Introduction to Game Design, Prototyping, and Development (2015)

Part I: Game Design and Paper Prototyping

Chapter 12. Puzzle Design

Puzzles are an important part of many digital games as well as an interesting design challenge in their own right. This chapter starts by exploring puzzle design through the eyes of one of the greatest living puzzle designers, Scott Kim.

The latter part of the chapter explores various types of puzzles that are common in modern games, some of which might not be what you would expect.

Puzzles Are Almost Everywhere

As you’ll learn through this chapter, most single-player games have some sort of puzzle in them. However, multiplayer games often do not. The primary reason for this is that both single-player games and puzzles rely on the game system to provide challenge to the player, where multiplayer digital games (that are not cooperative) more often rely on other human players to provide the challenge. Because of this parallel between single-player games and puzzles, learning about how to design puzzles will help you with any game that you intend to have a single-player or cooperative mode.

Scott Kim on Puzzle Design

Scott Kim is one of today’s leading puzzle designers. He has written puzzles for magazines such as Discover, Scientific American, and Games since 1990 and has designed the puzzle modes of several games including Bejeweled 2. He has lectured about puzzle design at both the TED conference and the Game Developers Conference. His influential full-day workshop, The Art of Puzzle Design1—which he delivered with Alexey Pajitnov (the creator of Tetris) at the 1999 and 2000 Game Developers Conferences—has shaped many game designers ideas about puzzles for over a decade. This chapter explores some of the content of that workshop.

1 Scott Kim and Alexey Pajitnov, “The Art of Puzzle Game Design” (presented at the Game Developers Conference, San Jose, CA, March 15, 1999), http://www.scottkim.com/thinkinggames/GDC99/index.html

What Is a Puzzle?

Kim states that his favorite definition of puzzle is also one of the simplest: “A puzzle is fun, and it has a right answer.”2 This differentiates puzzles from toys, which are fun but don’t have a right answer, and from games, which are fun but have a goal rather than a specific correct answer. Kim sees puzzles as separate from games, though I personally see them as more of a highly developed subset of games. Though this definition of puzzles is very simple, some important subtleties lie hidden therein.

2 Scott Kim, “What Is a Puzzle?” Accessed January 17, 2014, http://www.scottkim.com/thinkinggames/whatisapuzzle/.

A Puzzle Is Fun

Kim states that there are three elements of fun for puzzles:3

3 Ibid.

![]() Novelty: Many puzzles rely on a certain specific insight to solve them, and once the player has gained that insight, finding the puzzle’s solution is rather simple. A large part of the fun of solving a puzzle is that flash of insight, the joy of creating a new solution. If a puzzle lacks novelty, the player will often already have the insight required to solve it before even starting the puzzle, and thus that element of the puzzle’s fun is lost.

Novelty: Many puzzles rely on a certain specific insight to solve them, and once the player has gained that insight, finding the puzzle’s solution is rather simple. A large part of the fun of solving a puzzle is that flash of insight, the joy of creating a new solution. If a puzzle lacks novelty, the player will often already have the insight required to solve it before even starting the puzzle, and thus that element of the puzzle’s fun is lost.

![]() Appropriate difficulty: Just as games must seek to give the player an adequate challenge, puzzles must also be matched to the player’s skill, experience, and type of creativity. Each player approaching a puzzle will have a unique level of experience with puzzles of that type and a certain level of frustration that she is willing to experience before giving up. Some of the best puzzles in this regard have both an adequate solution that is of medium difficulty and an expert solution that requires advanced skill to discover. Another great strategy for puzzle design is to create a puzzle that appears to be simple though it is actually quite difficult. If the player perceives the puzzle to be simple, she’ll be less likely to give up.

Appropriate difficulty: Just as games must seek to give the player an adequate challenge, puzzles must also be matched to the player’s skill, experience, and type of creativity. Each player approaching a puzzle will have a unique level of experience with puzzles of that type and a certain level of frustration that she is willing to experience before giving up. Some of the best puzzles in this regard have both an adequate solution that is of medium difficulty and an expert solution that requires advanced skill to discover. Another great strategy for puzzle design is to create a puzzle that appears to be simple though it is actually quite difficult. If the player perceives the puzzle to be simple, she’ll be less likely to give up.

![]() Tricky: Many great puzzles cause the player to shift her perspective or thinking to solve them. However, even after having that perspective shift, the player should still feel that it will require skill and cunning to execute her plan to solve the puzzle. This is exemplified in the puzzle-based stealth combat of Klei Entertainment’s Mark of the Ninja, in which the player must use insight to solve the puzzle of how to approach a room full of enemies and then, once she has a plan, must physically execute that plan with precision.4

Tricky: Many great puzzles cause the player to shift her perspective or thinking to solve them. However, even after having that perspective shift, the player should still feel that it will require skill and cunning to execute her plan to solve the puzzle. This is exemplified in the puzzle-based stealth combat of Klei Entertainment’s Mark of the Ninja, in which the player must use insight to solve the puzzle of how to approach a room full of enemies and then, once she has a plan, must physically execute that plan with precision.4

4 Nels Anderson, “Of Choice and Breaking New Ground: Designing Mark of the Ninja” (presented at the Game Developers Conference, San Francisco, CA, March 29, 2013). Nels Anderson, the lead designer of Mark of the Ninja, spoke in this talk about narrowing the gulf between intent and execution. They found that making it easier for a player to execute on her plans in the game shifted the skill of the game from physical execution to mental planning, making the game more puzzle-like and more interesting to players. He has posted a link to his slides and his script for the talk on his blog at http://www.above49.ca/2013/04/gdc-13-slides-text.html, accessed March 6, 2014.

And It Has a Right Answer

Every puzzle needs to have a right answer, and some puzzles have several right answers. One of the key elements of a great puzzle is that once the player has found the right answer, it is clearly obvious to her that she is right. If the correctness of the answer isn’t easily evident, the puzzle can seem muddled and unsatisfying.

Genres of Puzzles

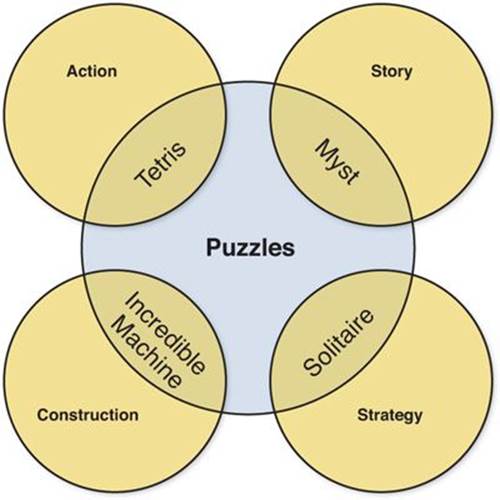

Kim identifies four genres of puzzle (see Figure 12.1),5 each of which causes the player to take a different approach and use different skills. These genres are at the point of intersection between puzzles and other activities. For example, a story puzzle is the mixture of a narrative and a series of puzzles.

5 Scott Kim and Alexey Pajitnov, “The Art of Puzzle Game Design,” slide 7.

![]() Action: Action puzzles like Tetris have time pressure and allow players a chance to fix their mistakes. They are the combination of an action game with a puzzle mindset.

Action: Action puzzles like Tetris have time pressure and allow players a chance to fix their mistakes. They are the combination of an action game with a puzzle mindset.

![]() Story: Story puzzles like Myst, the Professor Layton series, and most hidden-object games6 have puzzles that players must solve to progress through the plot and explore the environment. They combine narrative and puzzles.

Story: Story puzzles like Myst, the Professor Layton series, and most hidden-object games6 have puzzles that players must solve to progress through the plot and explore the environment. They combine narrative and puzzles.

6 Myst was one of the first CD-ROM adventure games, and was the number one best-selling CD-ROM game until The Sims took that title. The Professor Layton series of games is an ongoing series for Nintendo’s handheld platforms that wraps many individual puzzles inside an overarching mystery story. Hidden-object games are a popular genre of game where a player is given a list of objects to find hidden in a complicated scene. They often have mystery plots that they player is attempting to solve by finding the objects.

![]() Construction: Construction puzzles invite the player to build an object from parts to solve a certain problem. One of the most successful of these was The Incredible Machine, in which players built Rube Goldberg-like contraptions to cause the cats in each scene to run away. Some construction games even include a construction set that allows the player to devise and distribute her own puzzles. Construction puzzles are the intersection of construction, engineering, and spatial reasoning with puzzles.

Construction: Construction puzzles invite the player to build an object from parts to solve a certain problem. One of the most successful of these was The Incredible Machine, in which players built Rube Goldberg-like contraptions to cause the cats in each scene to run away. Some construction games even include a construction set that allows the player to devise and distribute her own puzzles. Construction puzzles are the intersection of construction, engineering, and spatial reasoning with puzzles.

![]() Strategy: Many strategy puzzle games are the solitaire versions of the kinds of puzzles that players encounter in games that are traditionally multiplayer. These include things like bridge puzzles (which present players with various hands in a bridge game and ask how play should proceed) and chess puzzles (which give players a few chess pieces positioned on a board and ask how the player could achieve checkmate in a certain number of moves). These combine the thinking required for the multiplayer version of the game with the skill building of a puzzle to help players train to be better at the multiplayer game.

Strategy: Many strategy puzzle games are the solitaire versions of the kinds of puzzles that players encounter in games that are traditionally multiplayer. These include things like bridge puzzles (which present players with various hands in a bridge game and ask how play should proceed) and chess puzzles (which give players a few chess pieces positioned on a board and ask how the player could achieve checkmate in a certain number of moves). These combine the thinking required for the multiplayer version of the game with the skill building of a puzzle to help players train to be better at the multiplayer game.

Figure 12.1 Kim’s four genres of puzzles7

7 Scott Kim and Alexey Pajitnov, “The Art of Puzzle Game Design,” slide 7.

Kim also holds that there are some pure puzzles that don’t fit in any of the other four genres. This would include things like Sudoku or crossword puzzles.

The Four Major Reasons that People Play Puzzles

Kim’s research and experience have led him to believe that people primarily play puzzles for the following reasons:8

8 Scott Kim and Alexey Pajitnov, “The Art of Puzzle Game Design,” slide 8.

![]() Challenge: People like to feel challenged and to feel the joy of overcoming those challenges. Puzzles are an easy way for players to feel a sense of achievement, accomplishment, and progress.

Challenge: People like to feel challenged and to feel the joy of overcoming those challenges. Puzzles are an easy way for players to feel a sense of achievement, accomplishment, and progress.

![]() Mindless distraction: Some people seek big challenges, but others are more interested in having something interesting to do to pass the time. Several puzzles like Bejeweled and Angry Birds don’t provide the player with a big challenge but rather a low-stress interesting distraction. Puzzle games of this type should be relatively simple and repetitive rather than relying on a specific insight (as is common in puzzles played for challenge).

Mindless distraction: Some people seek big challenges, but others are more interested in having something interesting to do to pass the time. Several puzzles like Bejeweled and Angry Birds don’t provide the player with a big challenge but rather a low-stress interesting distraction. Puzzle games of this type should be relatively simple and repetitive rather than relying on a specific insight (as is common in puzzles played for challenge).

![]() Character and environment: People like great stories and characters, beautiful images, and interesting environments. Puzzle games like Myst, The Journeyman Project, the Professor Layton series, and The Room series rely on their stories and art to propel the player through the game.

Character and environment: People like great stories and characters, beautiful images, and interesting environments. Puzzle games like Myst, The Journeyman Project, the Professor Layton series, and The Room series rely on their stories and art to propel the player through the game.

![]() Spiritual journey: Finally, some puzzles mimic spiritual journeys in a couple of different ways. Some famous puzzles like Rubik’s Cube can be seen as a rite of passage—either you’ve solved one in your life or you haven’t. Many mazes work on this same principle. Additionally, puzzles can mimic the archetypical hero’s journey:9 the player starts in regular life, encounters a puzzle that sends her into a realm of struggle, fights against the puzzle for a while, gains an epiphany of insight, and then can easily defeat the puzzle that had stymied her just moments earlier.

Spiritual journey: Finally, some puzzles mimic spiritual journeys in a couple of different ways. Some famous puzzles like Rubik’s Cube can be seen as a rite of passage—either you’ve solved one in your life or you haven’t. Many mazes work on this same principle. Additionally, puzzles can mimic the archetypical hero’s journey:9 the player starts in regular life, encounters a puzzle that sends her into a realm of struggle, fights against the puzzle for a while, gains an epiphany of insight, and then can easily defeat the puzzle that had stymied her just moments earlier.

9 The concept of the hero’s journey was presented by Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Campbell’s theory is that there is a single monomyth that is shared by all cultures of a young person leaving the world that is comfortable to her, experiencing trials and diffi culties, overcoming a great foe, and then returning to her home with the skills to lead her people to new heights. (The hero’s journey traditionally focuses exclusively on male protagonists, but there’s no reason to continue that gender bias.)

Modes of Thought Required by Puzzles

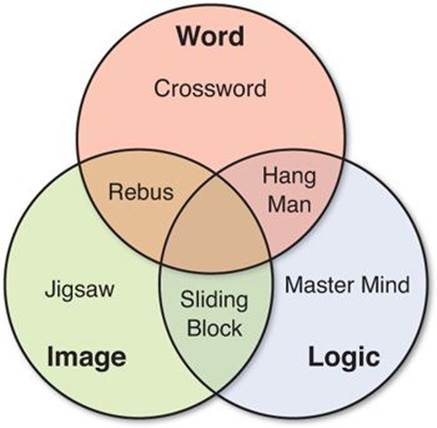

Puzzles require players to think in different ways to solve them, and most players have a particular mode of thought that they prefer to engage in (and therefore a favorite class of puzzle). Figure 12.2 illustrates these concepts, and the list that follows explains each mode.

Figure 12.2 The modes of thought that Scott Kim has found are often used in puzzles including examples of each mode and of puzzles that use two modes of thought simultaneously10

10 Scott Kim and Alexey Pajitnov, “The Art of Puzzle Game Design.” Slide 9.

![]() Word: There are many different kinds of word puzzles. Most rely on the player having a large and varied vocabulary.

Word: There are many different kinds of word puzzles. Most rely on the player having a large and varied vocabulary.

![]() Image: Image puzzle types include jigsaw, hidden-object, and 2D/3D spatial puzzles. Image puzzles tend to exercise the parts of the brain connected to visual/spatial processing and pattern recognition.

Image: Image puzzle types include jigsaw, hidden-object, and 2D/3D spatial puzzles. Image puzzles tend to exercise the parts of the brain connected to visual/spatial processing and pattern recognition.

![]() Logic: Logic puzzles like Master Mind/Bulls & Cows (described in Chapter 11, “Math and Game Balance”), riddles, and deduction puzzles cause the player to exercise their logical reasoning. Many games are based on deductive reasoning: the top-down elimination of several false possibilities, leaving only one that is true (e.g., a player reasoning “I know that all of the other suspects are innocent, so Colonel Mustard must have killed Mr. Boddy”). These include Clue, Bulls & Cows, and Logic Grid puzzles. There are far fewer games that use inductive reasoning: the bottom-up extrapolation from a specific certainty to a general probability (e.g., a player reasoning “The last five times that John bluffed in Poker, he habitually scratched his nose; he’s scratching his nose now, so he’s probably bluffing”). Deductive logic leads to certainty, while inductive logic makes an educated guess based on reasonable probability. The certainty of the answers has traditionally made deductive logic more attractive to puzzle designers.

Logic: Logic puzzles like Master Mind/Bulls & Cows (described in Chapter 11, “Math and Game Balance”), riddles, and deduction puzzles cause the player to exercise their logical reasoning. Many games are based on deductive reasoning: the top-down elimination of several false possibilities, leaving only one that is true (e.g., a player reasoning “I know that all of the other suspects are innocent, so Colonel Mustard must have killed Mr. Boddy”). These include Clue, Bulls & Cows, and Logic Grid puzzles. There are far fewer games that use inductive reasoning: the bottom-up extrapolation from a specific certainty to a general probability (e.g., a player reasoning “The last five times that John bluffed in Poker, he habitually scratched his nose; he’s scratching his nose now, so he’s probably bluffing”). Deductive logic leads to certainty, while inductive logic makes an educated guess based on reasonable probability. The certainty of the answers has traditionally made deductive logic more attractive to puzzle designers.

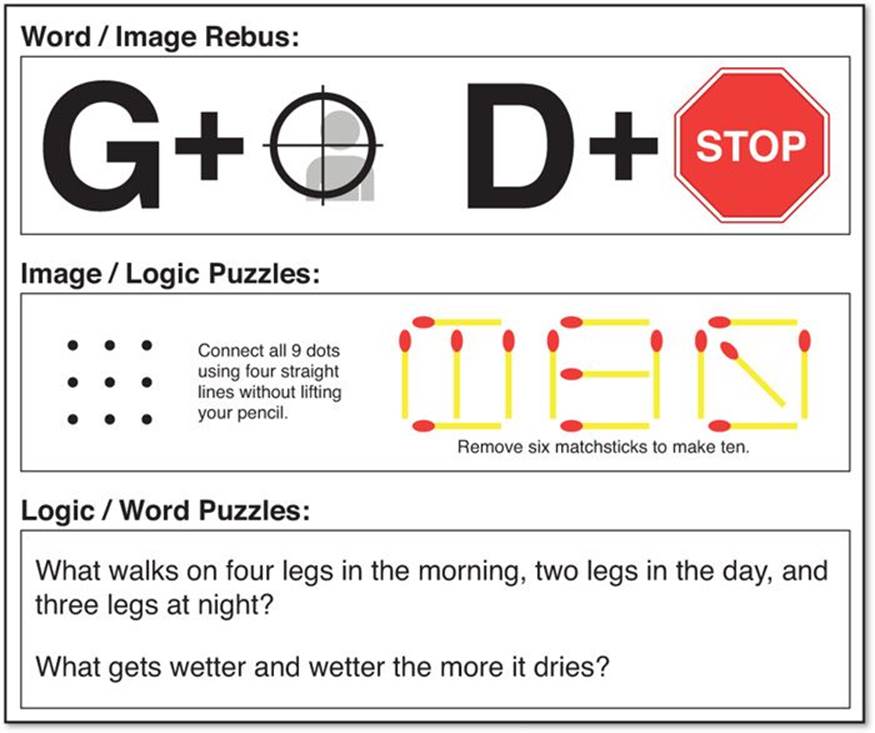

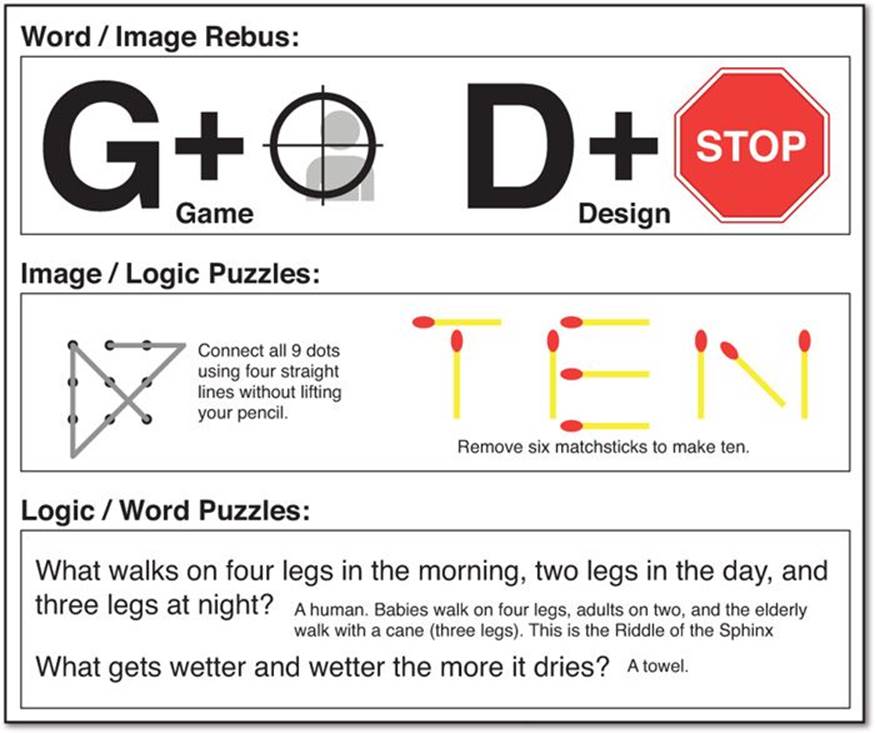

![]() Word/Image: Many games like Scrabble, rebuses (like the one in Figure 12.3), and word searches incorporate both the word and image modes of thought to solve. Scrabble is a mixed-mode puzzle, but crossword puzzles are not, because in Scrabble the player is determining where to place the word and attempting to arrange it over score multipliers on the board. These are two acts of visual/spatial reasoning and decision-making that are not needed to play a crossword puzzle.

Word/Image: Many games like Scrabble, rebuses (like the one in Figure 12.3), and word searches incorporate both the word and image modes of thought to solve. Scrabble is a mixed-mode puzzle, but crossword puzzles are not, because in Scrabble the player is determining where to place the word and attempting to arrange it over score multipliers on the board. These are two acts of visual/spatial reasoning and decision-making that are not needed to play a crossword puzzle.

Figure 12.3 Various mixed-mode puzzles (solutions are at the end of the chapter)

![]() Image/Logic: Sliding block puzzles, laser mazes, and puzzles like those shown in the second category of Figure 12.3 fit this category.

Image/Logic: Sliding block puzzles, laser mazes, and puzzles like those shown in the second category of Figure 12.3 fit this category.

![]() Logic/Word: Most riddles fall into this category, including the classic Riddle of the Sphinx, which is the first riddle in Figure 12.3. It was given by the sphinx to Oedipus in the classic Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex by Sophocles.

Logic/Word: Most riddles fall into this category, including the classic Riddle of the Sphinx, which is the first riddle in Figure 12.3. It was given by the sphinx to Oedipus in the classic Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex by Sophocles.

Kim’s Eight Steps of Digital Puzzle Design

Scott Kim describes eight steps that he typically goes through when designing a puzzle:11

11 Scott Kim and Alexey Pajitnov, “The Art of Puzzle Game Design,” slide 97.

1. Inspiration: Just like a game, inspiration for a puzzle can come from anywhere. Alexey Pajitnov has stated that his inspiration for Tetris was the mathematician Solomon Golomb’s concept of pentominoes (12 different shapes, each made of five blocks, that could be fit together into an optimal space-filling puzzle) and the desire to use them in an action game. However, there were too many different five-block pentomino shapes, so he reduced it to the seven four-block tetrominoes found in Tetris.

2. Simplification: Usually you need to go through some form of simplification to get from your original inspiration to a playable puzzle.

a. Identify the core puzzle mechanic, the essential tricky skill required.

b. Eliminate any irrelevant details; narrow the focus.

c. Make pieces uniform. For example, if you’re dealing with a construction puzzle, move the pieces onto a uniform grid to make it easier for the player to manipulate.

d. Simplify the controls. Make sure that the controls for the puzzle are appropriate to the interface. Kim talks about how great a Rubik’s Cube feels in real life but how terrible it would be to manipulate a digital version with a mouse and keyboard.

3. Construction set: Build a tool that makes construction of puzzles quick and easy. Many puzzles can be built and tested as paper prototypes, but if that isn’t the case for your puzzle, this is the first place that you will need to do some programming. Regardless of whether it is paper or digital, an effective construction set can make the creation of additional levels much, much easier for you. Determine which tasks are repetitive time-wasters in the puzzle construction process and see if you can’t make reusable parts or automated processes for them.

4. Rules: Define and clarify the rules. This includes defining the board, the pieces, the ways that they can move, and the ultimate goal of the puzzle or level.

5. Puzzles: Make some levels of the puzzle. Make sure that you create different levels that explore various elements of your design and game mechanics.

6. Testing: Just like a game, you don’t know how players will react to a puzzle until you place it in front of them. Even with his many years of experience, Kim still finds that some puzzles he expects to be simple are surprisingly difficult, while some he expects to be difficult are easily solved. Playtesting is key in all forms of design. Usually, step 6 leads the designer to iteratively return to steps 4 and 5 and refine previous decisions.

7. Sequence: Once you have refined the rules of the puzzle and have several levels designed, it’s time to put them in a meaningful sequence. Every time you introduce a new concept, it should be done in isolation, requiring the player to use just that concept in the most elementary way. Then you can progressively increase the difficulty of the puzzle that must be solved using that concept. Finally, you can create puzzles that mix that concept with other concepts that the player already understands. This is very similar to the sequencing in Chapter 13, “Guiding the Player,” that is recommended for teaching any new game concept to a player.

8. Presentation: With the levels, rules, and sequence all created, it’s now time to refine the look of the puzzle. Presentation also includes refinements to the interface and to the way that information is displayed to the player.

Seven Goals of Effective Puzzle Design

You need to keep several things in mind when designing a puzzle. Generally, the more of these goals that you can meet, the better puzzle you will create:

![]() User friendly: Puzzles should be familiar and rewarding to their players. Puzzles can rely on tricks, but they shouldn’t take advantage of the player or make the player feel stupid.

User friendly: Puzzles should be familiar and rewarding to their players. Puzzles can rely on tricks, but they shouldn’t take advantage of the player or make the player feel stupid.

![]() Ease of entry: Within one minute, the player must understand how to play the puzzle. Within a few minutes, the player should be immersed in the experience.

Ease of entry: Within one minute, the player must understand how to play the puzzle. Within a few minutes, the player should be immersed in the experience.

![]() Instant feedback: The puzzle should be “juicy” in the way that Kyle Gabler (co-creator of World of Goo and Little Inferno) uses the word:12 The puzzle should actively react to player input in a way that feels physical, active, and energetic.

Instant feedback: The puzzle should be “juicy” in the way that Kyle Gabler (co-creator of World of Goo and Little Inferno) uses the word:12 The puzzle should actively react to player input in a way that feels physical, active, and energetic.

12 Kyle Gray, Kyle Gabler, Shalin Shodan, and Matt Kucic. “How to Prototype a Game in Under 7 Days” Accessed May 29, 2014. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/130848/how_to_prototype_a_game_in_under_7_.php

![]() Perpetual motion: The player should constantly be prodded to take the next step, and there should be no clear stopping point. When I worked at Pogo.com, all of our games ended with a Play Again button instead of a game over screen. Even a simple thing like that can keep players playing for longer.

Perpetual motion: The player should constantly be prodded to take the next step, and there should be no clear stopping point. When I worked at Pogo.com, all of our games ended with a Play Again button instead of a game over screen. Even a simple thing like that can keep players playing for longer.

![]() Crystal-clear goals: The player should always clearly understand the primary goal of the puzzle. However, it’s also useful to have advanced goals for players to discover over time. The puzzle games Hexic and Bookworm are examples of puzzles that have very clear initial goals and also include advanced expert goals that veteran players can discover over time.

Crystal-clear goals: The player should always clearly understand the primary goal of the puzzle. However, it’s also useful to have advanced goals for players to discover over time. The puzzle games Hexic and Bookworm are examples of puzzles that have very clear initial goals and also include advanced expert goals that veteran players can discover over time.

![]() Difficulty levels: The player should be able to engage the puzzle at a level of difficulty that is appropriate to her skill. Just like all games, appropriate difficulty is critical to making the experience fun for players.

Difficulty levels: The player should be able to engage the puzzle at a level of difficulty that is appropriate to her skill. Just like all games, appropriate difficulty is critical to making the experience fun for players.

![]() Something special: Most great puzzle games include something that makes them unique and interesting. Alexey Pajitnov’s game Tetris combines apparent simplicity with the chance for deep strategy and steadily increasing intensity. Both World of Goo and Angry Birds have incredibly juicy, reactive gameplay.

Something special: Most great puzzle games include something that makes them unique and interesting. Alexey Pajitnov’s game Tetris combines apparent simplicity with the chance for deep strategy and steadily increasing intensity. Both World of Goo and Angry Birds have incredibly juicy, reactive gameplay.

Puzzle Examples in Action Games

There are a huge number of puzzles within modern AAA game titles. Most of these fall into one of the following categories.

Sliding Block / Position Puzzles

These puzzles usually take place in third-person action games and require the player to move large blocks around a gridded floor to create a specific pattern. An alternative version of this used in some games involves positioning mirrors that are used to bounce light or laser beams from a source to a target. One variation that is commonly introduced is a slippery floor that causes the blocks to move continuously until they hit a wall or other obstacle.

![]() Game examples: Soul Reaver, Uncharted, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, Tomb Raider, The Legend of Zelda

Game examples: Soul Reaver, Uncharted, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, Tomb Raider, The Legend of Zelda

Physics Puzzles

These puzzles all involve using the physics simulation built in to the game to move objects around the scene or hit various targets with either the player character or other objects. This is the core mechanic in the Portal series and has become increasingly popular as reliable physics engines like Havok and the Nvidia PhysX system (built in to Unity) have become ubiquitous in the industry.

![]() Game examples: Portal, Half-Life 2, Super Mario Galaxy, Rochard, Angry Birds

Game examples: Portal, Half-Life 2, Super Mario Galaxy, Rochard, Angry Birds

Traversal

These puzzles show you a place in the level that you need to reach but often make it less than obvious how to get there. The player must frequently take detours to unlock gates or open bridges that will allow her to reach her objective. Racing games like Gran Turismo can also be seen as traversal puzzles; the player must discover the perfect racing line that will enable her to complete each lap as efficiently and quickly as possible. This is critically important in the Burning Lap puzzles of the Burnout series in which players are asked to traverse a racecourse that includes sections of oncoming traffic and hairpin turns without making a single mistake.

![]() Game examples: Uncharted, Tomb Raider, Assassin’s Creed, Oddworld: Abe’s Oddyssee, Gran Turismo, Burnout, Portal

Game examples: Uncharted, Tomb Raider, Assassin’s Creed, Oddworld: Abe’s Oddyssee, Gran Turismo, Burnout, Portal

Stealth

An extension of traversal puzzles that became important enough to merit its own genre, stealth puzzles ask the player to traverse a level while also avoiding detection by enemy characters, who are usually patrolling a predetermined path or following a specific schedule. Players usually have a way to disable the enemy characters, though this can also lead to detection if performed poorly.

![]() Game examples: Metal Gear Solid, Uncharted, Oddworld: Abe’s Oddyssee, Mark of the Ninja, Fallout 3, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, Assassin’s Creed

Game examples: Metal Gear Solid, Uncharted, Oddworld: Abe’s Oddyssee, Mark of the Ninja, Fallout 3, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, Assassin’s Creed

Chain Reaction

These games include physics systems in which various components can interact, often to create explosions or other mayhem. Players use their tools to set traps or series of events that will either solve a puzzle or gain them an advantage over attacking enemies. The Burnout series of racing games include a Crash Mode that is a puzzle game where the player must drive her car into a specific traffic situation and cause the greatest amount of monetary damage through a fantastic multicar collision.

![]() Game examples: Pixel Junk Shooter, Tomb Raider (2013), Half-Life 2, The Incredible Machine, Magicka, Red Faction: Guerilla, Far Cry 2, Bioshock, Burnout

Game examples: Pixel Junk Shooter, Tomb Raider (2013), Half-Life 2, The Incredible Machine, Magicka, Red Faction: Guerilla, Far Cry 2, Bioshock, Burnout

Boss Fights

Many boss fights, especially in classic games, involve some sort of puzzle where the player is required to learn the pattern of reactions and attacks used by a boss and determine a series of actions that exploit this pattern to defeat the boss. This is especially common in third-person action games by Nintendo like those in the Zelda, Metroid, and Super Mario series. One element that is very common in this kind of puzzle is the rule of three: The first time the player performs the correct action to damage the boss, it is often a surprise to her, the second time, she is experimenting to see if she now has the insight to defeat the puzzle/boss, and the third time, she is demonstrating her mastery over the puzzle and defeats the boss. Most bosses throughout the Legend of Zelda series since The Ocarina of Time can be defeated in three attacks, as long as the player understands the solution to the puzzle of that boss.

![]() Game examples: The Legend of Zelda, God of War, Metal Gear Solid, Metroid, Super Mario 64/Sunshine/Galaxy, Guacamelee, Shadow of the Colossus, multiplayer cooperative raids in World of Warcraft

Game examples: The Legend of Zelda, God of War, Metal Gear Solid, Metroid, Super Mario 64/Sunshine/Galaxy, Guacamelee, Shadow of the Colossus, multiplayer cooperative raids in World of Warcraft

Summary

As you’ve seen in this chapter, puzzles are an important aspect of many games that have single-player modes. As a game designer, puzzle design is not a large departure from the skills you’ve already learned, but there are some subtle differences. When designing a game, the most important aspect is the moment-to-moment gameplay, whereas in puzzle design, the solution and the moment of insight are of primary importance. (In an action puzzle like Tetris, however, insight and solution happen with the drop and placement of every piece.) In addition, when the player solves a puzzle, it is important that she can tell that she has found the right answers; in games interesting decisions rely on there being uncertainty in the player’s mind about the outcome or correctness of decisions.

Regardless of the differences between designing puzzles and games, the iterative design process is as critical for puzzles as it is for all other kinds of interactive experiences. As a puzzle designer, you will want to make prototypes and playtest just as you would for a game; however, with puzzles, it is even more critical that your playtesters have not seen the puzzle before (because they will have already had the moment of insight).

To close, Figure 12.4 shows the solutions to the puzzles in Figure 12.3. I didn’t want to give away the answer by saying so, but the insight of the matchstick puzzle is that it actually requires all three modes of thought: logic, image, and word.

Figure 12.4 Mixed-mode puzzle solutions for the puzzles shown in Figure 12.4