Institutionalization of UX: A Step-by-Step Guide to a User Experience Practice, Second Edition (2014)

Part II. Setup

The Setup phase establishes the infrastructure needed to complete efficient and professional usability work. Certainly, you could hire some usability staff members and put them into project teams. But completing this phase marks the difference between a real institutionalization effort and unprofessional puttering. Without an effective strategy, training, methodology, facilities, tools, templates, and standards, a usability practitioner is unlikely to be successful and efficient.

In the Setup phase, you create a strategic plan that includes specifically sequenced steps, resources, and activities. This plan helps you build an infrastructure to support ongoing usability work. The infrastructure includes training for everyone, which provides an understanding of usability as well as specific skills for the design team. The organization also develops a user-centered design methodology, integrated with the general system development life cycle. A user-centered process recognizes the design of the user taskflows and experiences as the first priority.

You also create a set of reusable questionnaires and templates, decide which facilities and equipment you need, and develop interface design standards. The Setup phase is about building the infrastructure so that ongoing user-centered design can be completed in an efficient, repeatable, and professional manner.

Quite a few components and interactions are included in the Setup phase. The methodology must work with internal processes, and the standards must work with the technology and the business objectives. With all these complex elements to address, you can’t expect everything to work out smoothly the first time. That’s why the showcase project is strongly recommended—to work out the kinks in the process and prove that it all works.

Chapter 3. Institutionalization Strategy

![]() Create a strategic plan that has an overall roadmap and a detailed description of each activity, including objectives, activities, and deliverables.

Create a strategic plan that has an overall roadmap and a detailed description of each activity, including objectives, activities, and deliverables.

![]() Getting this plan right is critical. It is a very complex puzzle, specific to your situation.

Getting this plan right is critical. It is a very complex puzzle, specific to your situation.

![]() Select and sequence activities to optimize practicality, efficiency, and support for cultural change.

Select and sequence activities to optimize practicality, efficiency, and support for cultural change.

![]() You can bootstrap the usability effort. The benefits of the small early activities often can fund the larger tasks of establishing infrastructure and an internal team.

You can bootstrap the usability effort. The benefits of the small early activities often can fund the larger tasks of establishing infrastructure and an internal team.

![]() Let’s avoid these strategies that do not work.

Let’s avoid these strategies that do not work.

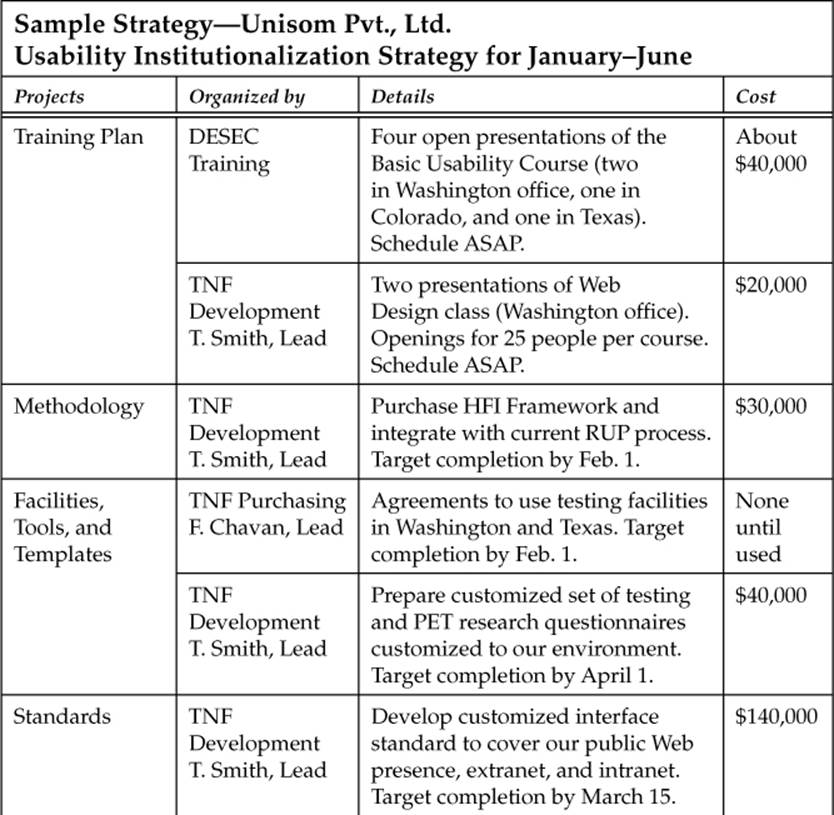

With all the excitement and pressure around user experience design, it can be difficult to take the time to strategize. But we have learned that the old saying, “Well begun is half done,” holds true with UX design. A strategy for the institutionalization of UX design will lay out the plan and ensure that every component of it happens at the right level of investment, with the right tuning of the deliverable, and the right timing (Figure 3-1).

Figure 3-1: Sample strategy for institutionalizing user experience design

Without question, the executive champion must outline and own a written strategy for setting up and maintaining the UX practice. Nevertheless, this executive will not be equipped to create the strategy alone. He or she may have insights into the range of possibilities for a user-centered design practice as well as the priorities of the organization, but an expert will be needed to help set up the program. That expert cannot just be a good user experience designer—you need someone familiar with the issues in setting up a practice.

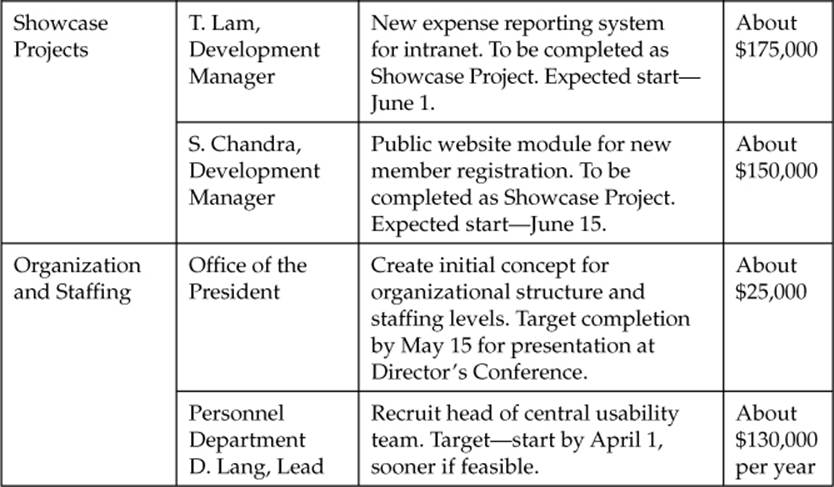

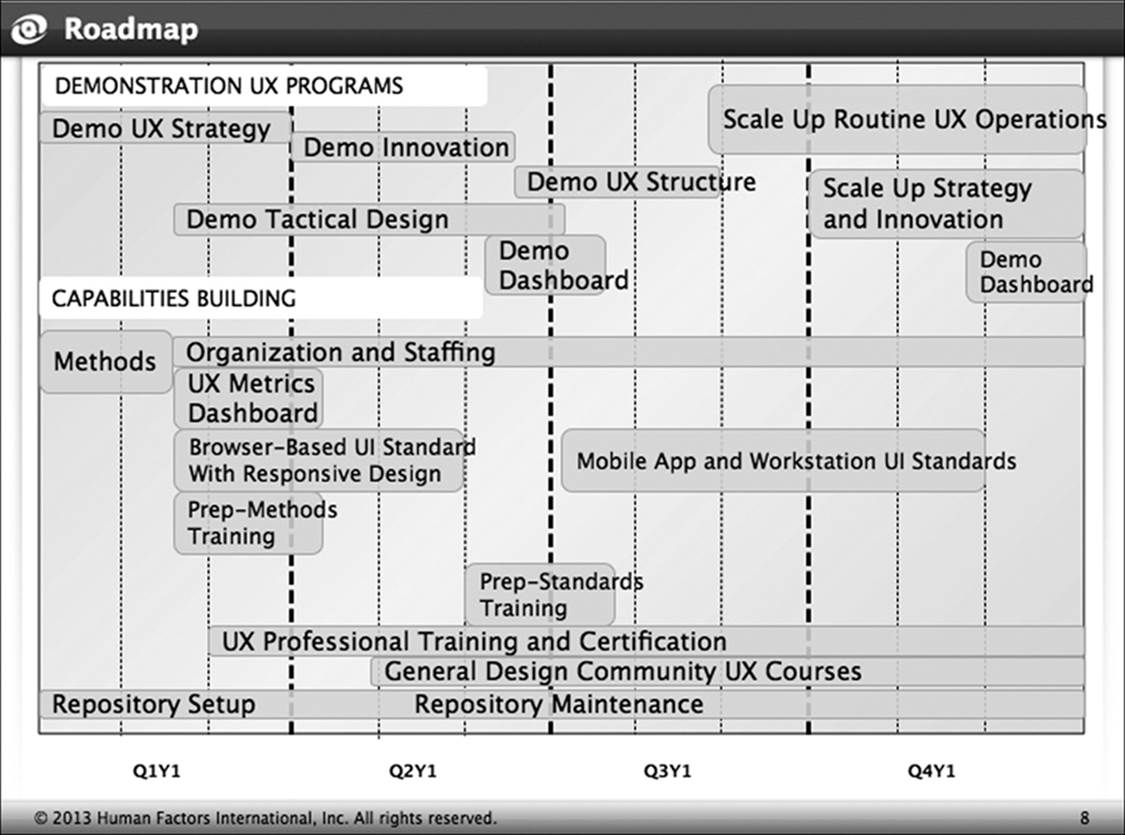

In some situations, you may be setting up a practice from scratch. More likely, you will be taking a limited internal capability and evolving it into a more mature, effective operation. In either case, there must be a roadmap that defines the specific activities needed (Figure 3-2). Each activity needs clear and detailed descriptions (Figure 3-3). It is not enough to say to your team, “We are going to develop a methodological standard”; instead, you need to document the exact focus of the standard.

Figure 3-2: Sample roadmaps for institutionalizing user experience design

Figure 3-3: Sample detailed write-up for institutionalizing user experience design

Creating a strategy could take a few weeks, or in a large complicated operation it might take several months. It is always necessary to have a good picture of the current user experience design capabilities (to identify gaps), the current design quality (to prove the value of improvements), and the organizational culture (as executive championship, governance, and organizational structure are likely to be key challenges). With this foundation, it is possible to create a list of work packages needed and then sequence these as a roadmap.

This chapter indicates some of the key considerations and tradeoffs to be aware of when carefully composing a strategy. No simple formula works in all environments, but it’s important to get your strategy right. A poor strategic plan can doom your institutionalization effort.

What to Consider When Developing the Strategic Plan

Putting a mature user experience design practice in place can be a lot like changing an airplane’s wings while it is in flight. There is a blizzard of current projects that have to be supported. At the same time, you need to put capabilities into place. While this situation might seem daunting, it is actually a good place to be (assuming you have the resources to avoid getting buried under the immediate tactical needs). Ideally, you can have a real synergy between tactical programs and building capabilities. Recognize that your tactical programs can serve as showcases through which the value of mature user experience design can be demonstrated. It is odd: you can show a dozen industry examples of the value of user experience design to executives, but they never seem to have the impact of a single internal project. It is particularly useful when you have some programs that try to get by without user experience design, and perhaps others that a marketing firm and perhaps some good visual designers have attempted to help make customer-centered. When these efforts are compared with serious user experience design, the results usually make a compelling case for UX institutionalization.

Concurrent showcase projects also have value beyond conveying the value of user experience design. They allow you to refine and validate the infrastructure created in your capabilities-building program. You can apply the methods and standards and see if they work smoothly in your environment, and verify whether your staff can really complete designated activities. In the end, then, it is a major benefit to have parallel tracks of tactical work and capabilities building.

While it may take two years to complete your overall institutionalization effort, you will see benefits from your tactical work almost immediately. Moreover, the growth in user experience design infrastructure will start to pay off within a few months. The documented plan itself can be a short-term program with a duration of as little as three months or as long as two years. In any event, there should always be a written strategy covering the current growth path of the user experience design operation.

Your strategy must identify the planned activities, time frame, resources, and responsible entities in your organization and should address the following questions:

• Which sequence of usability initiatives will work best? Although some steps must be completed before others, you have choices with some of the sequence decisions you make.

• Have you considered your environment? How will your organizational culture affect the way you implement your user experience design practice?

• What are your most pressing projects, concerns, and objectives? As you begin the process of institutionalizing user experience design, you can have it unfold in a way that meets your most important issues.

• Are there people or units that particularly need to get on board? Pockets of resistance exist in every organization. Identifying yours and building them into your strategic plan is critical.

The strategy essentially describes who will be responsible in your organization and what they will be doing. This concept seems simple, but the decisions you make have significant implications. The following sections cover the main considerations involved in selecting the who and what for your strategy. Your usability consultant may be able to help you think about these issues and develop the best strategy for your environment.

A Proactive Organization

As you start the institutionalization effort, it is essential to set up a proactive effort. It is easy to start putting out the numerous fires of poor usability and have a small dedicated staff work to fix the tidal wave of bad designs, one by one. Be forewarned—this approach is guaranteed to fail. It is like having doctors administer to all the health needs of the community, from taking temperatures and applying bandages to transporting patients and performing surgery. The medical community can’t work that way, and neither can your user experience design staff.

The medical community has paramedics, nurses, and physician assistants to help with the range of its activities. For your company’s strategy, you need to build a similar set of facilities to create a pro-active organization. This is the only way to ensure routine usability.

Coordinating Internal Staff and Consultants

In Chapter 2, we described why your organization should consider using an outside usability consultant and how to choose one. Even with all the value that a consultant can bring to an organization, however, internal staff remain invaluable. Using internal staff costs less than hiring local consultants, to be sure—but there are far more advantages related to this decision than simply the cost. Internal staff members are the only people able to focus fully on business content and strategy within the company. They can learn the subject matter deeply, or they may already know it. As a consequence, they can be more efficient in design work. They can also develop a set of instruments and procedures that really fit perfectly with the issues the company faces. For example, if your organization is in the medical field, staff members will be aware of the latest FDA requirements. If your organization is in customer service, the staff will know the history of issues with workstation and voice response system integration. They know from first-hand experience what to attend to in the next release. Having the greatest familiarity with your customers, internal staff members can focus on building a shared model of the customers’ ecosystem.

The global best practice for user experience design is to have it done primarily by an internal group, possibly with the supplemental support of vendors. Hiring a set of disparate vendors ensures a hodgepodge of incompatible, misaligned results.

Internal staff members also have an advantage when it comes to UX design institutionalization because they work in the organization on a long-term basis. They have established relationships with employees and groups within the company that are not involved in usability. Perhaps most importantly, they know the opinion leaders and sources of power in the organization, so they can often achieve a level of consensus and buy-in that consultants can’t match. Internal staff also hold you accountable to your user experience design goals: while it is all too easy to tell a consultant, “Yes, we will accomplish user-centered design now,” and then ignore the issue the next week after the consultant has gone, the internal group is in a position to deeply embed the usability perspective into the organization over the long term.

It is possible to have supplemental support from vendors. Organizations vary a great deal, so it is vital that your strategy fits your company culture. For example, some companies may be accustomed to having consultants work closely but independently, while others may want a consultant to just coach staff briefly or may prefer to do all the work with in-house staff. In every modality, however, there must be a strong internal user experience design group that maintains standards, methods, a persistent knowledge base, and strong quality assurance.

The Importance of Sequence

This book presents phases and activities for institutionalizing usability. Most companies modify this process somewhat. As you develop your own strategy, be sure to consider the sequence of activities that will make the most sense for your environment.

Consultant and Internal Group Mix

Todd Gross, Ph.D., former Director—Corporate Statistics and Human Factors, Medtronic MiniMed

At Medtronic MiniMed, we used a mix of in-house and outside resources to complete our human factors projects. Outside consulting offered several benefits. Consultants could focus exclusively on our projects, whereas in-house personnel were often faced with multiple competing priorities. Consulting firms also offered greater depth of resources and expertise to dedicate to a project. This allowed them to complete the projects more quickly and with more comprehensive output than in-house staff can generate.

Another benefit of outside consultants is that they brought a fresh perspective to a project. Their experience with a broad range of products and applications allowed them to present recommendations in a way that was valuable. There’s something about hearing opinions from an outside entity—the good news sounds better and the bad news has greater credibility than when in-house personnel present it. It’s sort of like if a date tells you that you dress funny, you might give that greater credence than if your mother tells you the same thing.

In my experience, this mixture of outside consultants and internal staff can produce a powerful alliance to promote the use of human factors knowledge throughout the organization. I like the idea of having a department that provides core resources—I think that, on a long-range basis, manufacturers need to have that internal core. But the in-house staff can be complemented by a strong consulting relationship, especially for a company like Medtronic MiniMed, which makes devices with a broad range of human factors issues. Some of the devices are purely mechanical and others are electronic, with both hardware and software interface issues. This product diversity requires a corresponding wide range of human factors approaches in both design and evaluation. In addition, the FDA has continued to champion, and even mandate, the use of human factors during product development and usability testing. Knowledgeable consultants can supplement internal staff’s experience with these regulatory requirements.

It is truly exciting to see the dynamic that can develop between internal and external team members, with in-house content experts providing the raw material, in the form of product-line knowledge and development history, and consultants helping tweak both product design and usability evaluation plans, combining to create a cohesive and effective strategy.

Many logical connections are built into the institutionalization methodology described in this book. For instance, keep the following sequences in mind:

• Have your strategy in place before the infrastructure setup begins; otherwise, you will spend money in an inefficient and uncoordinated way.

• Have standards in place before starting projects; otherwise, you will create a larger installed base of noncompliant designs.

• Get the upfront design process working before doing usability testing so that testing can fine-tune reasonable designs instead of documenting designs that are not even close to correct.

• Finalize your methodology and organizational design before you start the hiring process so you can be sure to hire user-centered design staff with the right skills and abilities.

These interdependencies are important and should always be considered when planning your strategy. It is also important to use the sequence to maintain flexibility. As in a chess game, it is unwise to move in a way that unnecessarily closes off options.

To demonstrate the value of considering sequence, let’s consider when to hire usability staff. It’s often better to delay full-scale hiring of usability staff until you have a formal methodology documented and the work within that organization allocated within the organization. You might find that with mentoring and oversight, trained business analysts can handle detailed design. This approach leads to a very different staffing requirement than large-scale hiring.

Reacting to Past Events

Many organizations have had bad experiences with consultants, making it difficult for them to work with a usability consultant. The new consultant may say that he or she is different—but then the previous consultant may have made the same claim.

If you have a negative history with outside consultants, it is critical to go about the relationship-building process more slowly. You may need to start with very small projects. Take time to gain trust and put the bad experience well in the past. The staff may also need much more explanation about the consultant’s conclusions. There is never a time when people should take user experience design recommendations on trust—they should always be given the full rationale and research data behind each recommendation. Allow extra time for this.

Another past event that should trigger reflection is a difficult wake-up call for the organization when a design failed. This otherwise negative experience can be a resource that provides momentum for change in the organization. However, such challenges can also create too much drive. Overall, it is best to avoid strategies that are driven by a sense of panic. They rarely work well in the long term. If you are reacting to a wake-up call, avoid taking on lots of projects. Instead, select a few key programs and make sure they are completed successfully.

Targets of Opportunity

The greatest drivers for differences in strategy are existing tactical opportunities. It is important to establish a plan and shift the sequence of institutionalization to take advantage of the organization’s current activities.

You might find that you can get training in conjunction with another company in your area, so training might be moved to meet this schedule.

You might find that you are installing a revised system development methodology. This is a great time to add a user-centered process to supplement the new method, instead of having staff members learn the system-centered method first and then learn about user-centered design separately.

You might select a showcase project because it is visible, or because the staff members are very interested in usability, or because the project is small and manageable and needs to start at the right time for the usability initiative.

Perhaps you have an opportunity to hire a very skilled usability specialist who is a good fit for your culture. Usability staff with skills and compatibility are very hard to find and may be on the market only for days. If unique opportunities are present, mold your strategy to hire sooner.

Clearly, as you establish your strategy, you must shape it to your opportunities and also expect some fine-tuning to occur as new opportunities arise.

Slower Can Be Better

Achieving a successful institutionalization program requires time and patience. There is an uncomfortable joke in aviation that captures this principle quite well. A plane called the “V-Tailed Doctor Killer” has a funny tail design, but is nonetheless a powerful and complicated aircraft. Many doctors have the money to buy such a machine, but they do not have the time or experience to use it safely. They can fly the plane under normal and comfortable circumstances, but in more dangerous and pressure-filled moments, they lose control.

It is much the same with a user experience design practice. You can buy a complete user experience design infrastructure. You can implement training, methodology, standards, tools, projects, and hiring. It takes a great deal of effort and money to put these elements in place, but until the organization has had time to fully digest each intervention and each component of the infrastructure, there is little value in it. It is all too easy to bite off too much and then think you are well fed. Take your time in implementing usability, and build that time into your strategy.

Phasing in Design Standards

In your strategic plan, make sure you get interface design standards in place early. Good design standards are so valuable that they can be justified almost anytime there will be significant and ongoing development. Standards save development time—and there is a real increase in expenses when developers must spend time reinventing the wheel. When there are no standards, it is as though you can hear a clock ticking. Also, developers do not have the time, skill, or attention to dedicate to creating a design that a standards team has. Therefore, developers’ designs are almost certain to be suboptimal.

The biggest concern, however, is that current projects completed without standards will lead to a growing set of noncompliant screens. These screens must then be modified to bring them into compliance. This is a daunting task, and no company ever seems to do it all at once. Instead, noncompliant designs are grandfathered in. They are brought into compliance with the standard only when they are being revised as part of some renovation or enhancement program. This makes the conversion less daunting and spreads the cost over years. While this tactic might seem like the rational thing to do, it is quite costly to let developers keep churning out nonstandard designs while you delay standards development.

Aside from the costs of eventually converting the designs, working with a committee that represents an installed base of noncompliant and diverse designs can create a psychological drag on the process of creating standards. You can see each committee member judging the concepts based on how closely they match his or her own designs or the designs of his or her department. These committee members cannot see the ergonomic quality of the new, standards-based designs, and they cannot interpret the value of the new design to the company; instead, they are simply entrenched in defending their past decisions.

These groups can be hard to work with. You end up painstakingly having to take apart those past designs one by one. Typically, you have to show the ergonomic problems with the old designs, and the people involved must go through the process of accepting that they created an imperfect design and realizing that their designs need changes.

Providing a training class for the committee members leads to an infinitely smoother process. With training, they can see the problems with their designs themselves. Nevertheless, the larger the installed base, the more staff members have a vested attachment to the designs, and the more visceral resistance to making changes they are likely to demonstrate. Of course, you should avoid making unnecessary changes in past design conventions. Recognize, however, that people can develop powerful arguments for retaining very poor designs.

Key Groups for Support or Resistance

The institutionalization of user experience requires a set of discrete activities and resources, but the key to success does not lie in these accomplishments, but rather in the understanding and beliefs of the people within the organization. It is not unusual for companies to spend six figures on a usability testing lab, only to see it sit unused. Without the acceptance of user experience as a focus of concern by the people in the organization, there will be no real success.

The people in your organization can be classified into a number of key groups from the viewpoint of institutionalization. First, there are the early adopters, easily excited about usability, who almost instantly grasp the concept, methods, principles, process, and value of user experience. The earliest stages of the institutionalization effort need to focus on identifying these people and getting them on board. They will provide early momentum. As time goes on, you will need to worry about keeping them motivated and preventing them from feeling too frustrated with the pace of the overall organization. If they become bitter, they will alienate others, so keep them seeing successes.

A second key group is the power structure within the company. In a sense, the progress of institutionalization is wholly reflected in this group’s level of understanding and appreciation. As user-centered design becomes a given from the perspective of the executive suite, impediments will melt, resources will appear, and success will be assured. If the executives are indifferent, long-term success is essentially impossible. Reaching these players is key. Put effort into including them in the design process (as experts in strategic direction and brainstorming), communicating successes, and providing education. You do not need these leaders to do the design work, but they should help you work on the organization’s process of design.

When executives get involved in design, they follow several patterns. Some may attempt to micromanage the entire process or single-handedly reinvent the entire human engineering profession and literature. Others may drop into the design process periodically and make recommendations. This can be quite detrimental, but the worst situation is the executive who hands down design edicts from on high. These executives are the people who want to see “a big red area at the top” or “a tree view at the left.”

These executives are usually so powerful that the design team feels forced to follow their orders precisely, rarely with a positive impact. Such executives become an all-powerful design constraint—and the design team already has enough constraints. Executives need to reinforce the need for user-centered design and the value of optimizing user experience, performance, and design consistency, but they should never specify a design feature. Even with great experience and training, it is quite difficult for a consultant to select any substantive design decision that can be mandated in every situation, so executives should certainly not attempt to do so.

Executive Support for Usability within AT&T

Feliça Selenko, Former Principal Technical Staff Member, AT&T

In an employee message to the people of AT&T, Dave Dorman, AT&T CEO, states, “AT&T has an important initiative under way to dramatically improve our ‘customer lifecycle’ processes. The intent of this effort is to drive higher levels of customer satisfaction and retention, and differentiate AT&T from the rest of our industry. By removing errors and the resulting rework, we reduce cycle time, improve customer satisfaction, and reduce our costs of doing business.” That sentiment is reflected in every set of executive goals and objectives I have seen this year—that is, optimizing the customer experience is always one of the most important goals/objectives.

Although AT&T executives are using the term customer experience, which is broader than usability, goals/objectives focusing on the automation of manual processes, optimizing the customer’s self-serve experience via easy-to-use Web tools, and removing errors from processes and interactions to reduce rework and improve cycle times are all aspects of the customer experience impacted by usability engineering.

A third important group is the people who are against usability, or the “naysayers.” It might seem odd to think that there could possibly be people like this in the modern-day business world, but there are. Down deep, they do not want to lose control of the design process. They want to continue to enjoy designing things they like, without needing to validate that the users can understand, use, or appreciate the result. There is a joyful freedom gained just from creating elegant code, while there is an unpleasant messiness to meeting the inconsistent, ambiguous needs of users. Naysayers won’t admit to this type of thinking, but it is often what really drives their criticism.

Naysayers can come from different groups. Marketing staff members might think things will go well if they make sites that wiggle and dazzle users (although users often consider such sites “sales-y” and disreputable). Graphic artists might want to concentrate almost wholly on the beauty of the design and not worry about whether it can be navigated and operated easily. Systems coders might want to use the easiest technological route or perhaps the latest and coolest technological innovation.

Rather than seeing the benefit of referring to user needs and limitations as they create a design, naysayers will suggest that systematic user-centered design “takes too much time.” Expect them to question the ROI of usability work. (In response, you might ask them if they have ever seen an ROI calculation for having a database designed by professionals instead of by amateurs.) Naysayers may suggest that, because their design intuition is so good, they can create better user interfaces than the ones based on ergonomic principles and user-centered design. Users will certainly like their designs more, these folks will claim. They will suggest that good usability cannot be achieved within technical constraints. If you point out problems in past designs, they will often reference past technical constraints that were recently solved by new technology.

Your strategy must eventually address these naysayers. They will listen to proclamations about user experience by executives, but think and act as if it is just the management buzzword of the month. (After paying it lip service, they will try to forget it.) They will pay some attention to presentations demonstrating the value of usability in pilot projects, and take more interest in presentations that include testimonials from other naysayers saying they saw value and practicality in the user-centered design process.

But one strategy works best. Most of these naysayers will be problem-solvers by nature. They will love to solve the most complex development challenges, and they will feel effective when they can break through these challenges and succeed. A breakthrough is possible when these people are tasked with finding a way to meet a customer need; they will find that usability is fun, and that it offers them a whole new set of puzzles to solve. No amount of ROI calculation or explanation will match that thrill.

The final key group comprises the masses in the development community—the mainstream developers. Once a strong core group is established to support usability, the members of that core group must begin the process of evangelizing and mentoring other developers. This effort will take some time because there are many mainstream developers, and they change slowly. Nevertheless, institutionalization is established only when this mass of developers has been reached. They will be swept up in new projects that apply user experience design practices. In addition, they will benefit from training and presentations. The mass of developers can also be reached by a set of online methods and tools presented on a company’s intranet. Finally, consider including user experience as a part of your training program.

Training

While training is not a magic pill, it is a major pillar of the institutionalization effort. You may need several levels of training—for more information, see Chapter 8. Training provides widespread awareness of usability issues and instills a crucial element of motivation in the early stages of institutionalization. It can also be used to educate executives and evangelize the value of user experience.

Training provides skills for developers who must participate in user-centered design. It is true that the fine points of usability engineering seem to be best shared by mentoring, but without training in the basics, the mentoring process is long and frustrating. Skills-level training is really required.

Methodology and Infrastructure

It is common to see companies hire a few usability people and toss them into the design environment. It is like deciding that you want to have metal weapons and hiring a few metal workers. Certainly, they can set up a few huts with hand-driven furnaces and can begin work with a hammer and anvil. But if you want both efficiency and quality, you need to build a modern factory—then when you toss the metal workers into the factory, you can expect good results.

Without a user-centered design methodology, the development team members will end up working tactically. They will think of some of the right things to do, and they will have a positive impact, but a systematic approach will be more thorough and more efficient. For this reason, it makes sense to fit a user-centered process to your current development life cycle. Do this early, because time spent without a structured process is likely to be inefficient.

Once you’ve chosen a methodology, you can move toward establishing a toolkit that supports the methodology. Facilities, tools, and templates make work on the user experience design engineering process even more efficient. These “modern machines” lead to quality and efficiency. Chapter 4 provides more information on methodology, while Chapter 7 provides details on facilities, tools, and templates.

The Project Path

Selecting the showcase projects to work on first is one of the biggest decisions in the strategic plan. Obviously, you must select a project that is just starting so you can demonstrate the whole process. You should also select a project of manageable size and duration. It helps little to tackle a showcase project that won’t be completed for many years.

It is equally important that the showcase project have significant user experience design objectives. Find a project with lots of users to whom user experience and performance is important. Chapter 13 covers in detail what to look for when selecting a showcase project.

Levels of Investment

User experience institutionalization, infrastructure, projects, and staffing are not free. It costs less in the long run to complete designs with the right methods and tools, but in the short run, an investment is required. It is valuable to calculate the ROI for implementing usability within your organization. Know the specific ways that user experience design will pay off.

The investment in user experience can be staged and progressive. For example, in my experience, the investment in an expert review or usability test will be in the range of $35,000 to 70,000 and can motivate managers to get serious about user experience design. The cost of the initial setup of a usability program for a large company by a consultant is typically about $800,000 to $1.5 million. The cost of establishing a UX design group and supporting it might be $1 million to $5 million annually.1 Clearly, then, starting a usability program is a progressive process: each step should instill the confidence to go ahead with the next level of investment, and each step should fund the next.

1. This figure, along with the others in this paragraph, is based on HFI’s 20 years of experience with hundreds of clients across thousands of user-centered design projects.

Summary

Your attempts to make customer-centered design become routine will require significant changes throughout your company. A practical, high-level strategy will create the organization necessary to bring your decision making to the next level. This is the transition from a piecemeal and immature usability capability to a mature and well-managed process. The next chapter provides more details about the training element of your strategy.