Institutionalization of UX: A Step-by-Step Guide to a User Experience Practice, Second Edition (2014)

Part IV. Long-Term Operations

Chapter 16. Design for Worldwide Applications

Apala Lahiri is the CEO of the Institute for Customer Experience (ICE) and an expert in cross-cultural design. With ICE, a not-for-profit initiative by HFI, Apala has been working with her team to investigate practical approaches for institutionalized user experience design practices to create sites and applications that will be used in countries around the world. It is a problem that many multinational organizations face, yet one of such complexity and scale that few have even attempted a solution.

Do International Markets Really Matter?

Is there a compelling reason for organizations that build facilities for domestic use to be concerned about usage in other countries—or around the world? If I had been asked this question 10 years ago, I would not have been able to give a definitive answer. In today’s globalized market, however, the answer is a resounding yes.

The shift in focus to the new consuming class in emerging countries accompanies a transformation as significant as that brought about by the Industrial Revolution. According to McKinsey & Company, annual consumption in emerging markets is expected to reach $30 trillion by 2025—“the biggest growth opportunity in the history of capitalism.”

For organizations to survive and grow, they have no option except to make their products and services attractive and persuasive to users from the emerging markets. Emerging markets that might once have been concentrated in East Asia are now spread around the world. Concern about global usage is now an imperative.

McKinsey Quarterly’s 2010 article, “Winning the $30 Trillion Decathlon: Going for Gold in Emerging Markets,” observed that

CEOs at most large, multinational firms are well aware that multinational markets hold the key to success. Yet those same executives tell us they are vexed by the complexity of seizing this opportunity.1

1. https://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Winning_the_30_trillion_decathlon_Going_for_gold_in_emerging_markets_3002.

How Does Bad Cross-Cultural Design Happen to Good Organizations?

With English increasingly becoming the language of the Internet and China’s heavy investment in having Chinese students and business people learn English, it might seem as if the efficient solution were for everyone to use the same site and applications. Alternatively, it might seem logical to translate the English-language sites directly, changing units such as currency denominations where necessary.

The essence of localization extends far beyond language and formats, however. Making local language content and formats available is a very good start, but much more needs to be done.

Marketing and consumer psychologists have shown that “culturally congruent” Web content leads to decreased cognitive effort for categorizing, processing, and interpreting information on the site, creating in turn a more positive attitude toward the website.2 Culturally congruent content/communication, built upon a foundation of cultural schemas shared by users, requires less cognitive processing and generates a feeling of “flow” and satisfaction in the user experience.

2. Luna, D., L. A. Peracchio, and M. D. de Juan. 2002. “Cross-Cultural and Cognitive Aspects of Web Site Navigation.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(4), 397–410.

In The Culturally Customized Web Site, Arun Pereira and Nitish Singh describe cultural schemas as “simple elements or conceptual structures which serve as prototypes for underlying real world experiences. . . The cultural schemas we develop are a result of adaptation to the environment we live in and the way we have been taught to see things in our culture.”3 Since cultural schemas consist of much more than language and formats, it is unlikely that a single solution would resonate with everyone in the world even if they were able to read it in their own language and interact with familiar currency and date formats.

3. See Casson 1983; D’Andrade 1992; Quinn and Holland 1987; and Singh 2004 for extended discussion of schemas and cultural models.

Cultural schemas are likely to vary widely among users from, for example, a high-power-distance, collective, long-term-oriented culture that values restraint over indulgence and users from a very low-power-distance, highly individualistic, low-uncertainty-avoidance culture that values indulgence. How users from these two very different cultures interact with a banking site—what they expect to find on the site and their expectations of the bank itself—will differ significantly. Understanding this difference in underlying cultural schemas informs the design of local sites that users will adopt and use.

Internationalization, Localization, and the Challenges of Current Practice

Internationalization (I18n) and localization (L10n) have been cornerstones of cross-cultural UX concepts for over a decade, particularly in the software development world. Looking back at the experience HFI has had with large corporations delivering products and services around the world, it is clear that most corporations have adopted some aspects of internationalization practices. Most of them make it possible for the base product/website design to accommodate local language scripts, images, formats for currency and dates, and other factors. From the perspective of more than a decade of cross-cultural UX advocacy, however, there has been much progress beyond that—not in terms of organization structure or process, and certainly not in a consistent manner.

Microsoft, for example, strongly advocates product-centered groups (often based in Redmond, Washington) rather than global and local teams:

Putting together an efficient product team is a challenge that can make a significant difference to your bottom line—“throwing headcount” at your international editions is not an efficient use of resources. If your entire team, including developers, designers, testers, translators, marketers, and managers, is committed to all language editions of your product, and if management holds them responsible for all language editions, you won’t have to hire a lot of extra people.4

4. http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/cc194771.aspx.

On the other hand, Infosys, one of India’s largest systems integrators, emphasizes the major role of software productivity tools in its internationalization process:

Staffing for i18n/L10n projects is normally done by bringing in people who have prior experience of internationalization along with a team which is well versed in the technology underneath (Java, C++, etc.). In these cases, there is generally the overhead of training the team on i18n and L10n concepts. Unless the whole team fully understands the internationalization process, they will not be very productive. In the real world, it is almost impossible to get a perfect team which has good internationalization experience in addition to the required technical skills. Also, with tight deadlines looming over us, most of the time it is not possible to invest a lot of time in training the team on i18n/L10n concepts. So the best way to execute the project is to improve the productivity of the team by using software productivity tools and in turn enhance the productivity of the internationalization process itself.5

5. http://www.infosys.com.

In addition, organizations such as Facebook, YouTube, and Google are considered models for internationalization owing to the speed of their crowdsourced language translation and local content.

Organizations in domains other than technology, such as retail, logistics, banking, health care, and appliances must grapple with the same issues. They must balance the time and cost involved in providing the most culturally appropriate design/products/services to local customers across the world.

Between the Idea and the Reality Falls the Shadow

While the intent is to provide localized solutions, in a majority of cases the result is quite different. The outcome usually ends up being a solution or a set of solutions that is created in the country of origin and then internationalized in terms of its language and unit measurements. The blame can be laid squarely on the absence of a practical, cost-effective of a process that goes from understanding the local ecosystem through design and validations of the application.

The amount of time and cost involved is really the “shadow” that falls between the intent of providing localized solutions and the reality of researching and understanding many local ecosystems throughout the world.

The Criteria for Success

The test for globalized design is, of course, how much adoption and usage of localized websites, products, and services occur. Nothing succeeds like successful conversion.

The challenge lies in balancing the optimal “fit” of a solution to the local ecosystem with the cost and time required to deliver it. Our group, ICE, has been giving this topic a great deal of thought as it explores different possibilities for global corporations to deliver local solutions in a realistic, cost-effective time frame.

A New Global Delivery Model for Local User Experience

To create a set of localized solutions that delivers the necessary level of quality for adoption without serious damage to the bottom line, ICE has a draft model in place based on two key concepts.

Foundational Ecosystem Model

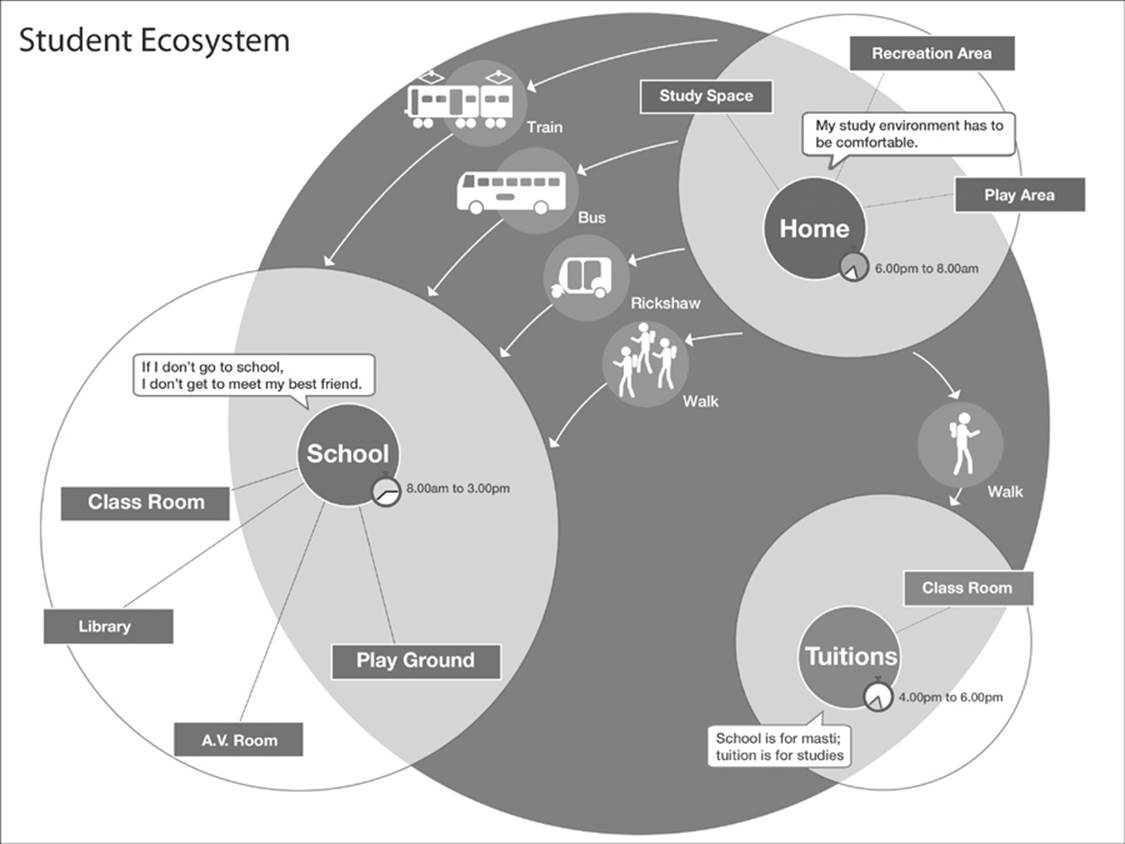

We believe that the creation of a foundational ecosystem model of its customers is a key first step that a global organization needs to take in its journey to provide local UX solutions. This model will in many ways approximate the current internalization (I18n) template for software, but features placeholders for deeper cultural factors in addition to formats, colors, language, and images (Figure 16-1). This ecosystem model will typically be based on previous primary and secondary research, marketing data, and Big Data insights—and, in the future, on data gathered increasingly by the Internet of Things and crowdsourcing.

Figure 16-1: Example of an ecosystem model

This foundational model can then be used for creating first an internationalized, and then a localized, set of ecosystem models—the “cultural” equivalent of the L10n process. The localized ecosystem models can be iteratively edited, enriched, and tested by local, in-country professionals.

These models can grow over time, in both the range of data they are built on and the depth of their understanding. They can also grow in the number of regions and countries that are separately included.

“Cultural Factors” Training

Where would an organization embarking on its multicountry localization journey ideally find and hire large numbers of UX professionals in every country? Aside from the logistical challenges that this approach presents, the primary problem has been the dearth of UX professionals across the world.

We suggest a different approach to solve this problem, one that leverages remote training on “cultural factors”—a blend of human factors, cultural anthropology, and social psychology—as well as on how to conduct usability testing, to those who want to be certified in cultural factors and/or usability testing. Those taking the certification courses do not necessarily have to be UX professionals, but rather could be local staff of the organization or even local free-lancers.

Being able to access a large pool of certified professionals in cultural factors and usability testing across the world would enable multinational corporations to take a quantum leap in developing localized solutions in an accurate, efficient, and cost-effective manner.

Critical Tools

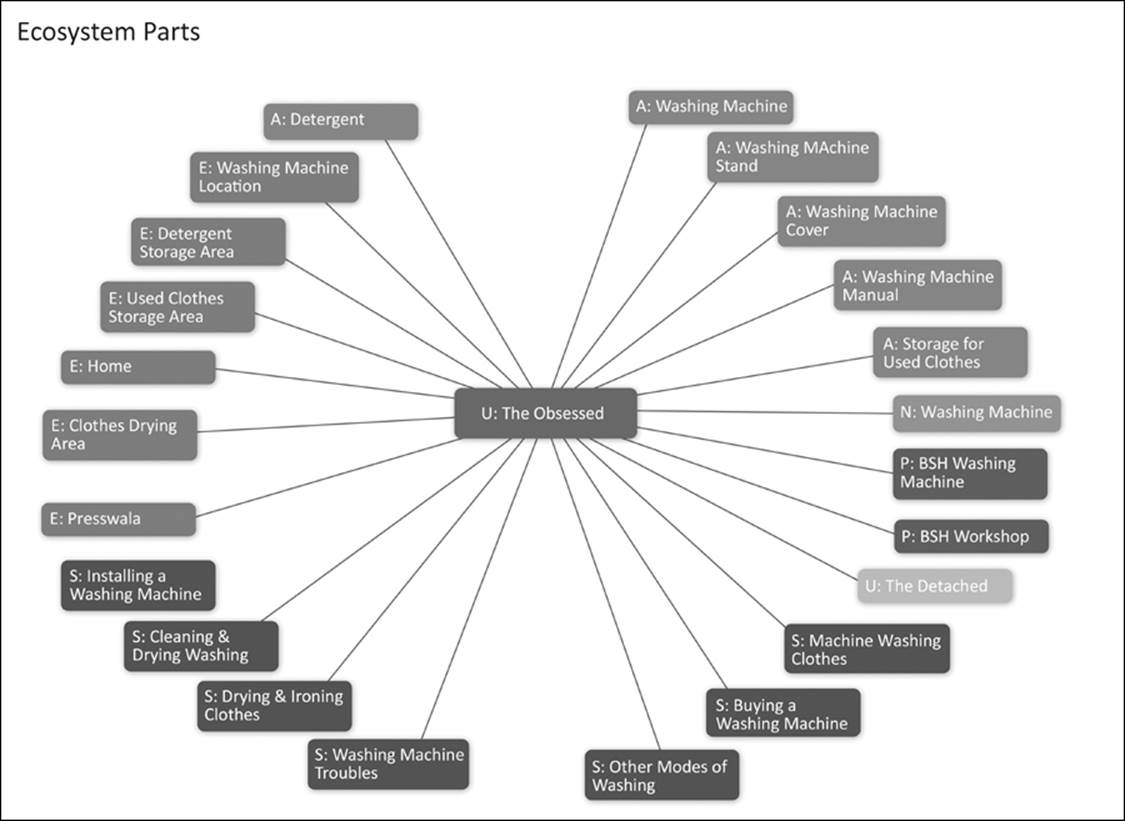

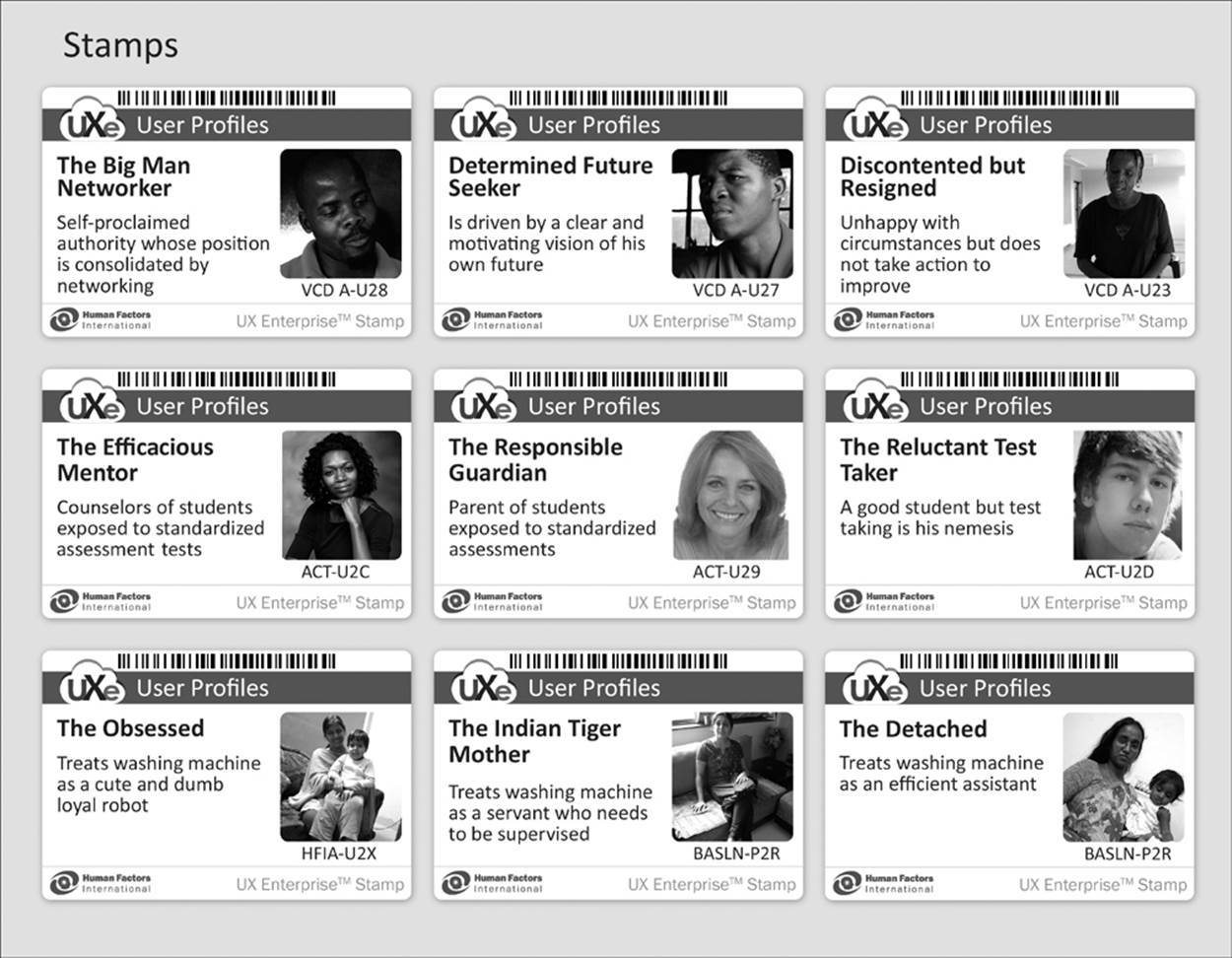

Even a good process will be useless if appropriate tools are not available to support the process. To build a foundational ecosystem model to support delivery of localized solutions, one that can be enriched over time in a cost-effective manner, it is essential to have a tool capable of breaking down the user data into components or objects (e.g., personas, scenarios, needs and opportunities, core values, artifacts) (Figure 16-2). This object paradigm will allow reuse of user data—adding, copying, and combining objects—rather than having to start from scratch as new user insights become available.

Figure 16-2: Parts of the user’s ecosystem: scenarios, artifacts, environment, needs, and opportunities

In addition, the tool should allow objects to be linked in a myriad of ways. With the progress of time, as additions are made to the foundational ecosystem model, new objects can be linked to older ones, and new insights/hypotheses can be inferred.

Finally, the tool should allow for seamless collaboration among everyone populating and adding to the foundational ecosystem model across the world.

This tool will serve as the corporate memory of an organization’s global user segments (Figure 16-3).

Figure 16-3: Corporate memory of all user segments

Local Understanding, Global Success

For most organizations, this kind of object-oriented localization will represent a profound shift in approaching global markets. Can it produce designs that will compete with local companies, or succeed in diverse environments around the world?

I have always said, “Think globally; lose locally.” There are very compelling reasons why paying attention to local needs can not only be very competitive, but also serve as a vital differentiator.

A look at India’s smartphone usage landscape says it all. Goliaths such as Apple and Samsung are being overtaken by local Indian smartphone manufacturing Davids; local OEMs like Karbonn and MicroMax are on a roll.

A combination of low prices and “smart” features is fueling the local companies’ rapid growth. Businessweek6 notes that Karbonn, MicroMax, and other Indian hardware firms offer smart phones that are cheaper than the least expensive iPhones or even the Android models offered by U.S., Korean, and Taiwanese manufacturers. Considering that approximately 800 million people in India live on less than $2.00 per day, many of whom are hungry for new technology, this seems like a winning formula.

6. Mehrotra, Kartikay. April 11, 2013. “iPhone Outpaced in Surging India by Less Costly Rivals.” Businessweek.

It is not just Apple and Samsung that have been affected by these local Davids. In the early 2000s, Nokia’s early-mover advantage had allowed this firm to capture India’s cellphone market. As Nokia stopped looking deeply at local needs, however, it ceded some of its dominance to new competitors, unheard-of local entrants in the Indian market.

What had seemed impossible had suddenly happened—a powerful multinational, considered a pioneer in the space, ousted by an unknown newcomer. That newcomer was MicroMax. Started by four friends in 2008, MicroMax used a “deep understanding of . . . consumer needs and the ability to swing their supply chain”7 to become the largest mobile phone manufacturer in India by 2012.

7. http://micromaxcentral.com/micromax-company-profile/.

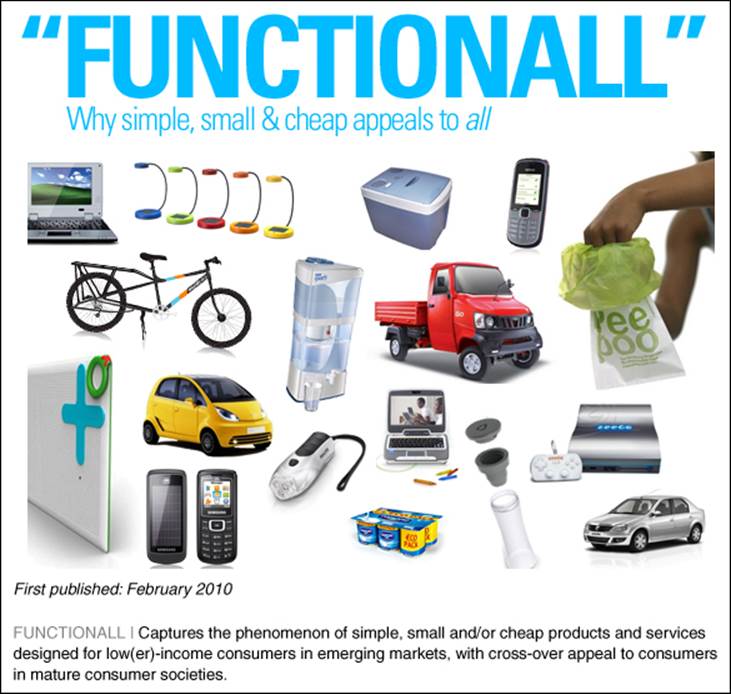

The contextual innovation that comes from understanding local users can lead to success far beyond the local market, reversing the traditional flow of products and services from mature markets to emerging ones (Figure 16-4). Increasingly, designs created for emerging markets set a trend in mature markets (Figure 16-5).

Figure 16-4: Reversing the flow of products and services—from emerging markets to mature ones8

8. Source: Trendwatching.

Figure 16-5: Emerging markets are the source, increasingly, of innovation9

9. Source: Trendwatching.

The business case for investing in localization just got a whole lot stronger. When an organization creates localized products and services, the entire world becomes a potential market.

Are There Populations We Cannot Reach?

Businesses and designers, particularly those outside emerging markets, can be hesitant about designing for users of very limited means, particularly those in cultures that differ radically from their own. Yet poorer population segments constitute a significant proportion of the emerging markets. This approach to localization will actually make innovation for bottom-of-the-pyramid (BOP) segments around the world more likely, as well as more successful.

Ever since C. K. Prahalad’s paradigm-shifting book The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid was published, organizations have shown a considerable interest in servicing the BOP segment and “fighting poverty with profitability.” Some major success stories have emerged as well. Consider the shampoo sachet (Figure 16-6; the forerunner of seemingly everything in sachets!), missed-call-based service models, and the distribution network (shakti ammas) created by Unilever in India and by MPesa in Kenya.

Figure 16-6: A shop in Pondicherry, India, sells sachets of various products

What made these ventures successful? The creators of these innovative bestsellers had their ears to the ground and made sure they understood the local ecosystem of the BOP population very well (Figure 16-7). Rather than simply “poorify” existing products and services, they started with a clean sheet of paper—and no assumptions. Intensive research yielded critical “cultural factors” such as the resonance of the “pay as you use” model—the preferred pattern of infrequent but regular consumption of a small quantity. And so came the shampoo sachet, one of the most successful innovations in recent times.

Figure 16-7: Apala Lahiri gathering ecosystem data in Africa

In short, a robust local ecosystem model helps an organization serve all its user segments, rich or poor, in an optimal manner.

Can We Look Forward to a Unified Globe?

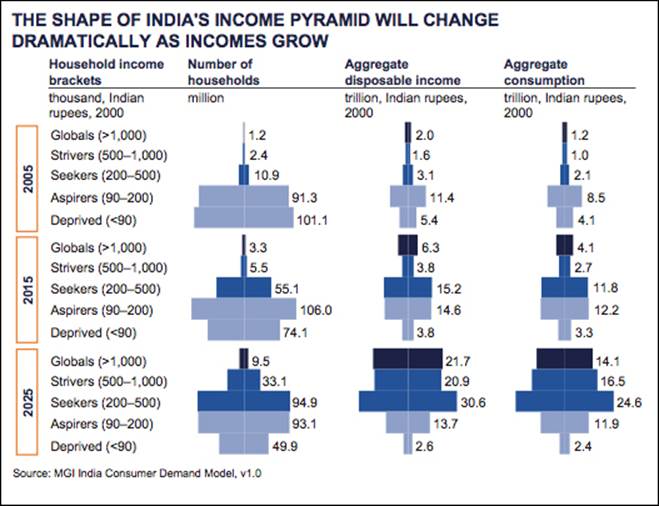

There are those who say that the logical end of the information age is homogenization, a time in which there is enough commonality among people of the world that localization is unnecessary. I don’t share that view—certainly not with the entire population of the world in mind. Of course, the miniscule 2–3% of the population that sits at the very top of the income pyramid in every country has always been rather homogenous across the world (Figure 16-8). With access to the abundance of global resources and exposure over several generations, this segment tends to speak of their motivations and needs in a common language.

Figure 16-8: Incomes and the growth period10

10. Source: McKinsey Global Institute, “The Bird of Gold: The Rise of India’s Consumer Market,” May 2007.

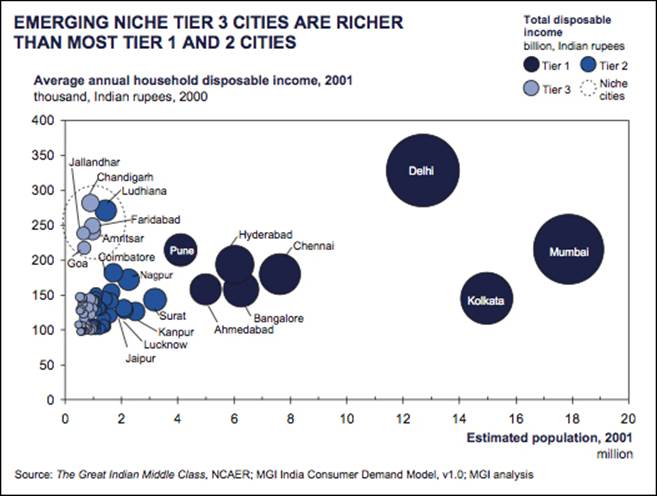

The other 98% of the population—especially in the emerging countries—have not had shared in those resources or had the same access to information and global markets until very recently (Figure 16-9). This rising middle class tends to stick closer to its roots—it is open to using Western-style products and services but with a local flavor. For this segment, unlike earlier generations of consumers, foreign (read Western) products/services do not necessarily have an advantage over local ones. Given that this segment is likely to continue to grow throughout emerging economies, the demand for that “local flavor” will only increase.

Figure 16-9: The surprising wealth of emerging economies11

11. Source: McKinsey Global Institute, “The Bird of Gold: The Rise of India’s Consumer Market,” May 2007.

According to leading market research consultant Rama Bijapurkar:

It is interesting to note that between 1995–96 and 2005–06 the shape of income distribution in urban India changed from the traditional poor country shape of a triangle or pyramid (indicating far more people at the bottom than in the middle and even fewer at the top) to a diamond, with less people at the top and the bottom but many more in the middle.

Projections are that the shape will change to that of a cylinder standing on a narrow base, with equal numbers in the top four income groups and very few at the lowest income group.12

12. Bijapurkar, Rama. 2008. We Are Like That Only. India: Penguin Books.

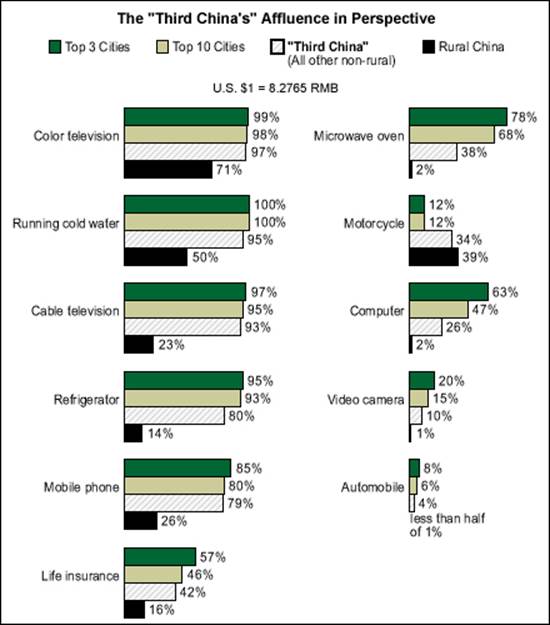

Emergence of the “Third China”

The same trend is evident in China. Hitherto peripheral Chinese population segments are becoming significant consumers. Their emergence constitutes a significant new market segment in a country historically represented by a relatively elite sliver consuming goods like computers, washing machines, and cars, with the vast majority of the population lacking access to those goods. Now there are about 45 cities in China with a population of at least 1 million, and they are growing fast in terms of buying power (Figure 16-10). Yet the requirements of this “Third China” are also very much mediated by local preferences.

Figure 16-10: Understanding affluence in the “Third China”13

13. Source: Gallup, “Still ‘Two Chinas’—But a Third Is Being Born,” February 8, 2005.

With the rise of new consuming classes in emerging countries, it cannot be assumed that those groups reaching certain income levels will have needs and preferences equivalent to those who have enjoyed the benefits of being at that income level for a much longer period.

It is important to understand that simply looking at income levels may not always provide a real and clear picture of the consumer and his/her motivations and buying behavior. It is very common to find two people with the same income BUT with very different socio-economic environments behaving very differently as consumers.

For example: Television buying is more income-driven, but the programs watched are socio-economic class driven. Several computing products fall in this category, where income is not the best predictor of consumer behavior.14

14. Bijapurkar, Rama. 2008. We Are Like That Only. India: Penguin Books.

The future, in sum, will present us with quite the opposite of a homogenous world. Likewise, the profile of the “typical” global consumer will very soon be very different from those of the past. Without a “template” of this emerging consumer, understanding this new consumer ecosystem at the local level becomes essential.