Supplier Relationship Management: How to Maximize Vendor Value and Opportunity (2014)

Chapter 6. “Problem Children”

Addressing Problematic Supplier Relationships

From a psychological point of view, children are often called problem children if they are not able to manage everyday challenges and problems, or if they are not performing as expected in their environment.

It is already a given in science that problem children are not always suffering from a disease; on the contrary, these children often tend to be highly intelligent. It is important to understand the real root causes. They are not able to show their potential because they are not challenged and valued enough. Their capabilities need to be fostered and promoted. They need support and should be sponsored to perform successfully.

The other case that occurs is that these problem children are just too slow to keep up with their peer group. Sometimes this is just because of laziness.

It is really difficult for parents to distinguish which group the child belongs in—and determining that is exactly the art in the diagnosis. The same principles are true for the bottom group in the supplier interaction matrix, Mitigate, Develop, and Bail Out.

Suppliers in each of these models have important characteristics in common:

1. Their current performance is very low.

2. They need significant care and risk management.

The analogy to the children just mentioned holds here as well: some are lazy, some are having real problems, and some are super smart but choosing not to show their capabilities. Yet you must be able to assess the strategic value that the supplier brings. This is the key challenge. Is the supplier the highly intelligent child, with great innovations or new technologies used on behalf of their client companies but just overstrained in daily business? In this case, considering this supplier a Bail Out would make sense to utilize the strategic potential as competitive advantage. If the performance of a well-known supplier with very limited strategic potential is sluggish, then tagging that supplier a Mitigate is the answer. The supplier needs to understand that either it improves and rises to the occasion or it is out. If we find that a supplier has performance somewhere in between low and high strategic potential, then Develop could be the best interaction model to place it in. This would mean that the supplier will be nurtured so as to perform more effectively.

The competitive advantage of successful companies—just as with successful psychologists—is that they identify very fast which type of problem child they have in front of them and they make immediate, rigorous decisions on the way forward.

Characteristics of Mitigate Suppliers

Mitigate is an area of the SRM framework where we normally find around 5 percent of all suppliers. For a company with 1,000 suppliers, we would accordingly expect to find dozens of suppliers in this interaction model.

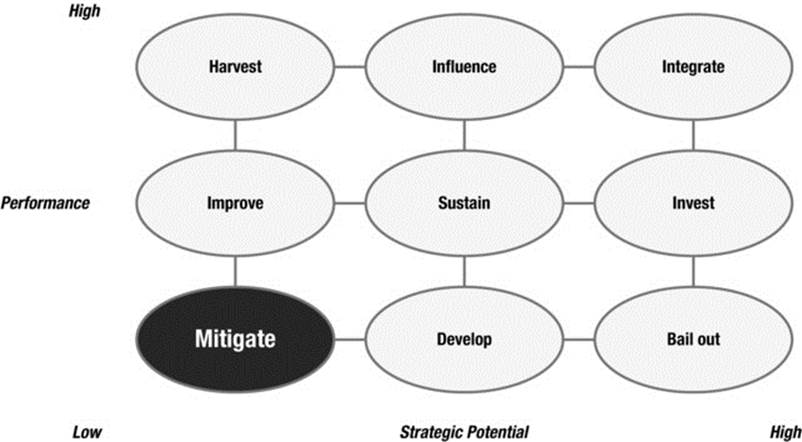

In general, suppliers in Mitigate (Figure 6-1) have low strategic potential. The products and services they provide represent no clear differentiating factor for the company’s position in the market. While the majority of suppliers share this characteristic, those in Mitigate need much closer attention than those in Improve or Harvest.

Figure 6-1. Mitigate suppliers

The lack of strategic potential is not the most critical aspect that requires application of the “up or out” rule. The real challenge is that Mitigate suppliers have severe performance issues. Delivery, cost, and/or quality show permanent shortcomings over time. This is why the downside potential with such suppliers is tremendous. We find this position in all sorts of suppliers. Quite often, they are large suppliers with commoditized products and may even be long-lasting relationships. The overall attention that the supplier gives you decreases, however, as they pursue and acquire emerging new customers. Alternatively, they just become complacent.

Based on the low strategic value and poor performance, there is an immediate need for action. The supplier needs to understand it has to improve performance—to move “up”—or it will be replaced—moved “out.” This is why a solid contingency plan for replacement is an integrated element of this interaction model.

Needless to say, a large portion of risk management is closely linked with this area of SRM. This is done to mitigate both the consequences of poor performance and the dislocation issues associated with replacement.

What Kind of Behavior to Drive

While most of the other interaction models have one clear desired behavior, there are a couple of options in this case. Specifically, we need to distinguish between the up behavior and the out behavior for the supplier. The supplier commonly needs to understand the necessity for changing its behavior and the consequences related to it. Of course, the most desired behavior for Mitigate is a supplier that improves and delivers a solid performance and improves shortcomings in a very short period of time without the company’s involvement. But what if the supplier either fails or is not willing to improve, and so needs to be replaced?

In that case, the desired behavior is for the supplier to remain professional, transparent, and open in the replacement and in the transition period. At least some of the performance issues need to be stabilized, requiring some short-term fixes. Some significant oversight by the company is necessary in the replacement phase—on the one hand to fix the issues for the next supplier and on the other hand to ensure a smooth transition.

Paradoxically, the quality of such a relationship—even though it is ending—is one of the most important ones in SRM because you need to maintain a level of openness and clarity while you are still working together.

![]() Note When you have decided to switch to a different supplier, you and the incumbent both need to operate with clarity and good intentions. When a supplier knows it is being edged out, that’s not the easiest situation to handle for either party.

Note When you have decided to switch to a different supplier, you and the incumbent both need to operate with clarity and good intentions. When a supplier knows it is being edged out, that’s not the easiest situation to handle for either party.

How to Work with Mitigate Suppliers

Suppliers in Mitigate are given a final chance to improve, but there will be very limited guidance because they are simply not worth the effort. The dissatisfaction with the supplier needs to be communicated and fact based. The supplier needs to clearly understand how serious the situation is. Then, you give it an opportunity to improve. If they do not take it, you need to move them out.

While the up portion of this interaction model is very much about suppliers improving performance on their own, the challenge is the out portion. The main ingredient to being successful in this interaction model is transparency. You especially need to understand interdependencies across different lines of business/business units or within different categories. The impact of bringing in a potential replacement needs to be intelligently evaluated. Be aware that, for example, some of the supporting processes or services of the supplier are not always obvious. A potential exit needs to be aligned and supported by stakeholders. Guidance for this alignment will most probably be scenarios, business cases, and contingency plans based on an anticipated supplier reaction.

For example, you need to be prepared for the supplier to become even less focused on your needs in this period. The team that has currently been serving your needs within the organization may gravitate to different customers, for example. Performance may degrade still further. You need to be prepared for these eventualities and be able to ramp up a replacement option more quickly than originally expected.

Once the supplier receives word of the transition, your desire is that this will fulfill all remaining business obligations and articulate steps for handing off the business to a new supplier rather than create problems. Typically, you would agree on a joint transition plan that will be executed by the supplier being replaced in cooperation with the new supplier. Usually, suppliers manage exits professionally. It is bad for their reputation to cause intentional problems. Issues tend to be most likely when the supplier being replaced is relatively small and is either captive to you or has a small number of customers in total. In this situation, the supplier’s wider reputation is less important for it and it has more to lose by being replaced. The risk of a tricky exit is consequently higher.

Once the transition plan is in place and being executed, the most important—but also the most difficult—success factor in the transition is to remain professional. Displays of emotions on both the supplier and the buyer side are inappropriate. Be sure to get a view on the supplier’s inner state; the supplier needs to be as transparent as a pane of glass.

Last but not least, it is key not to leave a battlefield behind. Keep the relationship alive with a view for future business. Usually, the supplier will be keen to do this, too.

Governance

As each company has dozens of suppliers in Mitigate, we have to distinguish between the effort related to Mitigate in the up and the out sections. As we have already discussed, the positioning of a supplier in Mitigate can become really critical for the company and fast actions need to be readied. In most cases, there is no time to wait for a quarterly or annual review meeting. You need to get into contact with the supplier once the shortcomings are realized. The purpose will be to ask the supplier to provide a mitigation plan against which its performance improvement will be measured.

In those cases where the supplier is not able to realize an up, the transition comes into place. In the transition, it is key to ask the supplier to update you on every aspect of the phasing out. Depending on the scope and the expected time of replacement, it makes sense to have regular meetings with the supplier just as you would with a state-of-the-art project management team. This encompasses aspects such as achievements to date, identified obstacles, problems, and mitigation planning. Most meetings of this type only take place between the existing supplier and the client, but it turns out to be much more effective if the new supplier is involved, too. Supplier facilities, inventory levels, order volumes, or quality fulfillments need to be monitored closely as part of integrated risk management during the implementation. If severe problems occur during the transition, a task force has to be put in place at the supplier to secure supply.

Case Example

When you had your last yogurt, did you think about the complexity of the box and the lid? Probably not. Nevertheless, a yogurt lid is something quite interesting and manufacturing one could cause a lot of trouble with the supplier. Some background on the lid: the structure is mainly based on aluminum, printing ink, lacquers, and a layer of varnish.

Varnish is a mostly glossy or semiglossy, transparent finish that is used to protect and to finish. It normally has no color pigments in it. Ingredients of varnishes are kept highly confidential. In general, their production is not a rocket science and the type of varnish used is in most cases not a differentiating factor. End customers do not even know that there are different varieties. What’s more, the yogurt producers do not care about the varnish producer. The varnish is supplied to a flexible packaging manufacturer that then supplies the yogurt producer. So, is the varnish quite a simple product? Is it then easy to change varnish suppliers? Not risky at all?

Generally speaking, for varnishes this is true, but it is much more complicated if you look further into this specific case. In yogurts, the varnish has contact with food, and as some people tend to have the habit to lick the yogurt from the lid, they are also in direct contact with the varnish, meaning that the varnish needs to have FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) approval. The FDA’s approvals of the products it regulates are as varied as the products themselves. These differences are dictated by the laws the FDA enforces and the relative risks that the products pose to consumers. Beside FDA approval, another thing to know is that varnishes show different reactions over time. Even with sophisticated laboratory methods, it is not possible to simulate. Long-term tests must be undertaken.

Given these facts, the suppliers of varnish to flexible packaging producers tend to consider themselves as being in a very secure position. This is not because of the uniqueness of the product itself but because approval processes for new products limit a buyer’s choices. The strategic value of the supplier is therefore rather limited, but the downside potential if the supplier causes trouble is quite high.

With this background in mind, one varnish supplier started a dangerous journey. It increased prices step-by-step—in some negotiation rounds even double digit. But the service quality of the supplier was decreasing and delivery issues started. The customer was obliged to hold significant inventory levels of varnish in order to overcome bottlenecks. Up to this point it had done so, since it was clear that no varnish means no production. When the supplier threatened to stop supply, the customer realized that it was time to deliver an up or out message. Even the supplier’s biggest supporters in production supported this approach.

The supplier was invited to a meeting with the management team and its shortcomings were made transparent. The potential consequences, like switching away from varnish for new products or even a complete shift to another provider for all products, were not taken seriously by the supplier.

This laissez-faire attitude was not a sensible philosophy. After two months with no improvement, the supplier was informed that it was being replaced. Of course, the customer did not only wait but used the time wisely to prepare the phaseout. The transparency that was created made clear that not only the yogurt lids were affected by a potential shift but also some other products ordered from the same supplier that had the varnish in their specifications. In total, approximately 3,000 recipes the customer produced for different clients were affected by the replacement.

A transition plan was created for all products. In addition, suppliers that were identified to be replacements were partly involved. The supplier was a bit surprised and shocked that the replacement scenario came into place and was taken seriously by the customer. During the replacement meeting, as a reaction the management of the supplier showed willingness to commit to improve performance, but as previous promises did not show the desired effect, the customer did not change its decision. In the end, the management of the supplier promised to support the transition process professionally. It kept that promise.

The supplier contributed to and formally signed the detailed transition plan and agreed to regular reviews. The process was only marred by an attempt on the part of the supplier’s sales manager to raise prices. This was refused after escalation on the customer side. After 18 months, the transition was complete. The company saved one-third of its original spending on varnish and got access to an innovative and highly motivated supplier, which did not just copy the former varnish but improved the specifications to achieve better workability and longer duration. This made the engineering department happy, because while it supported the process, it was a bit skeptical as to whether the company was making the right move.

In summary, the relationship between the customer and the varnish supplier was clearly in the Mitigate supplier interaction model. The supplier was not performing in terms of price and delivery performance. After being prewarned several times, the supplier was replaced and a detailed transition plan was executed. Because of how professionally the transition was executed, there was surprisingly little bad blood on either side. In fact, the varnish supplier undertook major internal soul-searching as a result of this experience. It has made a conscious effort to up its game elsewhere. In fact, it is even tendering again to win work with the customer that replaced it.

TrueSRM Comes to Marketing

As part of implementing TrueSRM at Heartland, Procurement initiated reviews with each key part of the business to review the supplier positioning and agree on the actions. Laura attended several of the sessions personally. The marketing meeting was particularly fascinating. Scarlet, in her role as chief marketing officer, attended along with Jane Cavendish from Laura’s team, who was responsible for marketing procurement. A number of members of Scarlet’s team also attended the session; in fact, it ended up as quite a crowd, which was not unusual for marketing meetings.

Laura had taken the precaution of having a premeeting with Scarlet to discuss the ideas that Procurement was about to put on the table. Scarlet was receptive but she wanted her team to be taken on the journey rather than for her to dictate an outcome to them. The big elephant in the room was that despite its commitment to strategic sourcing, Heartland had not run a full creative agency pitch for some years. This was an area that Thomas had chosen not to tackle as CPO; there had been bigger issues to deal with.

But there was an increasing sense that Heartland was not getting what it needed from the agency relationship and that a change might be needed. This had nothing to do with cost but all to do with the level of creative input that the agency was giving. Quite frankly, Heartland’s advertising lacked the freshness of Calbury’s, which had won plaudits for making consumers feel good in very simple ways—like the famous example of a gorilla playing the drums to the strains of the ’60s Matt Monro hit “Walk Away.” Almost unbelievably, this had accounted for a big sales increase. Delta Creative, Heartland’s advertising agency, was nowhere near providing this level of creativity. The whole advertising package was very stale. However, not all of Scarlet’s team shared this view, even though Scarlet was sympathetic with the view that a change was in order.

The first minor hiccup to be conveyed in the marketing meeting was that the marketing people were surprised that no suppliers were shown as belonging to the Critical Cluster in the top right-hand quadrant of Laura’s Three Clusters model, which she presented to the team projected on a screen showing the interaction models and their supplier plots. Jane explained that the categorization was from a corporate perspective rather than a pure functional one. In this light, it had been hard to think of any existing marketing supplier as strongly supporting Heartland’s competitive advantage. It was felt that even Delta Creative really only carried out a workman-like role rather than one that strongly differentiated Heartland. The company was accordingly positioned as Sustain. Even Scarlet’s marketing team accepted this view after some discussion, during which Laura had to intervene a couple of times in support of Jane.

After a brief coffee break, Laura decided to go on the offensive: “Shouldn’t the creative agency be doing more than a workman-like job?” she exclaimed. “I wonder if something needs to be done about it. We have positioned the company as Sustain, but I wonder whether we should really be more aggressive. Its performance does not seem very good at all from what I am hearing. Also, it is not clear that it is attracting the right creative talent, which would mean it could turn things around. Its strategic potential feels limited to me, too.”

Laura boldly walked up to the screen showing the interaction models and their supplier plots. She pointed to the bottom left-hand corner and ventured: “Why don’t we just face reality? Delta Creative is a Mitigate supplier, which means we really need to replace it. That is the logic of what we’re talking about.”

For a few moments, there was silence in the room, as everyone took a sharp intake of breath to contemplate what Laura had said. Then, Dean Everley, Scarlet’s head of marketing, spoke in his thick Tennessee accent: “Laura,” he drawled, “I think you might have a point. Delta Creative is getting a bit long in the tooth. Its creative pipeline is poor and it sees us as a cash cow. Maybe we should replace it and get another agency with newer ideas, a company that is hungry to serve Heartland. I’m not sure we want drumming gorillas, but we sure don’t want the nonsense we are currently producing. What do y’all think?”

The dam had well and truly burst. Dean had voiced what others were thinking but could not bring themselves to articulate. The relationship with Delta had gone on so long that no one relished the idea of replacing them and losing some genuine friendships. There was general agreement though that Delta Creative did need to be replaced. Scarlet had been prepared to force the issue herself if necessary but was happy that the team got there without her pushing them.

The public announcement that would follow saying that Heartland was reconsidering its creative agency relationships was big news in the marketing press, given the size of the account and the longevity of the relationship with Delta Creative. Out of fairness, Delta was given the opportunity to participate in the pitch. But its underperformance counted against the company and they lost the contract. Heartland put in place a transition plan and, to be fair, Delta played its role in the transition professionally. The separation was as amicable as it could be under the circumstances. However, it was no longer a supplier to Heartland.

Delta learned from the experience and later won business with two other smaller and less complex accounts; it vowed not to take them for granted the way it had with Heartland.

Characteristics of Develop Suppliers

Develop suppliers are typically thinner on the ground compared to the rest of the Problematic Suppliers. For a company with 1,000 suppliers, we would not expect to find more than a handful of suppliers in this interaction model. You would not wish to see too many suppliers in this model because that would be indicative of an overall poorly performing supply base.

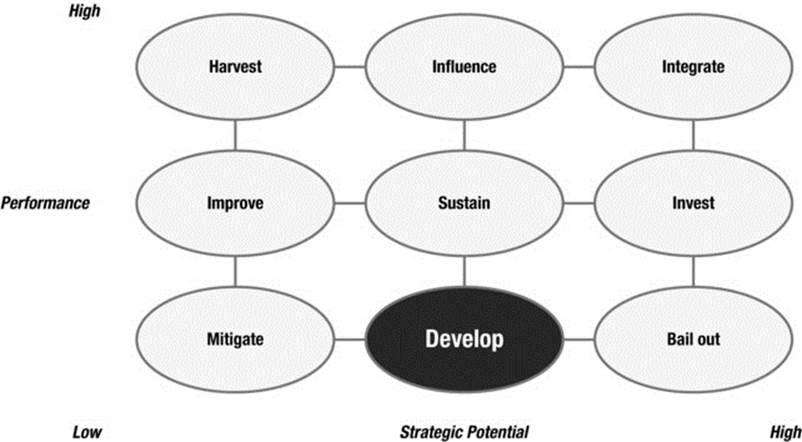

Generally speaking, suppliers in Develop (Figure 6-2) could become interesting and promising because their strategic potential is slightly higher than that of the vast majority of suppliers working with the company. The products and services these suppliers provide could become important for the company’s position in the market. The potential needs to be tapped by identifying opportunities across the value chain of both the supplier and the company. One thing is clear: the supplier is currently not ready for prime time but it has the potential to become a star supplier in the future.

Figure 6-2. Develop suppliers

Suppliers in Develop can also be found in those who have severe operational problems and show performance that is in the back quartile of all suppliers. Yet there is something about them—a spark, an enthusiasm—that separates them from Mitigates. Their poor performance needs to be addressed. It is not a disaster if such a supplier fails but just a lost opportunity.

Recurring performance issues are the reason why there is no competitive advantage and a lack of operational benefits at the moment for the Develop supplier. These issues can be fixed in a way that the company benefits from a supplier. There are numerous examples of Develop suppliers that became key resources in well-managed relationships.

Consider, for example, the many manufacturers that nurture low-cost country suppliers by providing technology or engineering assistance to get them up to speed as component suppliers. Imagine that the supplier fixes its operational problems, which brings great benefit and competitive advantage to these manufacturers—mostly in terms of cost, but also in terms of technology improvements.

What Kind of Behavior to Drive

The desired behavior of the Develop supplier needs to be discussed in the context of future business opportunities. The supplier needs to perceive a unique chance to grow significantly and needs to be willing to follow a given development plan. It is required that the supplier is open to working with the company’s people across its organization.

A triangle of trust, confidence, and commitment needs to be in place. The supplier needs trust in the growth opportunity and in the company itself, and believe that the support will be to its benefit. The project leadership in the Develop interaction model from the supplier’s side has to be confident that the operational improvements are achievable because the supplier has to drive the improvement.

This leads us to the idea of commitment. Speaking about Develop, with some significant benefit for both sides, it is not something that should be managed as just another initiative by a key account manager. Given the major strategic impact, the management needs to be committed to drive this improvement. The supplier needs to allocate core resources for improving engineering, manufacturing, quality, or operational capabilities.

The supplier should be encouraged to work on its performance with quite a bit of involvement by the company. The recommendations of these resources need to be implemented.

How to Work with Develop Suppliers

The key challenge of working with Develop suppliers is to identify the right organizations, those able to accept the challenge of becoming an important supplier. Because these suppliers receive significant support, there needs to be the right balance between investment and return in this relationship.

The conversation with this supplier should start with the presentation of a business case and a plan that reflects the interest of both parties. The supplier should also be made aware of the potential volume allocation for the future. The objective is to motivate the supplier to change its setup and processes. As the supplier needs to allocate core resources, the company itself also needs to dedicate core resources to improving the supplier’s engineering, manufacturing, quality, or broader operational capabilities. These joint teams will align and set standards for future interaction.

![]() Note Make sure that any changes are communicated fairly with the Develop supplier, even if—or better, especially if—changes in the original business plan or volume allocation occur. If market rumors reach the supplier about your company, the relationship will be significantly harmed.

Note Make sure that any changes are communicated fairly with the Develop supplier, even if—or better, especially if—changes in the original business plan or volume allocation occur. If market rumors reach the supplier about your company, the relationship will be significantly harmed.

Governance

Reach out to your in-house, cross-functional teams to identify viable candidates for being a Develop supplier. Your business needs and the strategic potential of the supplier need to be aligned.

After having handpicked the relevant supplier, a supplier meeting should be set up that encompasses not only the traditional supplier’s salespeople and your company’s procurement people but also other functions like engineering, manufacturing, quality and operational capabilities, and most important: the management.

When both parties have the same understanding of the future and the motivation to turn Develop into a beneficial interaction, the collaboration begins and joint teams start working. The Develop effort needs to be executed as a rigorous project with clear reporting and milestone tracking. The supplier’s performance has to be monitored closely and regular biweekly meetings need to be set up.

Finally, once both parties are aiming for the same goal, performance needs to be monitored by cascading objectives down to every employee level affected by the new relationship.

Case Example

Everybody driving a car thinks about the design, the engine, the investment cost and ongoing cost, the color, and potentially about the environmental effects in terms of sustainability. Hardly any customer thinks about the steel that is in the car, even if we observe that a car consists of approximately 50–55 percent steel.

Some might say that steel cannot be the real challenge in supplier-company relationships because there are many steel producers on the market. In our estimation, there are about 130 serious suppliers. All these producers are either producing blast furnaces with iron ore, coking coal, scrap, oxygen, or alloys, or in the case of electric arc furnaces mainly with scrap. Production technology is asset intensive.

Depending on the alloys and the production process, steel types have different functions and can be used for different purposes. It is quite obvious that railway tracks, construction steel, or steel for big ships fulfill other specifications than automotive steel. Automotive steel is one of the most sophisticated types of steel. The requirements from automotive OEMs are high, as the automotive steel needs to cover the balance between elongation and yield strengths. This means, on the one hand, it should be good in terms of formability to be able to fulfill all design aspects. On the other hand, it should have enough stiffness to have a maximum of security for the driver and passengers in the car should it crash. In addition, the flat steel portion of a car requires hot-dip galvanizing, which itself requires some experience and also additional investments.

As a consequence, there are only a very few suppliers in the world that are able to fulfill automotive steel requirements and even fewer steel producers that are able to fulfill them for the premium carmakers.

China is the fastest-growing automotive market. From 2013 to 2020, the number of cars in the country is expected to double. Sales are expected to be around 30 million cars in 2020. The car manufacturers are well aware of this situation and have created new production facilities in Asia and especially in China. This will secure growth while keeping roots in the saturated markets. But the new facilities also create some challenges in terms of supply. The same growth story creating pressure on supply is true for steel. In former times, there was no supplier that was able to produce automotive steel in China.

One of the automotive companies realized this situation of constrained supply quite quickly. This was after having imported the required steel from other countries at a high cost. It then started screening the supplier market in China for steel. About 60 mills were identified that would have had the size to play in this market. A handful of suppliers had already made their first attempts to go into automotive, but without any success. The goal of the automotive OEM was to work with a Develop supplier to have a source in the country that could produce steel at Western European automotive standards. The company already had a relationship with two suppliers for certain steel parts by that time, but the satisfaction level with their overall performance was limited.

Nevertheless, top management meetings were set up with both companies to create an understanding of the future mutual benefits and how the OEM would invest its own resources to develop this supplier. A business case was created and showed that the overall tonnage in the optimistic scenario would have filled about 15 percent of the overall capacity of one of the suppliers for years. Interestingly enough, the first reaction of the companies was not excitement as was expected. China’s economy was growing fast and there were significant investments in the country’s infrastructure, so the companies saw their growth potential there. Besides, prices, due to supply shortages, were quite favorable. So, why add additional complexity in the process by doing hot-dip galvanizing and increased quality control?

The discussion around diversification, long-term contracts, and stable utilization that the automotive industry could bring was, however, successful and one supplier was selected for Develop. In a first step, the key resources on both sides were identified. A team was formed under the leadership of an employee who worked in former times for an EPC, or engineering procurement construction (a company that builds big plants), and afterward for a Western European steel producer, and finally settled with the Chinese supplier. Capable employees were nominated for the project team from the supplier’s side. The OEM dedicated staff from engineering, the key expert from the stamping department of manufacturing, and quality-control people. In addition to its own people, the OEM also mobilized some experts from the current supplier in Europe. These experts, who came with expertise in the different steps in production, such as pig-iron production, steel milling, continuous casting, and hot- and cold-rolling mills, as well as hot-dip galvanizing were integrated. This was possible as there were no strategic plans to enter the Chinese market or vice-versa.

A project time plan was set up and executed diligently. Testing facilities and resources were made available by the OEM. After two challenging years, the first coil was delivered that was used in series production. This was a significant breakthrough for both the supplier and the OEM. Having an exclusivity agreement for a certain period of time brought significant advantage to the OEM and a solid utilization to the supplier. The investment of the OEM paid off!

Implementation Challenges at Heartland

In order to advance the implementation of SRM at Heartland, Thomas had increased the frequency of meeting Laura to weekly one-on-ones. Laura started the meeting by putting a folded page of the Financial Times in front of Thomas. On the page, one paragraph was bracketed.

“I read an article on the plane yesterday. It is about how carmakers deploy supplier development functions and how Japanese carmakers are leading in this sector. I was wondering if this is what we need here at Heartland to bring the Develop supplier interaction model to life.”

Laura knew that deep down, Thomas was still an automotive guy and that he would share his experiences from his time working at Autowerke with passion. She would not be disappointed.

“Interesting that you are showing me this article,” Thomas commented. “I was involved in upgrading Autowerke’s supplier development function early in my tenure there myself. As a matter of fact, I spent two months in Japan learning from the practices of Japanese carmakers.”

“What is so special about the way they do it?” Laura asked.

“Carmakers in America and in Europe have always had some kind of supplier development function, but it has largely been limited to certifying new suppliers, auditing quality, and identifying savings potential in production. Japanese carmakers have followed a higher-touch approach. They would have more and better-qualified people on the ground and actually help the suppliers with implementation teams and resident engineers. While Europeans and Americans saw supplier development mostly as programs to enforce price reductions, the Japanese saw it as an investment in the future in order to get more innovation. And this clearly paid off. There are many surveys that demonstrate the extent to which suppliers prefer Japanese carmakers over their European and American competitors. They clearly achieved a competitive advantage through improved quality and shorter time to market with better product technology.”

Laura was taking notes while Thomas was speaking, “And what did you do in Japan?” she asked.

“Well, I believe that Autowerke was the first Western carmaker to fully understand the advantage the Japanese OEMs were getting out of supplier development. We entered a partnership program with the biggest Japanese carmaker in which we essentially traded our experience in diesel engine technology for their experience in supplier development. I was then part of a fairly large group of Autowerke people who spent time working in their supplier development function. If I remember correctly, we had four different teams there. One was focusing on supplier assessment, the second on interventions—meaning when something goes wrong at a supplier and you have to fix it—the third team was focusing on proactive supplier development, and the fourth one on monitoring and control. I was part of the third team, for which my subgroup focused on the Japanese way of ensuring global-production readiness at suppliers. We called it cannon launch.”

“And how did you incorporate this at Autowerke?”

“Oh, this was a fairly long process—it took at least two years, I think. We started with reactive measures in order to better respond to issues our suppliers were having. Once suppliers had gained confidence in our ability to help them out, we gradually moved toward more proactive measures to help them improve their performance. Suppliers actually had to pay for our services. Initially, 75 percent of the cost was funded by Autowerke, but over time we switched to 100 percent supplier funding. This was actually very successful and our function grew to well over 200 supplier development people.”

Laura appeared to be discouraged by this. “Wow, there is so much to do in parallel. How can we get anywhere close to where Autowerke is on this? We can’t seriously start sending people to Japan . . . .”

“You don’t need to, Laura. We can hire a couple of folks from Autowerke to be the nucleus of our own supplier development function. I know most of the key people there and I am sure that I can have a good team on board within a month or so.”

Characteristics of Bail Out Suppliers

In addition to Integrate, Bail Out has the lowest number of suppliers in the SRM framework—but these suppliers are really handpicked. For a company with 1,000 suppliers, we would expect to find less than a handful of suppliers in this interaction model.

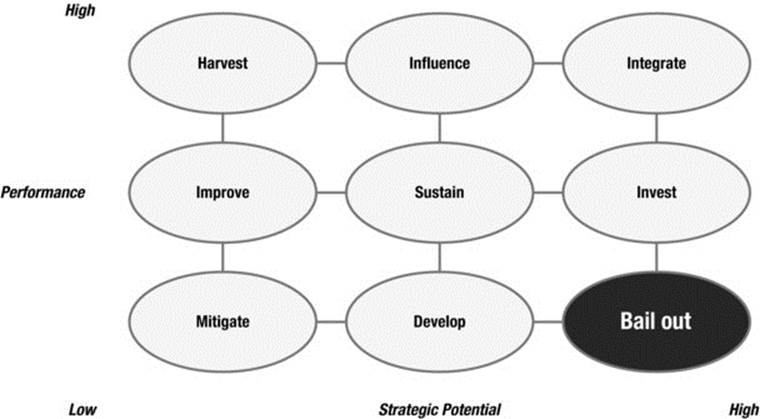

Generally speaking, suppliers in Bail Out (Figure 6-3) are highly interesting and promising. Their strategic potential is outstanding and much higher than that of the vast majority of suppliers working with the company. The products and services these suppliers provide are innovative and can be a differentiation factor for the company’s position in the market.

Figure 6-3. Bail Out suppliers

Nevertheless, their performance is poor. This could be based on an egregious error or a chronic problem that suddenly requires triage. Such situations can significantly jeopardize business by threatening supply or even the launch of a new product.

The immediate goal is to stabilize the supplier’s performance. The long-term goal is to learn from the problem to avoid future bailouts with this supplier. It may seem counterintuitive, but this is a relationship that needs to be maintained, particularly with important suppliers. The Bail Out relationship should be brief, rare, and regarded as temporary step toward improving the overall supplier relationship.

Usually, the help is provided by you without considering what you will receive in return. Supply is threatened and you step in to correct matters. Ensuring ongoing supply is generally seen as a sufficient short-term payoff. There is not time to discuss how the help will be funded other than a quick consideration of available contractual damages.

However, “resorting to contract” immediately, when there is any form of issue with performance, does not fix the problem and is not usually an effective remedy. It also kills the relationship, and, remember that the supplier has outstanding strategic potential. Killing the relationship would not be a good long-term outcome. If there is time, instead think about more creative long-term payoffs the supplier can make in return for the help, such as exclusivity on certain products or even a part ownership share in the company. In the heat of the moment, it is difficult to think of the long-term relationship. But demonstrating your longer-term commitment will have a strong payoff.

What Kind of Behavior to Drive

The desired behavior of the Bail Out supplier is to acknowledge the severity of the situation and allow your company to intervene. To do this, the supplier needs to see the benefit it will get if it complies with the actions of the Bail Out plan.

The major investments the company makes in Bail Out suppliers will make it obvious that you have a special interest in stabilizing and strengthening the relationship. This can be communicated in a way that the supplier sees that correcting the situation will be a joint effort and also a joint benefit in the end.

This also means that the supplier should not only comply with the instructions given by the company and its potential external experts but also come up with meaningful solutions to fix shortcomings.

![]() Note To sum up, a high ambition and motivation level of the supplier and the company, trust, and beneficial collaboration are the ingredients of success in the Bail Out interaction model.

Note To sum up, a high ambition and motivation level of the supplier and the company, trust, and beneficial collaboration are the ingredients of success in the Bail Out interaction model.

How to Work with Bail Out Suppliers

Bailouts are expensive for everyone and time is king. This means that it is key to recognize the bailout situation immediately in order to reduce damage and to help save the relationship. It is necessary to have an open relationship with the supplier.

As there are very specific challenges that have to be resolved in bailouts, it is obvious that not everything can be fixed by the in-house experts of the company. Leading companies therefore have arrangements in place with external experts who support them in fixing problems based on their unique experience. Furthermore, using external experts will avoid bottlenecks in the company.

The company’s office is not the best location for managing bailouts. Usually, the supplier’s premises are the right place. This allows access to all stakeholders, access to production, and access to real-time updates. It is thus better to have boots on the ground sooner than later.

Companies often lose sight of the fact that a Bail Out supplier has high strategic potential. As a result of this, they make a major error. Once the original problem has been fixed, they sometimes feel let down by the supplier. As a result, they quickly jump to replace the supplier with a different one. This is not the right outcome. If the supplier really has high strategic potential, then the right answer is to carry on nurturing it to enable it to progress and achieve the full potential you can get from the relationship. The company’s ambition for a Bail Out supplier ought to be for it to achieve its potential and ultimately be in the Critical Cluster, not be replaced.

Governance

The governance needs to recognize three key requirements: First, suppliers usually drop into Bail Out as a result of a failure. Predicting and preventing failures in advance is a crucial governance need. Second, once a supplier drops into Bail Out, the appropriate task force needs to be in place with the right governance to ensure that the issues are addressed. Third, once the issues that led to the bailout have been stabilized, then the right governance needs to be in place to prevent recurrence.

In terms of the first point, in order to recognize Bail Out situations quickly and early, there needs to be an early warning mechanism in place. The difficulty for problems with new products and new technology is that early warning mechanisms are hard to determine. One can, for example, study the trends of performance data and carry out supplier audits. Governance needs to be in place to ensure that the results of such work are reviewed across the supply base. If issues are flagged, then the appropriate guidance needs to be given to the supplier before the bailout is triggered. However, no such technique is foolproof and some bailouts will always elude the early warning system.

The second issue involves ensuring that the right governance is in place to ensure that cross-functional and external support can be deployed once a bailout is indicated. This will need to be done urgently—an important, innovative supplier with high strategic value needs help. A task force consisting of representatives of the supplier, the company, and external experts needs to be created. Both the supplier and the company need to dedicate resources. This task force drives the performance improvement in a project type of setting. A kind of war room setup enables the joint team to execute the project and to make the improvements transparent. A joint steering committee will need to be in place to govern the work of the task force and provide an escalation point. It is also crucial to avoid encumbering the task force with commercial or contractual topics. Allow the task force to fix things. Deal with any commercial concerns separately and at a steering committee level.

In the third requirement, once the situation is stabilized, the task force can be unwound and the governance revert to a more business-as-usual approach, with the supplier being able to manage its own affairs without detailed day-to-day intervention on your part. There is a balance to strike here between the risks of unwinding the task force too quickly vs. the more desirable choice to revert to the normal state of affairs. Agree on a joint plan for reverting to normal. Review progress. Take a gradual approach and be prepared to step in again as you slowly wind down the task force. As you do this, make sure that you put in place the right governance measures that will help to prevent recurrence of the issues that gave rise to the bailout in the first place. Assess the risks of recurrence. Be prepared to put in place more detailed ongoing oversight than may be your norm. But, be careful too. The supplier needs to stand on its own two feet. Do not over compensate for past failings. Base your approach on a true view of the real, not perceived, risks. Managed well, the supplier will be on track to continue as a valued member of your supply base.

Case Example

Most people relate battle tanks to war and many things that are not really nice. We should not overlook the fact that battle tanks are also used for peacekeeping and for the self-defense of countries. We are going to come back to this point.

Despite all the bad feelings that come along with speaking about tanks, we have to admit that they are fascinating from an engineering point of view. Depending on the type, these vehicles have a double-digit tonnage, are able to drive over 100 kilometers per hour, can swim, can crawl after swimming in muddy shores, and can climb mountains with inclines of up to 70 degrees. These are indeed quite-impressive specifications.

Nevertheless, the core pieces of a battle tank are engine, steel, electronics, and protection systems. While the first three categories are supplied by big players like Cummins, MTU, SSAB, and others, the protection systems could be supplied by quite an innovative player.

A very successful company in the land-defense sector got a new contract from the Ministry of Defense from a specific country. While the company had a proven protection system from a well-established supplier, R & D was working to gain a competitive advantage by enabling a new protection system for the tank. R & D was working very intensively, in particular with one supplier that had a completely new technology. Tests were performed in top-secret locations, and waste was eliminated so that nobody could have any hints of this new technology. Neither sales, nor engineering, nor production had any doubts that this new technology was leading the market. No other supplier than this one could bring the same reduced weight to the protection system by increasing the degree of protection. Impressions on the overall setup of the supplier were also good. The client, a national Ministry of Defense, was also confident in this new technology and the client’s engineers were excited about it. This new technology was also one of the winning factors for the overall contract, a clear strategic advantage for the company.

After the preparation phase, production started and suppliers made their first deliveries. Beside the normal challenges in a project-based business in this sector, the new and highly praised protection system brought severe problems. The quality was not consistent, the deliveries were delayed, and the operational performance overall was a disaster.

The company had some experience with low-performing suppliers and reacted in the right way. A task force was established and sent immediately to the supplier. It was not an easy step given the fact that the big contract had to be managed, but with the necessity and also the strategic advantage, the management freed up resources. Already, after the first poor-quality deliveries, they had their feet on the ground and worked together with the supplier, which fully realized that these operational issues could wipe it out of the market.

The task force supported the supplier to bring the new innovative technology to a consistent quality level and enabled the supplier to manage its operations professionally. This company’s relationship with the supplier got very tense over the period of the bailout. Nowadays, the company is highly profitable, and, after a period of exclusivity, opened the market to others, too. A nice unexpected outcome: this supplier always offers its innovations first to the company that helped it in fixing its problem—a continuous strategic advantage.

Heartland: Calbury Races Ahead

Thomas was in a rueful mood. Laura sat down. He opened up his iPad and handed it to her and asked her to look at the screen. “Calbury sure is doing well with that ‘Taste Fresh Longer’ packaging that it sources from Marshfield. See this announcement here of the extra sales that the company is driving from it? Well, the company’s not just making extra sales on the product but both companies are also making really nice margins.”

“I saw that earlier as well,” said Laura. “The joint venture that Marshfield and Calbury set up has a patent on it, as you know. They are really not interested in making it available to anyone else.”

“I heard talk that they might be making it available soon,” Thomas offered.

“So far, it is just rumors,” Laura speculated. “I think what they will do is make a less-sophisticated version of the packaging available more widely. They are worried about competition concerns, and Marshfield does have an interest in driving more volume than they get purely from Calbury. But the most sophisticated formulation of the packaging will remain exclusive to Calbury we hear—at least for the foreseeable future.”

“Right now, our response is to work with another company to develop an alternative that does not infringe the patent,” suggested Thomas. “That will take time and be expensive. Or we just hope that Marshfield’s competitors will do something anyway. In the meantime, our retail customers are keener to push Calbury brands in what is one of our prime categories. Not a great place to be in.”

“You know,” said Laura, “things could have been very different.”

“How?” asked Thomas. “Marshfield has been quite a peripheral supplier to us for quite a while. We have only kept buying the product that we needed for logistical reasons, really. But the company has been one of Calbury’s major suppliers for a long time. Calbury did a lot to build the relationship and ecosystem that we are now seeing in place. Our failure has not been not doing the same thing with someone else.”

“You know it was not always like that though, Thomas. A few years before you joined from Autowerke as CPO, the company was actually seen as a key supplier. I remember that it supplied our Italian plant. It was really significant.”

“I did not know that. What happened?”

“We had the great ‘ripping of film’ drama about five years ago.”

“I did hear someone refer to that,” said Thomas. “What has that got to do with it?”

“Well, Marshfield was our biggest film supplier. You know how production people are with film. A lot of the specifications are custom-made and take practice. Accordingly, they are hard to codify. The production people hate changes, even if they might be beneficial.”

“Right, tell me about it,” said Thomas.

“OK, so Marshfield came to us with a great idea to make the film stronger and even more lustrous to the touch while still being thin. It would make the product look better. It was an interesting innovation, but our production people were reluctant to do it. It would be slightly cheaper, but that was not a real reason to do it and Procurement had no real power at that time anyway. However, the fact that it made the product look better meant that it got support from Marketing. So, it was agreed to do a trial on the new film in one of our plants—the one in Ulm.”

“That was a brave thing to do, then,” said Thomas.

“At the time, it came to be seen as something quite beyond ‘brave.’ It was set up as a pilot, but Marshfield had all sorts of problems with the new film. First, it started to break in our machines, even though it was supposed to be stronger. That was, in reality, partly our fault due to how we were running the machines. Then, Marshfield had problems making enough of it in the right quality and consistency. We did not have a supplier development team back then, but we did put some production engineers in there to help sort out the problems. It was a bit like closing the door after the horse had bolted.”

“I see,” said Thomas. “So, it was a bit of a panic?”

“Oh yes. Many people bore the scars. We got it fixed in the end and no actual product was affected by the problems. Also, the production schedule was not really hit because we had inventory anyway. We always had lots of inventory of film in those days, whether we needed it or not.”

“What lessons were learned?” asked Thomas.

Laura laughed. “Not the lessons we should have learned. What we should have learned is that for a product change like that to be successful and for real innovation to take place, you need to carry out joint planning up-front and collaborate. We did not do that. We just went into crisis mode at the first sign of trouble.”

“What else happened?”

“That is the real tragedy. We blamed the supplier for all the problems. In reality, the fault was on both sides. And, the company was genuinely trying to give us first access to an interesting innovation! For all of its pains, it ended being tagged as an unreliable supplier. We started to move business away from the company. Everyone started to see awarding business to Marshfield as career limiting. So, it became less important. It works both ways, of course. We became less important to the company and it built their relationship with Calbury. Nobody stopped to think that perhaps Marshfield had something genuinely different to offer us. They just focused on the ripping-of-film drama.”

“And the rest is history,” said Thomas. “Calbury reaps the benefits of our shortsightedness.”

“It gets more tragic though, would you believe?” said Laura.

“How can it get more tragic than that?” inquired Thomas. He leaned forward to concentrate. This was really was turning into quite a revelatory discussion.

“Well,” said Laura, “there are rumors in the marketplace. People are saying that the know-how that Marshfield gleaned to create the Taste Fresh Longer line came as a direct result of the ripping-of-film debacle.”

“What? Seriously?!” commented Thomas, surprised.

“Yes. They learned a lot about the chemical properties of how to make different types of film from the incident. Also, our troubleshooting with them at an operational level was highly successful. They learned the additional lesson that collaboration with key customers on product innovation can be beneficial. According to our own rumor mill, they did try to do that with us. But, of course, we were not listening and they had written us off. They turned instead to working with Calbury. Although it took a few years, this led directly to the innovation that is now causing us so much irritation.”

Thomas took his iPad back from Laura. “We really need to avoid similar debacles like this in the future. Let’s learn the lessons.”

Problematics: Handle with Care

In this chapter, we have described the three interaction models that make up the Problematics, or problem children. As we have seen, these suppliers should constitute far fewer than 10 percent of your total supply base. This is just as well because in all cases performance is poor and serious fixes are needed. Where strategic potential is low, you should not incur effort to make the fix but replace the supplier after giving it sufficient opportunity to improve. In other cases, where strategic potential is higher, you should incur effort to nurture the supplier toward greater things.

We will turn our attention in Chapter 7 to address the suppliers that are already capable of these greater things. These are the suppliers in the Critical Cluster—the very small number of suppliers from which you can access true innovation and the ones to which you really want to devote the majority of your attention.