and the structure may focus on the product, customer, or geographic type.

Figure 2-13. Matrix Organization

· The final structure is the hybrid design, which is some combination of the other designs.